History

Good Gun Tales

Bass Lecture: Good Gun Tales and the 73-Year History of the Bowdoin Scientific Station on Kent Island

A rich past

But long before that moment, Maine’s Passamaquoddy Indians had used Grand Manan, Kent Island, and other nearby islands as a summertime base to hunt porpoises and seals. They also harvested sweetgrass to weave into baskets when they returned to the mainland. Passamaquoddy people continued their yearly visits to the islands until 1930.

Each summer, the islands attracted huge colonies of nesting seabirds—herring gulls, guillemots, Leach’s storm-petrels, and great black-backed gulls. Native people had hunted these birds for many centuries, managing to sustain their populations. Yet, by the early twentieth century, the new human arrivals to North America had zealously over-hunted the eider duck for meat and over-collected its eggs and feathers, leading to a near collapse of the population.

The plundering of the island’s eiders began in earnest after its first white settlers, John Kent and his wife, had both died. After settling his family on the island in the late 1790s, John passed away in 1828. Susannah, who was said to be a witch, lived for many more years alone in their island farmhouse. Her spooky reputation protected the island’s birds, though, as locals were said to be too frightened to come near her.

But after she died in 1853, it did not take long for hunters to reduce the vast population of eiders to just a handful. Allan Moses (1881-1953), a naturalist who lived on Grand Manan, watched the situation with grave concern.

The arrival of the albatross

Moses was an expert taxidermist, and he kept a small private museum on Grand Manan. His specialty was birds, and so was delighted when his friend Ernest Joy in 1913 presented him with the carcass of a rare yellow-nosed albatross that Joy had shot after spotting it flying near Machias Seal Island.

There had been only one previous reporting of a yellow-nosed albatross in North America, and the specimen became Moses’s most prized object. In 1919, an ornithologist from the American Museum of Natural History, on a visit to Grand Manan, took note of the stuffed bird and offered to buy it. Instead of selling, Moses—who dreamed of traveling the world—negotiated with the museum to allow him to join one of its collecting expeditions to central Africa.

Expedition leader J. Sterling Rockefeller's mission was to collect birds for the museum, with the ultimate goal of bringing back a small, rare flycatcher called the African green broadbill. Yet, after many days scouring the jungle, he and his team did not see one, and so turned their attention to tracking other species.

When Moses came down with malaria, he was bitterly disappointed to not be able to join the exciting daily outings. Yet, it was on one of these days of rest when Moses happened to spot the broadbill near his tent—and acted quickly to shoot it. Rockefeller was so grateful, he asked Moses how he could reward him; Moses requested help with his dream of preserving Kent Island.

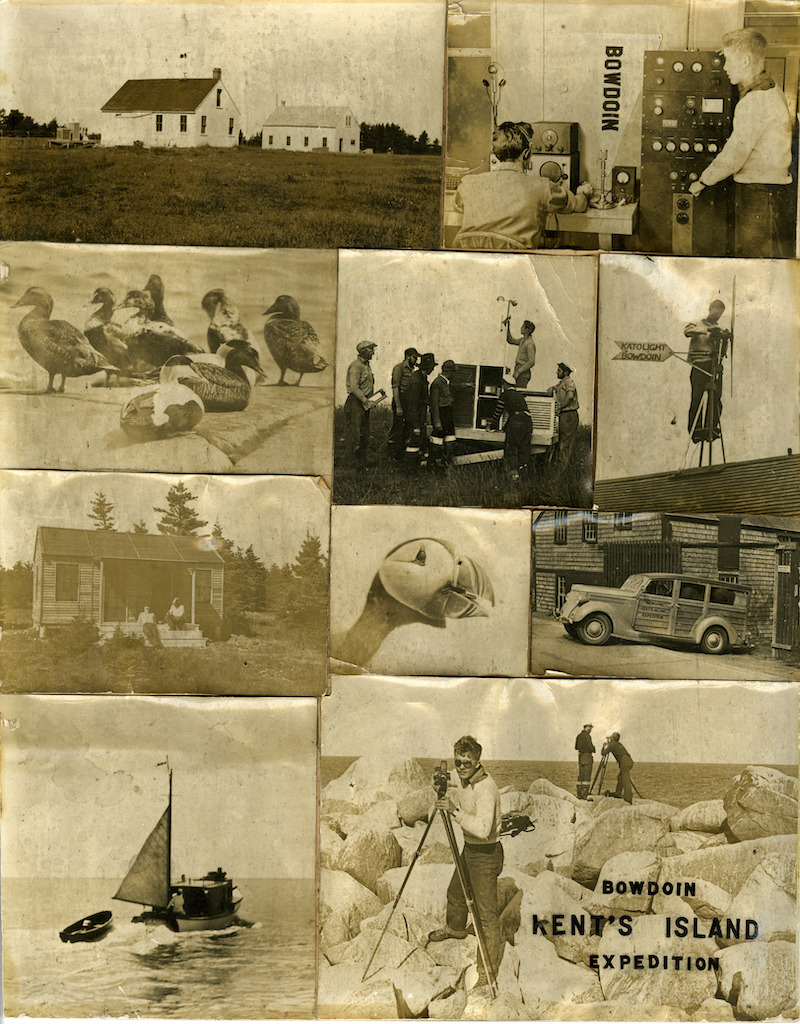

So Rockefeller bought the island in 1930 for $25,000, established a bird sanctuary, and allowed Alfred O. Gross (1883-1970), a biology professor at Bowdoin, to begin a study of its eiders. Gross organized the first research season with students on the island in the summer of 1935, and in 1936, Rockefeller donated the island to Bowdoin. The Bowdoin Scientific Station was founded soon after. Fittingly, the College hired Ernest Joy as its first island caretaker.

Since then, the eider population and other nesting bird colonies have recovered. But climate change and over-fishing are now threatening the future of many pelagic birds, including those who return to Kent Island year after year.

Bibliography

Keith Ingersoll's book, Wings Over the Sea, details the founding of the Bowdoin Scientific Station in 1934, while Frank Graham's Natural History article gives an abridged version. Perhaps the most personal history comes from correspondence between the Bowdoin Scientific Station's first caretaker, Ernest Joy, and Bob Cunningham, who began his studies in meteorology at Kent Island as a teenager in the late 1930s. Some of those letters are available on this site; the full set, in Ernest's hand, are available through the Grand Manan Museum.

Kent Island’s history is inextricably linked to the history of neighboring island Grand Manan. In 2015, Bates College student Kate McNally spent the summer on Grand Manan exploring and chronicling the island’s history, culminating in the book, Forethought and Labor: Oral Histories from the Island of Grand Manan.

Other good reads are Grand Manan, by Eric Allaby, and Tides of Change on Grand Manan Island: Culture and Belonging in a Fishing Community, by Joan Marshall. Lastly, Peter Cunningham, son of Kent Island meteorologist Bob Cunningham, has organized some of his amazing photography into a book of stories about Grand Manan called Fogseekers: Dwelling in the Heart of Not Knowing.