Down in the Dirt

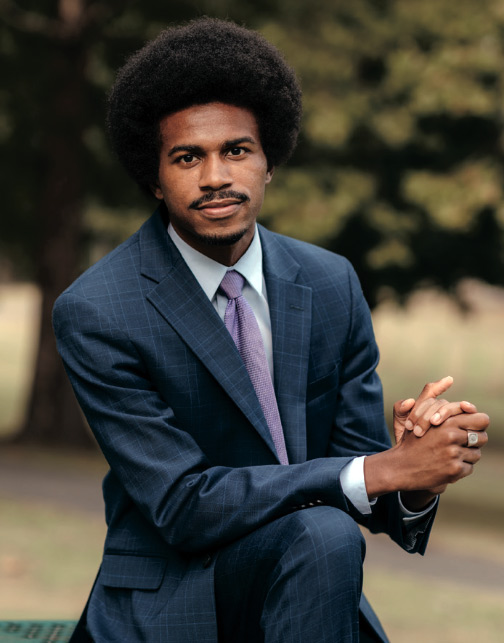

By Oliver Goodrich for Bowdoin MagazineBowdoin’s director of religious and spiritual life, Oliver Goodrich, recalls the dirty and humbling experience of picking potatoes that helped him understand his place in the world and the idea that humility is the gateway leading to understanding ourselves and others.

Driving north on Maine’s Interstate-95, miles before you reach my hometown of Houlton, you’ll begin to notice potato fields carved among the rolling hills. Potato farming is an Aroostook County tradition that goes back generations. Many small towns hold festivals each year in July to celebrate fields full of tiny white flowers, and whole communities roll up their sleeves to harvest the crop each fall.

As a child, I heard stories from my mother and grandmother about the hard work and adventures of the harvest. My grandmother would boast of picking 120 barrels of potatoes a day, a feat she had accomplished with a child hanging off each hip. My mother could pick eighty to a hundred barrels a day—not quite up to her mother’s standards, but impressive. When I finally got my first experience picking potatoes in 1997, my largest haul was a meager forty barrels. Most days less.

Potato picking was hard work. I was a young man at the peak of my teenage fitness that fall, but I would arrive home at the end of the day barely able to stand up straight. My aches earned no sympathy with my family. My mother insisted that I head straight to the bathroom to wash the soil off my skin and out of my hair. My jeans were so caked with dirt that they would stand upright on their own.

Despite the back-breaking work—and the fact that my grandmother never forgave me for tarnishing our family’s potato-picking reputation—I grew to love the potato harvest. I loved the time in the hills and fields, abundant with birdsong and clear sky. I had a front-row seat to the magic of Maine’s changing fall foliage. More than anything, I keenly felt I was a part of something. I had heard talk about the potato harvest tradition my entire life, but it wasn’t until I rolled up my sleeves and got down in the dirt that I really understood.

My great-uncle Linn Phelan was a potter who ran a small but successful studio in the Finger Lakes for over forty years, producing an average of a thousand ceramic pieces a year. One summer, when my younger sister and I were in grade school, we visited Uncle Linn’s studio. We loved getting our hands wet and muddy on the pottery wheel, and we watched with fascination as Linn showed us how he painted and then fired his work in the kiln. Our favorite part of the visit, however, happened outside.

Linn grabbed a stack of ceramic plates from a table and led us out to his driveway. Looking down, he asked, “Notice anything special about the gravel?” We studied the driveway, then my sister asked, “What are those? They look like broken pieces of pottery.”

“That’s exactly what they are!” Linn exclaimed.

“Did someone break in and destroy your work?” I asked.

He laughed. “No, I broke them…like this!” He threw a plate at the driveway, shattering it to pieces. My sister and I froze. We stood there stunned until Linn started laughing. Even after all his years as a potter, he said, he still made mistakes. Rather than waste his work, he thought it fitting to return it to its metaphorical source.

He handed us each a small stack of plates. We laughed and danced as we smashed them into his driveway, overjoyed that for one of the first times in our young lives, a grown-up not only admitted mistakes but also celebrated them.

Like many who grew up in religious spaces, I had a vague sense that humility was the opposite of pride and a corresponding fear of overconfidence. Perhaps that’s why, as a college freshman, I was convinced I was the least intelligent person on my campus. I distinctly remember the nerves I felt as I prepared for my very first lecture on my first day, certain I was about to be found out for the intellectual fraud I feared I was.

That first class was an introduction to the Hebrew Bible, and as though he could read my mind, my professor opened his lecture by offering a few words of advice. “I know many of you here today are new students, and I can imagine that you are feeling some nerves about beginning college,” he began. “If I may, I’d like to offer you some advice. If you came to college in search of wisdom, the Hebrew Bible is a very good place to find it. The scriptures exhort us to hold two truths in balance if you want to gain wisdom: on the one hand, you must have the humility to believe that you have something to learn, and on the other hand, you must have the courage to believe that you can indeed learn.”

My professor’s advice cut straight through the fog of my fear and invited me to combine humble self-assessment with courage that reminded me that I was indeed capable of learning. It also was the first time that my emerging adult self had considered the possibility that humility wasn’t only a religious commandment. If my professor was right, there was wisdom for all humanity in humility.

Religion has a lot to offer on the topic of humility, which is lauded as a virtue in nearly every major religious tradition. Over the course of my spiritual journey, I spent time worshipping in the high church traditions of Anglicanism and Catholicism.

In both traditions, humility comes up like clockwork on Ash Wednesday, which marks the beginning of Lent and the period of preparation for Easter. When I would receive ashes on my forehead, I was told, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

The word “humility” derives from the Latin root humus, which can mean soil, dirt, dust, or earth. It turns out there is another common English word that linguists believe share the same root: human. This linguistic link helps connect the concept of humility with our human mortality and finitude; our lives are bookended by humus, and there is wisdom in remembering our humble origin and destination.

Our lives are bookended by humus, and there is wisdom in remembering our humble origin and destination.

On this point, it’s worth noting that science would seem to be in agreement. Viewing a photograph of Earth taken by Voyager I from 4 billion miles away, astronomer Carl Sagan described feeling humbled by the tiny “pale blue dot,” which, despite being the home of every human being who has ever lived, was barely visible against the vast backdrop of space. So far as I know, Sagan attached no religious meaning to this insight; even so, it carried a sense of social responsibility. Sagan wrote, “There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

Why is humility worthy of our consideration? Humility is a gateway to understanding both ourselves and others. Social psychologists have found that Americans are inclined to overestimate their knowledge and abilities. When we put humility into practice, we assess ourselves and our capabilities more honestly, acknowledge both our strengths and our limitations, and come to a more accurate self-understanding. Humility allows us to admit our mistakes, learn from them, and even celebrate them.

Not only does the practice of humility create a more accurate self-understanding, but it also makes space for us to see others more accurately and to better understand their experiences and perspectives. In a globally interconnected world, humility allows us to engage with others—from different cultures, countries, or creeds—and admit that our way of being is not the only way of being human. It wasn’t until I got down in the dirt of my hometown potato fields that I really understood the culture and tradition of Maine potato growing; doing so was dirty and humbling—and it helped me better understand myself, my community, and my place in it.

It makes me wonder: in this cultural moment we are living through, fraught with disconnection and divisiveness, what would happen if more of us adopted a practice of humility? Would it help ground our common life together in compassion and understanding? Could it help us feel more connected to ourselves and one another? Would we feel less afraid to make mistakes and more willing to extend forgiveness?

The choice to practice humility is courageous. It requires hard work, patience, and discipline. But perhaps, in this effort, we might discover that humility is more a part of our human nature than we had previously understood.

This is one in a series of four essays about humility, published in Bowdoin Magazine.

Oliver Goodrich is director of Bowdoin’s Rachel Lord Center for Religious and Spiritual Life. He is an avid runner, bird watcher, and fan of RuPaul’s Drag Race.

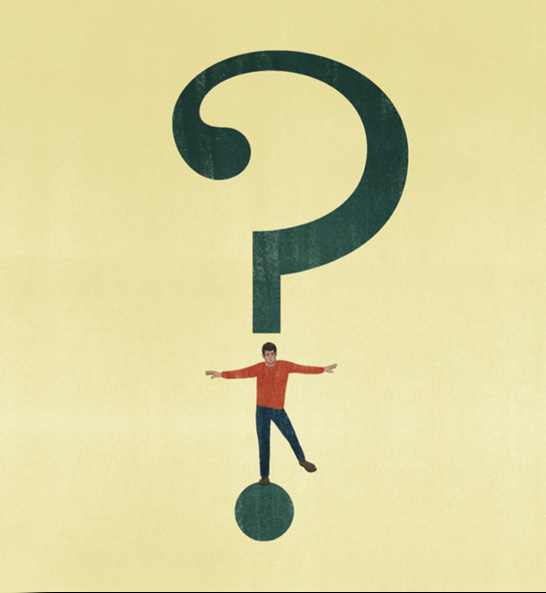

Francesco Ciccolella is an illustrator, graphic artist, and visual storyteller based in Vienna, Austria. His work has been featured in many publications, including The New York Times and The New Yorker. See more of his art at francescociccolella.com.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.