A Rightful Pride

By Barbara Held for Bowdoin MagazinePsychology professor Barbara Held writes about the thin line between humility and self-deprecation and argues that the virtuous golden mean of “truthfulness” is a better way to see humility.

Being asked to write an essay about humility took me aback. After all, I’m known for my moments of shameless self-promotion, about which I am—well—shameless.

Bowdoin alumni who were my students in the early two-thousands might be amused to recall one particular exchange I had with them regularly.

As students increasingly addressed professors by their first names, some of my students asked if they could call me “Barbara.” Preferring to be called “Professor Held,” I gave them a cheeky alternative, saying this:

“You may call me ‘The Precious Bundle,’” I offered. (Historical note: Tired of people our age asking my husband and me when we’d have children, which we had decided against from the start, I typically responded by saying, “I don’t need to produce a precious bundle, because I am The Precious Bundle.” That usually stopped them dead in their tracks.)

My students said they wanted to be “The Precious Bundle,” too. I told them that wasn’t possible because there’s only one precious bundle—me; hence the definite article “the.” But, not wanting to be too much of a party pooper, I offered them this option, saying, “You can all be ‘Special Bundles.’ And if you work hard, someday, when I’m gone, maybe one of you will be ‘The Precious Bundle.’” How’s that for shameless self-promotion!

Now, onto humility. It goes without saying that most see humility as a virtue. In his poem “Psychomachia,” the early fifth-century AD poet Prudentius represented Christian morality as a struggle between seven sins and seven virtues. He opposed the virtue of humility with the vice of pride.

My Protestant-raised husband was taught to adhere strictly to the proverb “Pride goeth before a fall.” He took it too much to heart, in my opinion. A man of many talents, he sometimes sold himself short.

I saw this same self-deprecating attitude in many of my Bowdoin women students, who had difficulty taking credit for their talents. You would think my shameless self-promotion would have provided a role model for women seeking to advance themselves in the world. But apparently not. They thought my shamelessness was a joke, but like many of my seemingjokes, I was only half-joking. By contrast, when I described myself with fake modesty as a “simple country psychologist,” which, as a Bronxite, was ludicrous, I was joking completely. Unfortunately, whereas my shameless selfpromotion wasn’t emulated, students expressed undue real modesty.

When it comes to humility, I prefer Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, in which he presents the virtuous “golden mean”—or middle ground— between each of twelve pairs of vices defined by an extreme of deficiency and of excess.

For the category “self-expression,” the vicious deficiency is “understatement/mock modesty,” and the vicious excess is “boastfulness.”

The virtuous golden mean between these two is “truthfulness,” which I find just right.

Where’s the shame in being straightforwardly honest about your talents? I have a friend who says, “Oh, stop it,” when I compliment her on some accomplishment. She says I’m embarrassing her by complimenting her. Why? Does she think she doesn’t deserve to be complimented? Does she think it’s too prideful to accept the compliment? This makes me feel bad for complimenting her. Where’s the virtue in that?

My advice is this: If you get complimented, just say, “Thank you.” Isn’t that a form of humility? And if you don’t think you deserve a particular compliment, you might ask yourself why not. Are you being too humble? Or is your complimenter buttering you up? I have a friend who constantly compliments me on everything he can think of, which makes me wonder how genuine he’s being. His compliments come across as flattery, which carries the negative connotation of seeking to influence others with insincere praise. That makes me a bit nauseous at times.

Then again, there are people who believe they are the best at things they aren’t (you can think of some people, I’m sure). They certainly could use some humility. Though, given their evident narcissism, it might be foolish, even for a psychologist, to try to get them to see their self-deception—their unwarranted self-confidence.

To be sure, the situation you’re in at the moment helps determine just what amount of humility, if any, is called for. In a job interview or when writing a college admission essay, you shouldn’t downplay your talents. But you also shouldn’t proclaim talents you don’t actually have. The trick is to come across as being truthful—because you are being truthful.

I’m therefore thrilled when former students write to thank me for helping them learn to think. I tell them that they helped me learn to think, about which compliment I’m utterly sincere. And I’m pleased that my students had the courage to take my courses despite my wellearned reputation as a tough grader. Courage is high on Aristotle’s list of virtues, between the vicious deficiency of cowardice and the excess of rashness/recklessness.

To my former students, I now offer this confession: Each of you is “The Precious Bundle,” too. You were right to insist on that ages ago, because each of you is uniquely precious and talented. Just don’t tell anyone I admitted this.

This is one in a series of four essays about humility, published in Bowdoin Magazine.

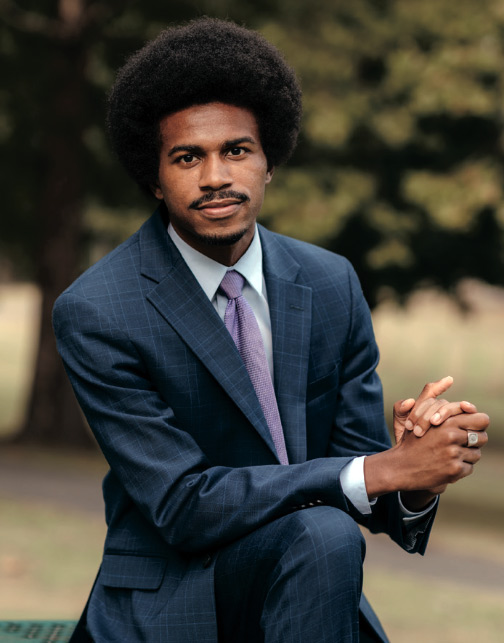

Barry N. Wish Professor of Psychology and Social Studies Emerita Barbara Held is a clinical and philosophical psychologist who has written several books, including Stop Smiling, Start Kvetching: A 5-Step Guide to Creative Complaining.

Francesco Ciccolella is an illustrator, graphic artist, and visual storyteller based in Vienna, Austria. His work has been featured in many publications, including The New York Times and The New Yorker. See more of his art at francescociccolella.com.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.