Respond Winter 2020

By Bowdoin MagazineUnited

In recounting the history of African American students at Bowdoin, the magazine’s reporting skipped from John Brown Russwurm in the nineteenth century to the 1960s, but it missed historic efforts by Bowdoin students immediately after the Second World War. Returning veterans, unhappy to see campus discrimination, created a new, local fraternity, named Alpha Rho Upsilon, the Greek representation of “All Races United,” that African Americans and other minorities could join. In another case, when the Delta Upsilon chapter faced a veto from its national headquarters because it sought to admit its second African American member, it left the national and formed Delta Sigma, a Bowdoin local chapter. With nearly all social life at Bowdoin then organized by fraternities, these moves in the late 1940s were of major importance. The College could admit African American students knowing that they would not be pushed to the margins of campus life.

Gordon L. Weil ’58

Remembering Project 65

I enjoyed reading Ray Black’s article on the fifty years of the AF/AM society at Bowdoin. When I saw the artifact about Project 65, it reminded me why I got involved as a sophomore in 1963. I believed that at Bowdoin the common good was something we seek. So, the question for me was “what was I going to try to do about?” We traveled across the country recruiting in college vehicles that were built for Checker cabs. Then, we received support from the Rockefeller foundation. That support led to the critical mass of students that produced AF/AM society.

It is nice to know that the current Africana Studies Program fits well with President Joseph McKeen’s original charge to the College: “It ought always to be remembered, that literary institutions are founded and endowed for the common good, and not for the private advantage of those who resort to them for education. It is not that they may be enabled to pass through life in an easy or reputable manner, but that their mental powers may be cultivated and improved for the benefit of society.” I hope Bowdoin continues to get students to believe in the common good. Thank you and Ray Black for the article.

Ed Bell ’66

Photo IDs

The recent edition of Bowdoin Magazine is outstanding. The overall presentation and articles are clear and filled with important information. I have a suggestion in regard to the AF/AM/50 article. The article would have been much more effective and cogent if you had taken the time to include even some of the names of the persons in the pictures. I realize that this could not be possible for all. However, I think you could have made the attempt. To an old guy like myself, several were obvious. For instance, on page 36, there was a lovely photo of Wil Smith and his daughter, Olivia, on the gym bleachers. On page 40, there was a photo of late President Roger Howell with two students. On page 43, there was a great photo of once-in-a-lifetime athlete Matt Branche ’49 sitting with the long-time coach of track, Jack Magee. Matt starred in football, basketball, and indoor and outdoor track, and went on to become a physician. My brother, Dan Morrison ’48, told me of Matt’s great sports achievements as well as his outstanding personality. Consulting with some former students of several different age groups could have helped in this regard.

Bob Morrison ’52

Ed Note: The photos included in the article hang in the Russwurm African American Center and were curated there by staff in the Student Center for Multicultural Life, Diversity, and Inclusion. The photos there originate from various sources and, unfortunately, many do not include identification. While we can identify some people in the photos, other subjects are not known to current staff members. Because of this discrepancy, to be fair and consistent, we made the decision to reproduce the photos without captions.

A Lesson in Kindness

I recently returned from China, where I’ve been teaching, and was just able to sit down to my most recent copy of the Bowdoin Magazine. Reading Houston Kraft ’11’s [column] last night after dinner, I read some parts out loud to my family, and the story he recounted about Helga and her two hours alone in the airport brought tears to our eyes, and made us reflect on times in our own lives—times when strangers hadn’t stopped to be kind when we needed them to, how that affected us, and also how there have been times when we have or haven’t stepped up, and the reasons why. It led to a really deep discussion that evening. I remember Houston well, we were in the same year, and I'm so glad to see the work that he has continued to do after graduation. I appreciated how he broke down the reasons people don’t stop and the distinction between “nice” and “kind”—these are things that, as a society, we all need to think about and actively work on. I also worked in social services for about a year, and many of the clients we worked with confided that, when homeless or distraught, what hurts the most isn’t when people don’t give money, but just being ignored day after day, being treated as nothing. It breaks my heart. So, on behalf of everyone I’ve ever met (who have had similar experiences), when walking by people, at least make eye contact, smile, say hello. Even just a nod of the head. It costs you nothing, but it means something. Or, stop and talk—about the weather, sports, anything. In schools, at work, and in public places, a little intention and attention goes a long way.

Ouda Baxter ’11

Diphtheria Outbreak of 1886

One sentence in the Fall 2019 issue of Bowdoin Magazine caught my eye. It describes the conditions of tenement company housing at the Cabot Mill in Brunswick: “During the summer of 1886, the squalid conditions there produced a diphtheria outbreak that killed nineteen millworkers,” (page 64). The prior sentence reads, “the majority of the Franco-American millworkers, many of whom were children,” lived in those tenements. So, how many children died of diphtheria in the summer of 1886 in the neighborhood where mill housing was located? David Vermette, whose book, A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold Story of Franco-Americans, writes that, in examining Brunswick town records, he found “thirty-five children died between April and September of 1886…. These records also show that diphtheria, in that summer of 1886, was not an equal opportunity disease; without exception, the children who died that spring and summer had French names.” Vermette quotes the French Canadian pastor of St. John’s parish as saying the he had ministered at more burials than baptisms during that period.

According to Vermette, a Bowdoin graduate named Albert G. Tenney, Class of 1835, who was the editor of the Brunswick Telegraph in 1886, “mounted a campaign against the Cabot company and its neglected tenements,” along with Dr. Onesime Paré. Conditions improved, but not before Dr. Paré himself died of diphtheria not long after the epidemic of 1886.

Michael Guignard ’69

The Wedding Singer

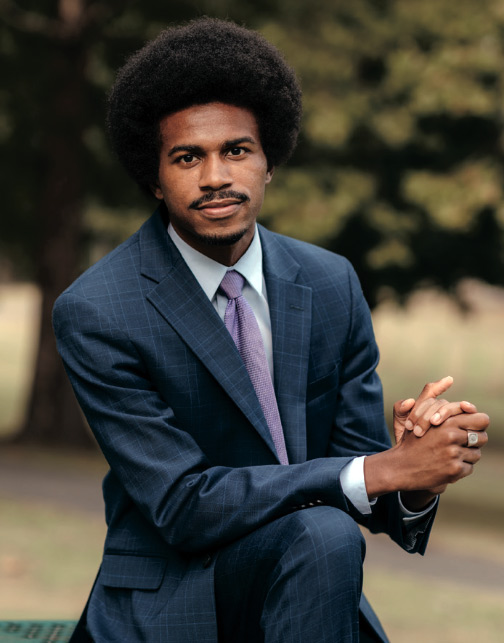

Congratulations to Bowdoin for presenting the Friedlander Award for the Common Good to Ryan Green (page 14). Bowdoin, indeed, also honors itself whenever it honors anyone who has overcome incredible adversity to achieve success in their life. The painful path that Ryan Green has followed to success and fame has been replete with impoverishment, fear, self-doubt, imprisonment, and many other frightening obstacles that most folks would never dare to challenge.

About a decade ago, my future wife, Dorothy Stachowicz, and I befriended a young lad who was studying voice at the University of Hartford in Connecticut. This student’s name was Ryan Green. He was known to us and to most everyone else as Speedo. Often, we would enjoy our Sunday morning breakfasts with Speedo. On the Sunday when we told him that we intended to marry he replied by suggesting that he sing at our wedding.

When our wedding day finally arrived, Speedo had graduated from the University of Hartford and had moved on to Florida State University to continue the development of his resplendent voice. True to his promise, he returned to Harford from Tallahassee, sang magnificently at our wedding ceremony, and then entertained our reception guests by singing selections from popular musicals.

Since that joyful summer day, Speedo has gone on to international acclaim as one of the truly great bass-baritones in the world of opera. He has performed often in major roles at the Metropolitan Opera, the Vienna Opera, and throughout the world.

August 8, 2008, was a spectacular day for Dorothy and me, a day which we will remember forever due in no small part to the thoughtfulness of a wonderfully talented and kind young man who has truly overcome.

Gerard O. Haviland ’61

Correction

I noticed an error in the article on the fiftieth AF/AM anniversary that was repeated in the first sentence on page 32 and again on page 34. The article states that John Brown Russwurm matriculated at Bowdoin in 1822. He entered Bowdoin as a member of the junior class in the fall of 1824. He had been teaching in Boston until 1824 (see the 2010 biography by Winston James, The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm: The Life and Writings of a Pan-Africanist Pioneer, 1799–1851; Russwurm’s name does not appear in the annual College catalogue until the October 1824 edition). The assumption of a four-year undergraduate Bowdoin career for Russwurm (and for others) is not always borne out by the facts, but—once in print—is difficult to correct.

John Cross ’76