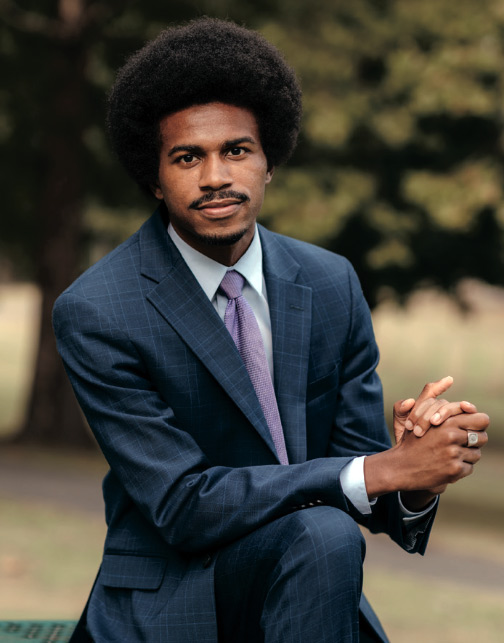

Exercising Kindness

By Bowdoin Magazine

"At a street festival in Venice, California, I happened to tell someone about my kindness work in schools who, months later, followed up with me and asked if she could nominate me for the Lay's Smiles campaign. Lay's then chose thirty-one people who are making an impact in local communities and made us the stars of their potato chips bags—all with the goal of inspiring even more smiles."

Photo: Courtesy of Pepsico

SOME OF MY FAVORITE MEMORIES of Bowdoin took place in Moulton Union, where, weekly, a small group of friends would gather to talk about kindness. We had formed an organization called OurKindness, and we would share stories of compassion, talk about why the world needed more empathy, and discuss practical ways to put these abstract ideals into real-life action. We sang songs of gratitude to the cardswipers, planned scavenger hunts that dotted the campus with generous surprises, and baked cookies to hand-deliver to the diligent studiers in the library during finals week.

The look of surprise elicited by these simple moments of care is what has always drawn me toward the practice of kindness; the heartwarming return on investment for altruism is, selfishly, way too good. But the idea that someone should feel surprised or even shocked by a small moment of human generosity has always nagged at me.

Why is it that doing things for the common good can feel so uncommon?

Shortly after my time at Bowdoin, I was on a plane next to a woman who was fidgety and enthused. I was tired and wanted to take a nap. In spite of signs that I was ready to go to sleep, she tapped me on the shoulder to introduce herself.

“Hi, my name is Helga!”

Nap time officially delayed.

As we talked, I described what we did in OurKindness at Bowdoin, and Helga got very serious and told me a story.

The last time she had flown was three years ago. She had scrambled to an airport because she had woken to a phone call from her dad’s doctor. He said, “Dad’s not doing very well” and told her to get to Arizona as quickly as possible.

Just as her plane was about to depart, the doctor called to tell her that her dad had passed away. For the three-hour plane ride, she sat in stunned silence, surrounded by strangers. When she got off the plane in Phoenix, she walked to the nearest wall, sat down, and wept.

And here is the part about Helga’s story that I’ll never forget: For two hours, she sat and cried, leaning against that airport wall, while nearly 3,000 people walked by.

Not a single person stopped.

I spend a lot of time in my work thinking about the importance of kindness in a world seemingly too busy for it. Kindness is one of those things that I think we collectively say is a good thing, but that we collectively just aren’t very good at.

Why? Why is it that we can universally agree on the value of a thing and so wholly be not very skilled at it?

To me, we need self-reflection (and the tools to do it well) to get to the answer. One of the most critical questions of our time, I believe, sounds like this: “What gets in the way of a more kind me?”

After my work at more than 600 schools around the world (and in my own uncomfortable self-assessment), I think it comes down to this: incompetence, insecurity, and inconvenience.

One of the most critical questions of our time, I believe, sounds like this: "What gets in the way of a more kind me?"

INCOMPETENCE

When we don’t know how to do a thing, we tend to avoid that thing. For me, the gym is a good example: There are so many machines I have zero understanding of in that place that I tend to relegate myself to a familiar three.

The same thing is true of kindness. Kindness is like an exercise that uses a thousand different muscle groups, but, as a culture, I think we really only practice two or three kindness “workouts” regularly. We’ve unintentionally reduced this area of huge possibility to a series of positive Post-it notes, free hugs, and the canonized sit next- to-the-new-kid-at-lunch.

In function, the fullest expressions of kindness (like the type Helga needed) actually require quite a few competencies in order to be executed well. Beneath the shiny idea of “being kind” lives a whole mess of hard-earned skills like empathy, emotional regulation, resilience, growth mindset, forgiveness, and active listening. That day in the airport, Helga surely didn’t need a Post-it note or a high five—she needed someone to sit with her in her suffering and share the weight of it with generosity and empathy and care.

In 2016, I cofounded CharacterStrong in order to help teach those missing hard-earned skills. We have worked with more than 1,600 schools to provide teachers and students the tools needed to effectively teach the social-emotional skills—the competencies of kindness—that actually allow for true culture change. We believe that the only pathway to a kinder world is to teach it.

INSECURITY

Legendary UCLA coach John Wooden said that character is what we do when no one is watching. But in a world that is more connected and interdependent than ever before, perhaps character is also what we do when everyone is watching!

We can’t show kindness in a vacuum. Every compassionate action we take exposes us to a variety of risks—like being judged or embarrassed or dismissed or laughed at or feeling like a failure. The most frustrating inverse relationship is this: The more you care, the more likely you are to get hurt. Our personal insecurities often interfere with our capacity for public good. When I am afraid of rejection or discomfort or humiliation, it can sometimes prevent me from acting on what I know is helpful, good, or kind.

INCONVENIENCE

As a world, I think we have “fluff-ified” kindness. Nearly every school I’ve been in has posters that say, “Throw kindness around like confetti!” But if being kind was as easy or convenient as tossing confetti, surely someone would have stopped to help Helga. Convenience, I believe, is the enemy of compassion.

A student once approached me after I spoke at a school assembly and told me that he thought he was a nice person, but not a kind person. I asked him the difference between the two, and the distinction has stuck with me: “Nice is reactive,” he said. “Kindness is proactive.”

Nice is easy. If someone is nice to me, I will probably be nice to them. If I agree with you, I’ll be nice to you. If you drop something, I might pick it up (especially if I know I might get something in return, like a thank you).

Nice is easy because it is “I”-oriented. Do I have time? Do I like you? Do I feel like it? Do I have anything to lose?

Kindness is different. Nice steps back while kindness steps up. Nice happens when there is time; kindness happens because we make time. Nice expects something in return, while kindness is free from expectation.

When we align ourselves with the deep purpose of kindness, it motivates action even when we don’t “feel like it.” We begin to do things that are hard and challenge us, which develops our capacity for compassion.

I think Helga deserves our persistent pursuit of this kind of self-improvement. For two hours, 3,000 strangers walked by her in her moment of deepest hurt. Sitting next to me on the plane, she explained it painfully well: “You know what I realized as they walked by? Kindness isn’t normal.”

Kindness isn’t normal.

That has been the foundation upon which I’ve built much of what I do. I want my life to be marked by the individual lives I’ve affected for good; my success should always aid in the successes of others. I want my work to cultivate conversations about compassion and to dismantle cultural narratives that, in any way, reduce connection, empathy, and generosity. I want to live in a world where kindness is the baseline.

It is a fight worth engaging in—to make kindness more normal in the world. To do the challenging work of self-reflection and ask, “What gets in the way of a more kind me?” To equip ourselves with the competencies necessary to do the complicated work of compassion. To release ourselves from the insecurities that so often unconsciously drive our actions (or inactions). To commit to being kind even when we’d rather settle for nice.

Because the only way we create a more common good is to do the uncomfortable—and uncommon—work necessary to live it.

This story first appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.