True Crime?

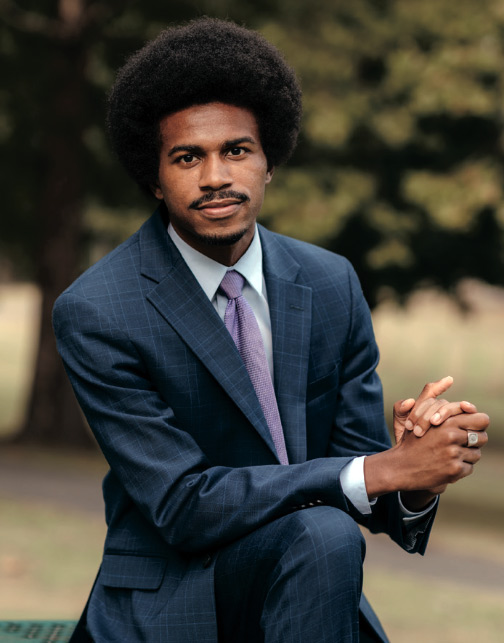

By Antoinette Kavanaugh ’90 for Bowdoin MagazineI am a forensic clinical psychologist who provides case evaluations and consultations in juvenile, criminal, civil, and capital court cases.

When I think of certainty in my work, I think first of wrongful convictions—more precisely, what we later find to be wrongful convictions.

To obtain a conviction, the state was able to prove to the judge or the jury beyond a reasonable level of doubt that this person committed this crime. It is as if they are telling the defendant, “I’m certain that you did this. I’m going to take away your civil liberty.” Years after the conviction, this certainty comes into question when DNA evidence, or some other type of evidence, proves this person did not commit the crime. When this occurs, it is considered a “wrongful conviction,” and the certainty of the judge or jury was wrong. According to the National Registry of Exoneration, this has happened more than 3,500 times since 1989.

The person who has been wrongfully convicted may bring a civil case. In essence, they are saying, “I’m suing the state for their mistake and for their certainty and for the years I spent in prison for something I did not do.” I have evaluated people who, because of a wrongful conviction, spent ten, twenty, or thirty years in prison.

When I conduct these evaluations, I explore the psychological damage that this wrongful conviction has caused the person and formulate an opinion about what kinds of things will impact their ability to reintegrate themselves into society. This is sort of a forensic certainty—built upon a combination of theories and research—that shows that, when this kind of thing happens, here are what we know are the consequences.

That certainty is shaky as well, because you have to look at the degree to which the person in question matches people in the sample from the research you’re basing your opinion on. To the degree they don’t, I need to question the certainty of that finding for that case. Sometimes there’s only a very limited body of research. And I can only use what’s available. For instance, when I look at actions that produce trauma or PTSD, those studies may not match the person in front of me. Studies that involve men may be solely about veterans. If the man I’m evaluating has been in prison since he was sixteen, and now he’s forty-six, he didn’t even have the opportunity to become a veteran.

Forensic psychologists look to data, research, and theories to increase the certainty with which we can render an opinion. We know that a body of knowledge will likely not completely overlap and perfectly match.

You have to be okay with a level of uncertainty, and you have to be able to verbalize for the court to what degree you’re uncertain and why.

You can still feel good about an opinion—“Given what we know, this is what I can tell you.” With some degree of certainty.

I’m also often called upon to help the court understand how a statement can be unreliable, what people think of as a false confession. We are led to believe that every confession is accurate. In psychological and legal terms, it’s not really a question of accuracy, it’s, “Is it reliable?” The factors that impact the reliability of the confession relate to the person confessing—youth and mental illness can make a person particularly vulnerable—and the circumstances of the interrogation, including the length and manner of questioning.

I was involved in a case where a college student believed he was getting messages from the news telling him he had murdered a woman in the community. She was well-liked, the murder occurred years ago, and the community marked the anniversary of her death. The police did not have a suspect. This young man went to the police and confessed to the crime. The police arrested and detained him. They were unable to locate any evidence against him other than his confession. It was as if they and the prosecutors were certain of his guilt. After spending more than a year in jail awaiting trial, his attorney asked me to evaluate him and the reliability of the confession. Once his attorney gave my report to the prosecutors, they dropped the charges against him.

Many people are certain that they or any rational person would never falsely confess. I think they believe the system is always just, in part because their knowledge of what happens during an interrogation is based on television or other pop culture. Based on my research and my own experience, I am certain the system is not always just, and I know that false confessions occur. Yet, each time I am hired to evaluate a defendant and a confession, in order to be objective, I have to start with the assumption that a confession is reliable. As I conduct my work, I look for indicators that make me less certain.

Next in this series on certainty: emergency room physicians Nick ’08 and Mike Larochelle ’08 »

Antoinette Kavanaugh ’90 is a licensed, board-certified forensic clinical psychologist. While working on this piece, she was absolutely certain that her new puppy was chewing a rawhide. It was her couch.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.