Medicine’s Ground State

By Nick ’08 and Mike Larochelle ’08 for Bowdoin MagazineAmerican surgeon, writer, and public health figure Dr. Atul Gawande wrote in Complications: A Surgeon’s Guide to an Imperfect Science:

“The core predicament of medicine—the thing that makes being a patient so wrenching, being a doctor so difficult, and being a part of society that pays the bills they run up so vexing—is uncertainty. With all that we know nowadays about people and diseases and how to diagnose and treat them, it can be hard to see this, hard to grasp how deeply uncertainty runs. As a doctor, you come to find, however, that the struggle in caring for people is more often with what you do not know than what you do. Medicine’s ground state is uncertainty. And wisdom—for both the patients and doctors—is defined by how one copes with it.”

Medicine is, at its foundation, a science. Medical students and residents embark on their journey by memorizing a vast knowledge base of how bodies and diseases should and shouldn’t work. But experience in clinical practice reveals a world far more complex: while science serves as a guide, medicine is more of an art. We both realized early in our careers that the “atypical is often typical,” and patients rarely follow what is described in the textbook. Nowhere is this more apparent than the emergency room. A patient presenting with a heart attack may exhibit a classic chest pain that began while shoveling snow, or they may simply report fatigue, nausea, or indigestion. Confusion may be the only clue to a serious underlying infection in an elderly patient. Translating medical education and science to the bedside requires humility, human connection, the desire to continually learn, and the ability to embrace and manage uncertainty.

Clinicians often juggle multiple forms of uncertainty simultaneously. At the crux of our field is clinical uncertainty. We gather information from a patient’s history and physical exam and incorporate scientific knowledge, evidence-based medicine, and patient values to guide our workup and treatment plan. Clinicians must account for diagnostic uncertainty (specificity and sensitivity of diagnostic testing), prognostic uncertainty (measuring disease progression and outcome risk), and therapeutic uncertainty (benefits and risks of treatment, choosing the correct individualized treatment). Risk scoring and stratification based in mathematical modeling guide the decisions we make at the bedside with each patient.

The best clinicians acknowledge that uncertainty is not a failure of medicine but an inherent aspect of providing clinical care. Thoughtful communication is essential to successfully managing the “uncertainty conversation” with patients. The physician-patient relationship today is centered on making a shared decision with patients about the care they receive. It is our job to provide patients with information, counsel them on risks and benefits of testing or treatments, and decide the right path to pursue. Should we perform a CT scan? Is a lumbar puncture warranted? How likely do we think the results will be positive? How will the results change the treatment plan? What are the risks and benefits of certain medications?

Learning to live with uncertainty in emergency medicine is not just a skill; it is imperative. Time is a significant constraint, and emergency physicians rely on continuously evolving evidence-based medicine, risk stratification tools, pattern recognition, and clinical gestalt. We must make rapid decisions with limited information; there is little role for rest-and-digest decision-making or second-guessing.

Uncertainty, rather than straining the relationship with our patients, often draws us closer. In a specialty rife with ambiguity, we find common ground with patients and their families who are coping with unfamiliar stress. In an ideal world, allaying our patients’ fears and concerns entails making a clear diagnosis and providing treatment and guidance; sometimes, the optimal outcome is simply ruling out life-threatening emergencies and alleviating symptoms.

In 2020, we entered a pandemic with exceptional uncertainty surrounding infection identification, disease progression, acute and long-term management, and health care systems’ methods of operational response. Most people knew someone who was sick enough to seek care at an emergency department, and many knew someone who experienced severe illness due to COVID-19.

Nick recalls the case of a fifty-five-year-old man who had a dangerously low oxygen saturation of 60 percent but was conversing comfortably. He asked the patient to have his family come to the hospital with concern that he was going to rapidly decompensate. The patient couldn’t believe this and, frankly, Nick couldn’t believe he was saying it either. This was early in the pandemic, and he couldn’t tell the patient if the current treatment pathways would be effective. The patient passed away within six hours despite “best practice” at that stage of the pandemic.

Uncertainty creates stress and anxiety for both patients and providers. Health care workers manage workload demands, cost containment, limited resources, and a more medically complex, aging population. Fatigue, noise, distraction, and the inherent pressure of the emergency department environment contribute as well. Burnout has been connected to poor communication and patient trust as well as poor patient outcomes. A provider’s ability to manage uncertainty in clinical practice can lessen long-term burnout and reduce emotional burden.

Precision medicine, artificial intelligence, improvements in diagnostic modalities, and other advancements in technology will have a significant impact on the practice of medicine in the future. Used properly, these tools may decrease uncertainty, personalize care, and create efficiencies. However, more information doesn’t always yield more certainty. The bedside relationship between the provider and the patient that accounts for human values and the ability to share in a decision-making process will always guide care.

Mastering the science of medicine conditions us as physicians to strive for clarity in diagnoses and treatments. Experience reveals that uncertainty not only prevails but also creates an environment for intellectual stimulation and medical advancement. It will always humanize and reinforce the provider-patient connection.

We must embrace and manage it alongside the individuals at the core of the practice of medicine: our patients.

Next in this series on certainty: professor of philosophy Scott Sehon »

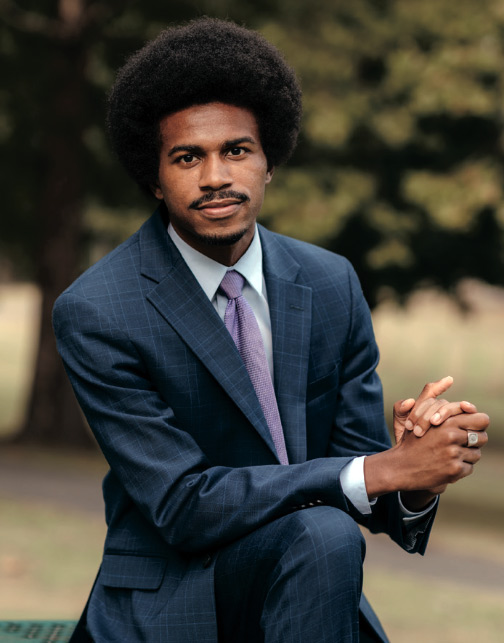

Nick Larochelle ’08 and Mike Larochelle ’08, two of six brothers to have graduated from Bowdoin, both graduated from the University of Vermont College of Medicine. Nick practices clinical emergency medicine in Concord, New Hampshire, and Mike in Park City, Utah.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.