A Boost from Uncertainty

By Professor Erika Nyhus for Bowdoin MagazineAs a professor in neuroscience, I often have students come to my office on their first day of first-year advising saying that they plan to major in neuroscience and go on to medical school.

Then they proceed to tell me all the classes they plan to take for their entire four years at Bowdoin. And if they do not get into chemistry their first semester, it will derail their entire plan.

Although I welcome their interest in my field and their ambition, I often have to remind them that Bowdoin is a liberal arts college and that the beauty of a liberal arts education is that they can take a class in something outside their comfort zone. Then I tell them the story of how, as a first-year college student, I tried to register for a history course to fulfill a college requirement, but when I was shut out I was forced to take Introduction to Psychology.

I had not even considered taking psychology because my high school did not have a psychology course, and I knew nothing about it. I found Introduction to Psychology so interesting that I ended up majoring in psychology, getting a PhD in psychology and neuroscience, and then teaching at Bowdoin. Sometimes I wonder where I would be today if I had gotten into that history course.

When I was asked to write this essay on certainty, my initial reaction was doubt about what I would have to say, since I am not an expert on certainty. But, just like my doubt about taking psychology, what I found was that a little uncertainty led me to explore something new and to learn a lot in the process. As luck would have it, I was at the annual conference for the Cognitive Neuroscience Society in Boston not long after the assignment, and one of the symposia was titled “Uncertainty Resolution Across Learning, Memory, and Decision-Making.” I thought I should probably go to the symposium to learn about uncertainty in order to write something somewhat coherent. As I sat in the audience, trying to absorb as much new information as I could, I learned about how important uncertainty is for learning and memory. This led me down a rabbit hole of reading papers on the influence of uncertainty on learning and memory.

Although this is still a relatively new area of research, uncertainty seems to be important for boosting learning and memory.

When we are uncertain, there is something unexpected in our environment, or there is a gap in our knowledge. This gap in our expectations versus reality is detected by two areas of the brain that are important for learning and memory, the hippocampus and the anterior cingulate cortex. The hippocampus is involved in memory for prior experiences and is active when prior experiences do not match the current experience. The anterior cingulate cortex is involved in detecting conflict and is active when there are information gaps in our knowledge.

Once activated, these regions signal the frontal cortex, a region of the brain that is highly developed in humans and is involved in cognitive control, guiding our thoughts and actions. The frontal cortex appraises whether the uncertainty can be resolved. If the uncertainty can be resolved, there is a release of dopamine and motivation to explore the environment to find information to reduce the uncertainty. The release of dopamine in the hippocampus leads to the enhancement of memory. But if the uncertainty cannot be resolved, the amygdala is activated, leading to anxiety and behavioral inhibition, which are detrimental to memory.

Understanding the neural mechanisms of uncertainty and memory brings up many more questions. Why do we have this drive to explore when faced with uncertainty? The neural mechanisms of uncertainty and memory may be related to our innate curiosity, or our motivation to seek information. Curiosity creates an evolutionary advantage, because it compels us to explore new environments and gain new information that may be useful in the future.

Is uncertainty always good for learning and memory? Some research has shown that there is an inverted U shape relationship between uncertainty and memory—some uncertainty is beneficial, whereas high levels of uncertainty are detrimental to learning and memory.

The inverted U shape relationship between uncertainty and memory reminds me of the inverted U shape relationship between stress and memory. The high levels of uncertainty and high levels of stress during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were likely terrible for our memory.

Do all people react the same way when faced with uncertainty? There is evidence that there are individual differences in people’s abilities to cope with uncertainty. If you are able to cope with uncertainty, then you will be more likely to explore and learn, whereas, if you are not able to cope with uncertainty, you will be more likely to have anxiety, behavioral inhibition, and a missed opportunity to learn.

I see these individual differences in tolerance of uncertainty in my own kids. My eight-year-old daughter has always enthusiastically faced new physical challenges, whereas my five-year-old son has always been more cautious. At five and a half years old, he has finally started to face uncertainty and explore more, which has led to learning many new physical skills. Recently he has started swimming without a floatie, pumping his legs so he can swing by himself, and riding a bicycle. These new skills have opened up a whole new world of independence and adventure.

I am certainly uncertain about certainty—as someone who is uncomfortable with uncertainty, I often have to remind myself to go out of my comfort zone to explore new things and learn something new, like I did when I took that introductory psychology course in college and when I agreed to write this essay. I hope to convey to my students that, when they encounter a new environment or are faced with a gap in their knowledge, by facing their uncertainty they can improve their learning and memory. You never know where that uncertainty will lead. They—or you! Or I!—may explore something new and interesting that could lead them down the path to a new area of study. And eventually, maybe, a career that they never before considered.

Next in this series on certainty: forensic psychologist Antoinette Kavanaugh ’90 »

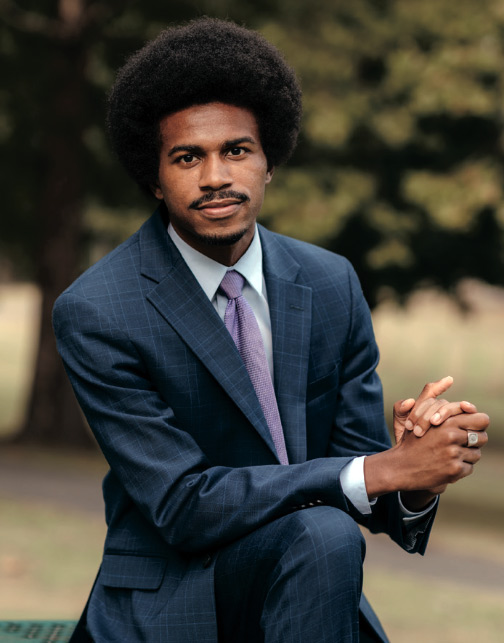

Erika Nyhus is an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Bowdoin. Her research focuses on human executive function and memory. Specifically, she is interested in how neural oscillations provide a mechanism for interaction among brain regions during memory retrieval and how we can change oscillatory activity to improve memory through noninvasive brain stimulation and mindfulness meditation.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.