Four Alumni Consider the Future of Obamacare

The student-run Bowdoin Public Health Club recently invited to campus four alumni who work in healthcare to have a discussion with students. They spoke about the Affordable Care Act and its uncertain future in light of President-elect Donald Trump’s promise to repeal Obamacare.

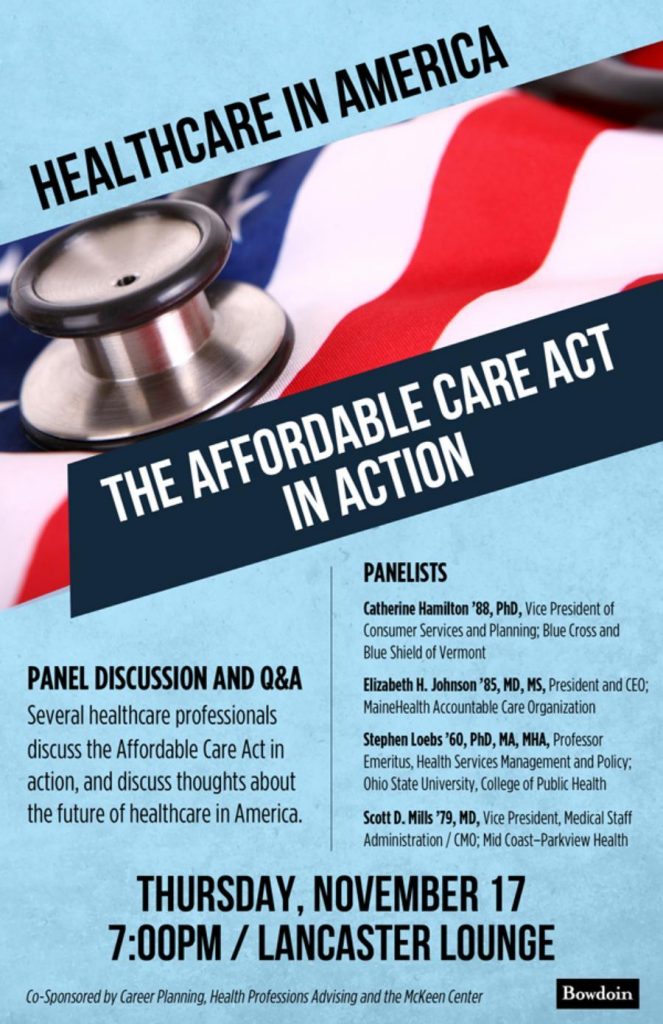

Meredith Sleeper ’17, who organized the event, introduced the four panelists: Catherine Hamilton ’88, vice president of consumer services and planning of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Vermont; Elizabeth H. Johnson ’85, president and CEO of MaineHealth Accountable Care Organization; Stephen F. Loebs ’60 professor emeritus of Ohio State University; and Scott D. Mills ’79, vice president and CMO of Mid Coast-Parkview Health.

Here are a few take-aways from the discussion.

What parts of the Affordable Care Act might stay, despite President-elect Trump’s talk of repealing the law?

Hamilton said that “guaranteed issue,” which prevents insurers from denying people coverage if they have a pre-existing medical condition, would likely not be repealed. She explained that advances in health science had changed the idea of what is a pre-existing condition, rendering old insurance practices unworkable. “We know so much about ourselves and our health now in utero. Without these consumer protections, think about a world where you would be uninsurable the day you are conceived,” she said.

The panelists also agreed that the new administration is unlikely to change the provision whereby parents can keep their children, up to age 26, on their healthcare policies.

In addition to expanding healthcare insurance to people who were previously uninsured, the Affordable Care Act is also designed to encourage innovations that reduce costs while improving health outcomes. “This side of the act will likely stay,” according to Johnson, “because we’re deep into trying different payment models and different ways to deliver care and we’ve got to keep doing it.”

What parts of the act will likely go?

The panelists thought the Affordable Care Act’s insurance mandate, which imposes a tax penalty on individuals who don’t buy health insurance, was the section of the law most at risk. “They can pull that tax penalty out,” Hamilton said. “That is pretty unpopular.” Also likely to go is the mandate for larger employers to offer coverage to their employees, she added.

In addition, Hamilton said that tax subsidies, which help about nine million people afford insurance policies when they buy them through the Act’s insurance marketplace, might be eliminated by the new administration and a Republican-controlled Congress.

“This keeps me up at night. The reason those nine million people have coverage through the online exchange is because they’re receiving help,” she explained. “The overwhelming reason Americans are uninsured in this country is because they can’t afford it, and those subsidies have helped with that.”

What parts of the Affordable Care Act have been successful?

Before Obamacare, approximately 47 million people in the United States did not have health insurance coverage. That number has dropped by roughly 20 million in a relatively short amount of time. “If you look at the history of healthcare reform in this country, with the exception of the passage of Medicare and Medicaid which happened 50 years ago, this has been the biggest change,” Hamilton said.

Much of that decrease was driven by the expansion of Medicaid, enabling more low-income people to become eligible for coverage. However, after the US Supreme Court ruled that states could opt out of the Medicaid expansion, only 32 states expanded Medicaid. Maine was one of the 19 states that did not.

What has not been successful?

In Maine, where Governor Paul LePage has vetoed efforts to expand Medicaid to cover low-income residents, there are still tens of thousands of people without health insurance. One of their few options for obtaining healthcare is from free clinics, such as Oasis Free Clinic in Brunswick. Loebs sits on the clinic’s board.

“There are a large number of people in this community, in this state, and in this nation, who have absolutely no health insurance, who have no purchasing power. They are basically out of any reasonable help in getting access,” he said.

He warned that any system proposed to replace Obamacare should focus on the “have-nots,” otherwise “we will continue to see healthcare disparities.”

Hamilton also pointed out there are not many choices for consumers who are selecting policies from the healthcare insurance market. For instance, in Vermont there are just two plans; in New Hampshire there is one. And the plans can be pricey for the middle class — who earn too much to receive tax credits — particularly if families are also juggling education costs.

Finally, the ACA’s attempted transformation of healthcare delivery and payment reforms is “incomplete,” Hamilton said. “It’s very early and these changes will take a long time…There is a lot of experimentation going on in Medicare; the results are mixed.”

How is the ACA trying to improve patient outcomes and lower costs?

The basic goal behind the ACA’s attempt to transform healthcare service and payments, Johnson explained, is to shift away from a system “designed around physicians and their needs and to rebuild it around the patient.”

The Act includes a proposal to set up accountable care organizations, which are made up of providers and hospitals that agree to tie payments to quality and cost of care.

Johnson runs one of these ACOs, the nonprofit MaineHealth Accountable Care Organization, which includes 1,500 physicians, 10 hospitals, and 378 practices, she said. Her organization sets up contracts, coordinates care, and analyzes data to better understand and use information to provide better care at a lower cost.

MaineHealth is trying to move away from paying providers for volume — i.e., number of patients seen and procedures performed — to rewarding value and outcomes. “So you don’t get paid on how much you do in a day, you get paid an upfront fee to take care of an individual or a population of patients,” Johnson explained.

Loebs said that at this point, ACOs are “the only hope we have for trying to rein in healthcare costs.”

Mills also explained that under the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid and Medicare have stopped paying hospitals when a discharged patient returns within 30 days, or when a patient contracts an avoidable infection during a hospital stay.

In addition, Mills said the ACA has pushed healthcare providers to integrate, work together, and set up shareable electronic records. “There aren’t too many people in solo practices anymore,” he noted. “You can’t practice medicine without an integrated care model because you need electronic records. We’ve seen an absolute change in the care model in the last eight years, with the ACA driving that.”

The Affordable Care Act has reoriented the healthcare system so that providers aren’t only treating patients with acute problems, but are also tackling preventive care, chronic care, and public health, according to Mills. “It’s moving us from a ‘sickcare’ system to a healthcare system,” he said. “I can’t tell you how much energy my healthcare system spends on thinking about preventive care and chronic care, and that wasn’t on the radar 10 years ago.”

Did the panelists propose other ideas for healthcare reform?

Right now, Medicare, the country’s largest insurer, covers 64 million Americans and spends $1.5 billion for medical payments every day, according to the panelists. Loebs said it is not so far in the future when healthcare will make up the largest component of spending in the US.

The biggest driver behind our high healthcare costs is the poor health of many Americans, which can be improved with healthier lifestyles. Additionally, medical expanses go up dramatically with our longer life spans and aggressive end of life care. “One of the largest components of expenditures in the US are expenditures for people in the last year or two of their life,” Loebs said. “As a nation, we have to come to grips with that.”

Hamilton said an ideal future healthcare system would be founded on a universal healthcare system much like Switzerland’s. She also would like to see a population of “community health workers,” trained to work with the elderly, people who have chronic illness, and employers.

In addition, with many millions of Americans buying drugs, Hamilton argued that the government should be collectively purchasing medicines. Loebs called it “an embarrassment that in the US we have a system where pharmaceutical companies can charge what they want and get away with it.”

“At the end of the day, we all have to keep changing,” Johnson noted. “Healthcare will look different in five years, ten years, twenty years. It continues to evolve and change.”

The event was sponsored by Career Planning, Health Professions Advising, and the McKeen Center