A Land Fit for (Some) Heroes: How the GI Bill Helped White Vets More Than Black Ones

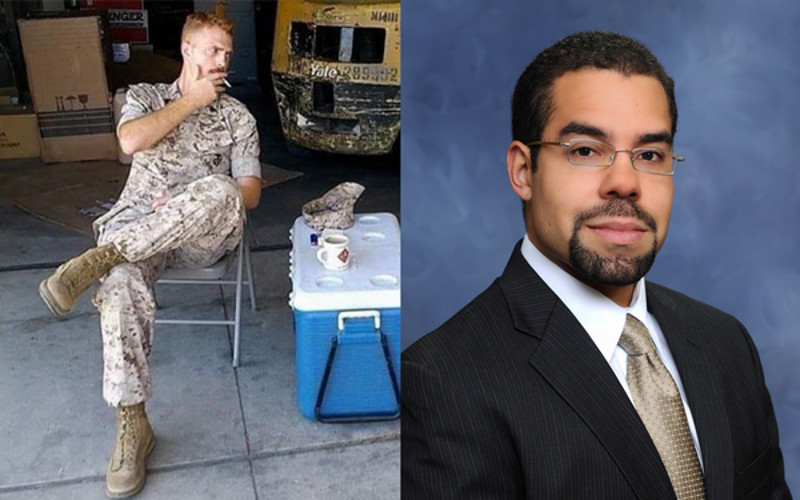

By Tom PorterFor his summer research project, Daniel Hennelly ’26 has secured an Irma Cheatham Fellowship in Africana Studies to explore racial inequalities in how the GI Bill was implemented in the wake of World War II.

The Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1944, also known as the GI Bill, is one of the most seismic pieces of legislation passed in the US, giving returning war veterans access to benefits to help them achieve social and economic ability.

“The bill offered free school, guaranteed housing loans, and one year of unemployment benefits to more than ten million veterans,” said Hennelly, himself a veteran, having served eight years in the US Marine Corps. “Within five years of the bill being passed, some 50 percent of the US budget was being used to pay for GI benefits,” he added. “The GI Bill played a key role in the creation of the US middle class during the postwar years because it provided Americans with the two key things needed for economic and social mobility, education and home ownership. However,” he explained, “that middle class was largely white.”

Hennelly is pursuing his fellowship under the supervision of Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History Brian Purnell, a scholar of African American history with a particular concentration on the civil rights movement.

“An entire generation of recipients of GI Bill benefits had to negotiate these veterans' privileges within the nation's powerful social context of racial segregation and discrimination, a reality that produced disparate outcomes for millions of Black and white veterans during the World War II and Korean War era,” said Purnell. Although the GI Bill was supposed to treat all veterans equally, he added, Black veterans could not use the bill’s home loan or education benefits the same ways as their white counterparts.

During the 1940s and ’50s, many mortgage lenders and realtors denied loans to Black veteran homebuyers. “In fact,” Hennelly points out, “only 0.7 percent of the 1.3 million Black Americans who served in World War II were successful in getting home loans under the GI Bill.” Those who could secure the financing to buy a home, meanwhile, often found themselves excluded from new suburban housing developments that operated a “whites only” policy.

Similarly, in the education field, many Black veterans came up against racial barriers in seeking to enter colleges or universities, many of which operated a color bar (particularly in the South), or only admitted a very small number of Black people. “Despite this,” explained Hennelly, “Black veterans actually utilized the educational benefits of the bill more than white veterans, because many of them went to vocational, or trade, schools.” The number of trade schools in the US grew rapidly after the bill was introduced, from 800 in 1944 to around 4,500 by 1946. The problem, said Hennelly, is that these schools lacked federal oversight and were more interested in accessing government dollars than they were in providing any meaningful education or training. Consequently, many Black veterans gained little from attending these trade schools.

Indeed, stressed Hennelly, the question of lack of federal oversight is key to understanding why the GI Bill was so unfairly implemented. In order to get the bill passed, concessions had to be made, particularly to racist southern Democrats who feared the legislation could undermine segregationist policies. “The implementation was decentralized, giving individual states the responsibility for overseeing the disbursement of educational and housing benefits.”

The original GI Bill expired in 1956 but has been replaced by similar legislation, known by the same name, guaranteeing certain assistance for US military veterans. Furthermore, federal civil rights legislation of the 1960s diminished the influence of individual states, helping lead the way to a more equitable distribution of benefits among Black and white veterans. “Today, for example, the majority of Black veterans—some 59 percent—own their own homes, compared to 42 percent of Black nonveterans,” said Hennelly.

Despite such advances, major racial disparities still remain, he observed, with significantly more white veterans owning their own homes than Black ones. Much of the damage was done during those crucial postwar years, said Hennelly, when the American middle class was being formed and when Black veterans, along with African Americans at large, were frozen out of the property market and prevented from accruing the sort of generational wealth enjoyed by many white families today.