On the Road: Experience BCMA Collections at Other Museums

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

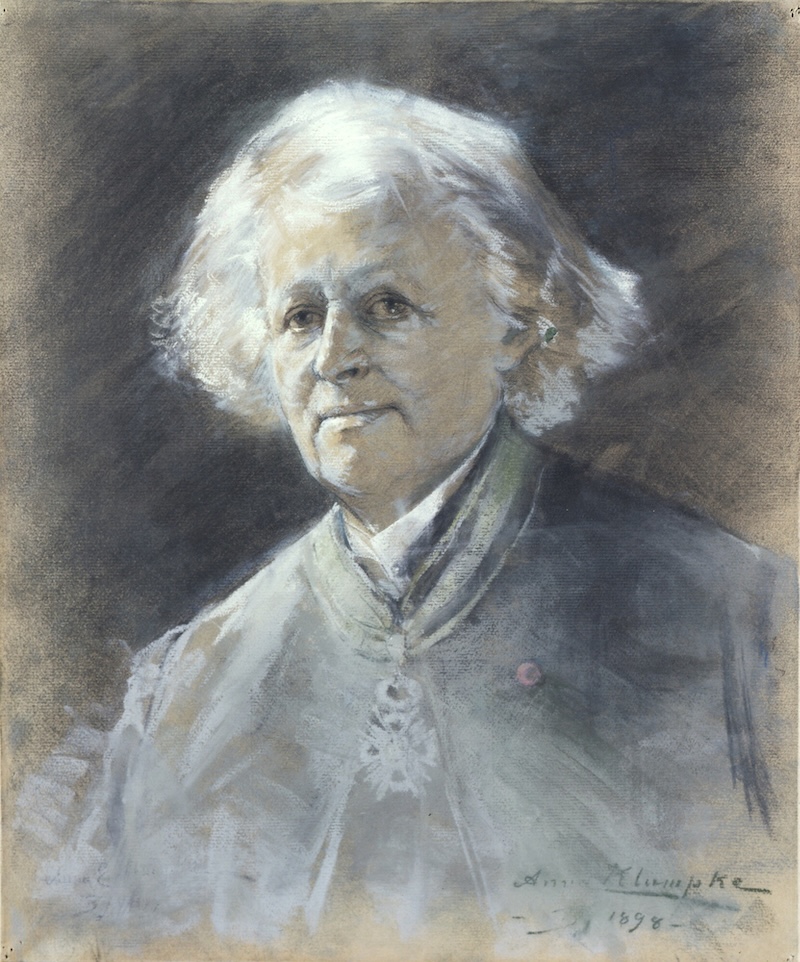

Portrait of Rosa Bonheur, 1898, pastel, by Anna Klumpke (American, 1856–1942). Gift of the Misses Harriet Sarah and Mary Sophia Walker, 1901.7.

With a collection of approximately 30,000 works of art, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art engages audiences by organizing exhibitions, hosting classes and research visits, and offering public programs. We also work with an extensive network of colleagues to lend works of art to other institutions, where they can be enjoyed in fresh contexts and by audiences far beyond Brunswick. Objects from the Museum’s collection were recently loaned to two groundbreaking exhibitions—one at Wrightwood 659 in Chicago, the other at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. BCMA Curator Casey Mesick Braun interviewed the organizers of these shows to learn how the Museum’s collections contributed to these important projects.

This past spring, the BCMA loaned Anna Klumpke’s 1898 pastel portrait of Rosa Bonheur to Wrightwood 659 in Chicago for their exhibition The First Homosexuals: The Birth of a New Identity, 1869–1939 (May 2–August 2, 2025). Organized by Jonathan D. Katz, Professor of Practice in Art History and Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and Johnny Willis, Associate Curator at Wrightwood 659, the exhibition explores the changing ways that society understood homosexuality after the term first entered the lexicon in 1869. Central to the exhibition’s argument is that, prior to this watershed moment, same-sex desire delineated a behavior rather than an identity. Willis elaborates, explaining that in 1869, the “Austro-Hungarian activist and journalist Karl Maria Kertbeny published the term ‘homosexual’ for the first time in recorded history, employing it in a pamphlet that argued against the criminalization of same-sex relations in Prussia. The term ‘homosexual’ was also accompanied by its opposite, ‘heterosexual,’ turning sexuality into something it had never been before—a binary between gay and straight. Yet, as language around sexuality became increasingly narrowed and restrictive, art picked up the slack, coming to represent an enormous range of identities, sexualities, and genders.”

Anna Klumpke’s pastel likeness of celebrated nineteenth-century painter Rosa Bonheur was placed in a section of the exhibition featuring portraits of people who came to embody homosexual identity, even if they did not openly or explicitly identify as such. For forty years, Bonheur was in a romantic relationship with a woman named Nathalie Micas. Willis explains that, when Micas passed away in 1889, “Bonheur built a relationship with the younger American painter Anna Klumpke. At the age of 39, Klumpke moved in with the 73-year-old Bonheur, producing several celebrated portraits of the renowned animal painter,” including the BCMA’s pastel. The exact nature of Bonheur and Klumpke’s relationship remains contested to this day. “The Rosa Bonheur Museum insists that Klumpke and Bonheur weren’t lovers, but rather close friends more akin to a mother-daughter relationship,” Willis notes. “Yet when Klumpke died in 1942, she was buried with Bonheur and her prior lover Nathalie Micas at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, under a tombstone that reads ‘Friendship is divine affection.’” Willis elaborates, stating how important it is to realize that, at this time, “lesbian relationships existed within a context of silence and fear, and that women often chose not to name their relationships and desires at a time when the available language was overwhelmingly pathological. This is to say, coming out of the closet wasn’t always liberatory.”

The First Homosexuals is intentional and deliberate in exploring the emergence of homosexual identity during a specific moment in time. In fact, one of the main goals of the project is to demonstrate that there is nothing inherently natural or stable about sexuality but is rather historically contingent. Willis argues that the “invention of the binary categories ‘homosexual’ and ‘heterosexual’ in 1869 created a polarizing discourse of sexuality that continues to shape the way we think and live to this day. By studying the ways in which art, language, and identity intersect and evolve, we hope that visitors come to see how profoundly sexuality is shaped by socio-historical context.” This continues to be apparent well into the twenty-first century, even without the benefit of historical hindsight to analyze patterns and attitudes. Willis emphasizes that they want visitors to understand that even while terminology is constantly evolving, “queer and trans people have always existed, and will continue to exist, even in the face of enormous adversity.” As the exhibition illustrates “the history of art represents the world’s richest archive of the history of sexuality, even if we haven’t regarded it as such.”

Shortly after The First Homosexuals debuted in Chicago, The Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened Superfine: Tailoring Black Style (May 10–October 26, 2025). This exhibition explores the many ways that Black people in the Atlantic diaspora have used fashion to define themselves and transform their identity from the eighteenth century to today. Included is the BCMA’s portrait of a gentleman, painted circa 1830. The identity of both the painter and sitter remain unknown. A staple in the long-term exhibition Re|Framing the Collection: New Considerations in European and American Art, 1475–1875, this oil painting pictures a Black man seated with his arm slung casually over the back of a chair, his gaze clear and assured. His coiffed hair and elegant suit suggest that he occupies an elevated position within society and the confidence that comes along with that station.

Exhibition curator William DeGregorio emphasizes that the BCMA’s portrait “perfectly incarnates the ease and self-possession that we are hoping to convey.” It is featured in a section entitled “Freedom,” which examines “how the growth of free Black communities in northern states precipitated a backlash that specifically targeted aspirations to fashionability. Poised, affluent, stylish Black men like the unfortunately unidentified man in Bowdoin's portrait were a threat to the white majority.” In representations of the time, Black men appeared as caricature, blackface, or minstrel performances. The creation and survival of portraits like this one, DeGregorio notes, “remind us that Black men found value and power in recording their likenesses, dressed in the latest fashions, and that ‘styling out’ has long been an important strategy for self-actualization.”

Both of these ambitious projects use art to explore topics that connect past attitudes to present concerns while also contributing to innovative scholarship—goals that are central to the mission of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and its responsibility to encourage thoughtful engagement with its collection to broad audiences. We are thrilled to contribute to these exciting curatorial projects.

Cassandra Mesick Braun

Curator, Bowdoin College Museum of Art