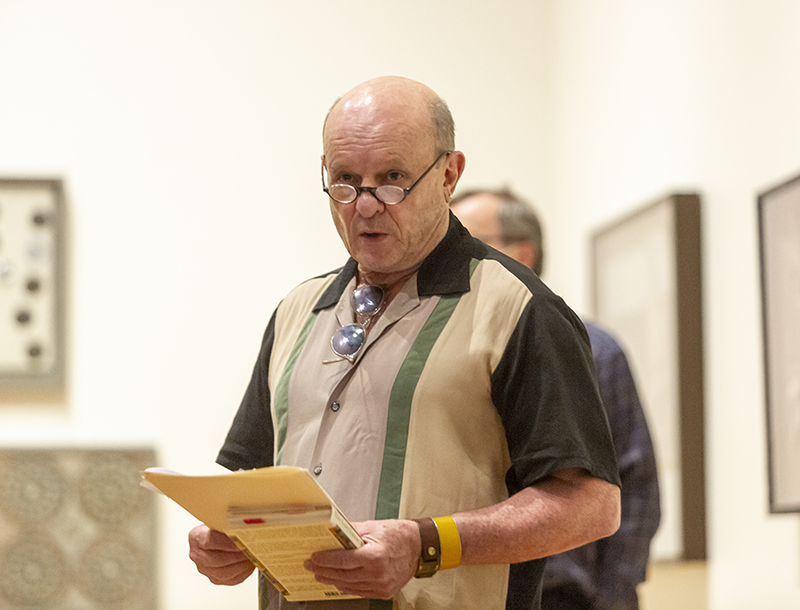

Roger Conover ’72 on "Mina Loy: Strangeness Is Inevitable"

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Roger Conover, Executive Editor emeritus, MIT Press, and Mina Loy’s editor and literary executor, is the editor of two important compilations of her verse: the Last Lunar Baedeker in 1982 and the Lost Lunar Baedeker in 1996. A member of Bowdoin’s class of 1972, and a former editor of Bowdoin’s The Quill, one of the country’s oldest undergraduate literary magazines, Conover has long been dedicated to recovering the lost works of avant-garde poets and artists. A generous supporter of the efforts of other scholars and creative practitioners, Conover generously shared his expertise and works by Loy that he has collected in the development of the Museum’s current exhibition, Mina Loy: Strangeness Is Inevitable, on view until September 17th.

In this interview, Conover describes for co-director Anne Collins Goodyear how he encountered Mina Loy and has carried forward his pathbreaking research on her over five decades.

- Could you say a little bit about how you first discovered Mina Loy?

I first encountered Mina Loy as a graduate student in English at the University of Minnesota in the mid-1970s. I was very interested in the "little magazines" of the early 20th century. It was in the pages of these radical, underground, alternative magazines that new poetic voices were being introduced, voices that signaled new tendencies in poetry that would contribute to the shaping of modernism and rise of the free verse movement. One of the poets whose work kept showing up in these magazines was Mina Loy. But who was she? Her work was astonishingly good, and unlike anything I had read before. Her work consistently appeared in magazines like The Dial and The Little Review, alongside the work of writers whose names were familiar, such as W.B. Yeats, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Marianne Moore, and Ezra Pound. Mina Loy's first poems appeared next to T.S. Eliot's first installment of The Wasteland and were once considered as consequential as his. But by the 1970s, she was not included in any of the syllabi or anthologies that mapped the development of modern poetry. Why? This was the beginning of what would become a lifelong quest. To recover the work of a missing modernist and bring her back into the conversation of which she had once been such a vital part.

- How did you become aware that this famous and highly regarded poet was also an accomplished artist?

My research on Mina Loy led me to meet many of the people who had once known her, many of whom were still alive in the 1970s, including Virgil Thompson, Kay Boyle, Malcolm Cowley, Djuna Barnes, Peggy Guggenheim, Charles Henri Ford, and Julian Levy. I was in my 20s. They were in their 70s, 80s, 90s. And they had a great interest in sharing their memories of Mina Loy, whose talents had made a profound impression on all of them. Several of them had owned paintings by her, and attended the exhibitions of her art work curated by Julien Levy (in 1933) and Marcel Duchamp (in 1959) in New York. It was impossible for them to recall Mina Loy the poet without also recalling Mina Loy the artist. But whereas the poems could be found in the pages of little magazines, the art work was more difficult to trace. It has taken literally 50 years of devoted sleuthing to assemble the works now included in the Bowdoin exhibition, Mina Loy: Strangeness is Inevitable. I should note that I am grateful that several other private and institutional lenders were generous enough to share their works by Loy, and I thank curator Jennifer Gross for her work, in association with the BCMA, in assembling them here.

My research on Mina Loy led me to meet many of the people who had once known her, many of whom were still alive in the 1970s, including Virgil Thompson, Kay Boyle, Malcolm Cowley, Djuna Barnes, Peggy Guggenheim, Charles Henri Ford, and Julian Levy. I was in my 20s. They were in their 70s, 80s, 90s. And they had a great interest in sharing their memories of Mina Loy, whose talents had made a profound impression on all of them. Several of them had owned paintings by her, and attended the exhibitions of her art work curated by Julien Levy (in 1933) and Marcel Duchamp (in 1959) in New York. It was impossible for them to recall Mina Loy the poet without also recalling Mina Loy the artist. But whereas the poems could be found in the pages of little magazines, the art work was more difficult to trace. It has taken literally 50 years of devoted sleuthing to assemble the works now included in the Bowdoin exhibition, Mina Loy: Strangeness is Inevitable. I should note that I am grateful that several other private and institutional lenders were generous enough to share their works by Loy, and I thank curator Jennifer Gross for her work, in association with the BCMA, in assembling them here.

- Could you tell us about how you were able to acquire examples of her art?

Mina Loy lived a peripatetic existence. She was born in London, attended art school in Paris, lived in Florence during World War I, moved to New York, traveled in Mexico, then headed back to Paris before returning to New York, and spent her final years in Colorado. In the pre-internet, analog era, the only way to know what traces Mina Loy might have left behind was to go to the places she lived, ask questions, find people who had once known her, and hope for good luck. I knocked on many doors that did not open, wrote to many people who did not answer. But once in a while, persistence was rewarded. To give but one example, I knew that her first husband, Stephen Haweis, had spent many years living on the island of Dominica, in the West Indies, after his divorce from Mina Loy. From reading Mabel Dodge Luhan's memoirs, I knew he was a painter. And from reading his obituary, I knew he had a niece who was still alive. So I went to see her in a remote village in British Columbia, and she gave me the name of a few people in Dominica who had been friends of her uncle. If I had not gone to Dominica to follow up on her leads, the self-portrait of Mina Loy (Devant le Miroir, ca. 1905) that occupies the first wall of the exhibition would never have surfaced. Each piece in the exhibition has a story. These works were for the most part not acquired through auctions and galleries, but through research and the cultivation of relationships over time.

- What have you found most interesting about the current exhibition?

I have known, and lived with, a number of the works in this exhibition for decades. But seeing them recontextualized within the galleries of Bowdoin College I see the strangeness of Loy’s art anew. And listening to the observations of poets and artists who have never seen this work before, I have learned how to see the work again, as if for the first time, as if I have never seen it before, as if I have not lived with it and did not know it until now. I am extremely grateful for the experience of re-seeing thanks to the first-seeing of others.

- Is there anything you have found surprising?

There are many aspects of the Mina Loy exhibition experience that I find surprising. If I had to choose just one, I would say I was not prepared for the impact that this show would have far beyond Brunswick, Maine. The number of curators, scholars, and researchers who have come to Bowdoin from Europe for the sole purpose of seeing this exhibition has been impressive, to say the least. I was once concerned that the show might not get the attention it deserves, because it is not in New York. But its out-of-the-wayness has proved to be a draw, and an attraction. Who would have imagined that Il Manifesto, the daily newspaper of the Italian communist party, would send a critic to report on the exhibition and devote a page to covering it: https://ilmanifesto.it/mina-loy-coscienza-femminile-in-stranezze-lunari. Other coverage of the exhibition is available through the exhibition website.

- In your talk about Loy in April you spoke about the interest several contemporary musicians have taken in her work. – Could you say more about that connection? – What makes Loy’s work so compelling today?

Yes, I spoke of Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth), Billy Corgan (Smashing Pumpkins) and several other contemporary musicians--including the hip hop artist Busterwolf who produced an entire album as an homage to Mina Loy. Busterwolf will be performing at Bowdoin College on September 14, and we will have a public conversation that will address your question. In the meantime, I refer your readers to the talk you reference: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BbW1Ac_1FZI

- Do you envision undertaking future projects on Loy’s work?

Yes. I don't think I will ever stop working on Mina Loy. Right now, I am working on a new edition of her writings. But the project that most excites me is a screenplay about the phenomenal love story between the poet-artist Mina Loy and the poet-boxer Arthur Cravan, which I have long believed is a story destined to become a film.

- Anything else you’d like to share?

Thank you for the opportunity to share these thoughts. The only thing I would like to add is that it's worth choosing one's subjects carefully, and staying with one's convictions. I am enormously grateful to you and to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art for making this exhibition and the related catalogue, published by Princeton University Press, possible.

Illustration:Unidentified photographer, Mina Loy Dressed for the Blindman’s Ball. 1917, gelatin silver print. Private collection. Photography by Luc Demers.