Groundhogs, Iceworms, and a New View of the North

By Michael QuigleyAfter months spent working my way through Donald MacMillan’s vast photographic collections I was happy to take a break. I had been reformatting images and updating data to make nearly 8,000 of his images publicly accessible through the Arctic Museum’s online database for the first time.

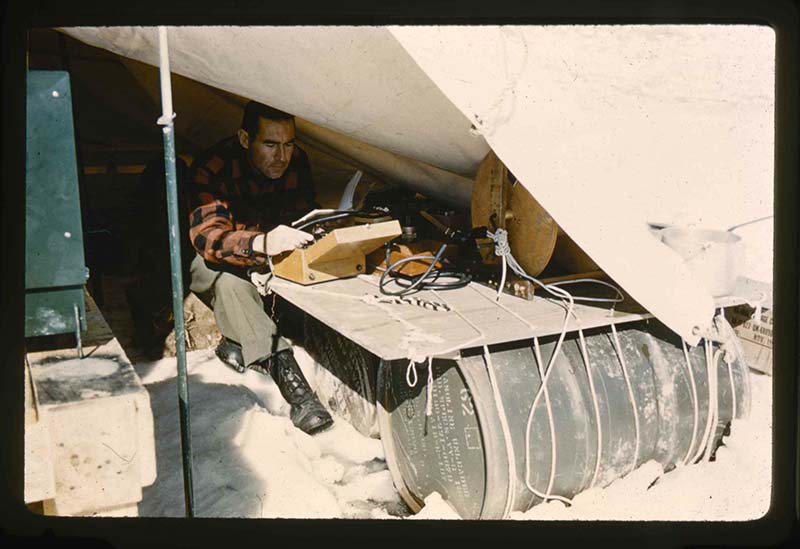

Stanley Needleman, Unloading of C-130 Aircraft of Equipment, Supplies and Vehicles in the Snow, Centrum Lake, northeast Greenland, May 5, 1960. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

Here was a collection that picked up chronologically just about where MacMillan’s photos left off, yet what a different northern world these images depicted. Gone were the intimate portraits of locals, small gatherings, cultural exchanges, and ever-present cramped quarters of the schooner Bowdoin Mac captured so well. Here were large-scale, heavily funded operations incorporating massive aircraft, sophisticated scientific equipment, and all sorts of sci-fi-esque heavy machinery out on the barren ice. What was the point of all of this? What were these people doing out there with all this high-end gear? Who was paying for it, and what were they hoping to achieve? Most perplexingly, how did the North, as depicted in one museum’s photographic collection, change so drastically within the span of a few short years?

Stanley Needleman, Balloon Filled with Helium to Measure Ozone Layer by Telemetering Data to Record, June 1958. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

The photographer was Stanley Needleman, a geophysicist working as project leader for Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories during Operation Groundhog. The objective of this US military operation was to identify suitable runway sites in remote parts of northern Greenland while collecting detailed data on weather patterns, water and drainage conditions, soil types, available construction materials, flora, and fauna. The investigations were part of a larger effort on behalf of the US military to understand the Arctic environment and to possibly establish a base in northeast Greenland.

The US military began operating in Greenland when the Kingdom of Denmark fell to the Nazis in 1940. An agreement was made at the time allowing the US military access to Greenland for the protection of the Danish colony and the North American continent. During the war, the island proved a strategically important midway point for planes to refuel en route to and from Europe. As World War II gave way to the Cold War, Greenland’s geographic advantage to the United States shifted from its proximity to Europe to its proximity to the USSR. Rather than relinquish its foothold in the territory after the war as originally agreed, the US military doubled down on the island in preparation for war with an adversary just over the North Pole.

Stanley Needleman, Dan Krinsley Reading Thermistor Cable Meter and Measurements, Centrum Lake, northeast Greenland, May 31, 1960. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

By the late 1950s the United States was deeply entrenched in northern Greenland. It had quietly relocated an Indigenous community to build Thule, the superpower’s second largest military base, completed with the labor of some 10,000 soldiers, in an effort that has been compared to the construction of the Panama Canal. Construction crews had also carved out Camp Century, a nuclear-powered city of 200 inhabitants, beneath the ice cap, and the United States was in the midst of carrying out Project Iceworm, a futuristic scheme involving hundreds of nuclear missiles, aimed at the Soviet Union, in constant motion on a 50,000 square mile network of rail lines traversing tunnels below the ice.

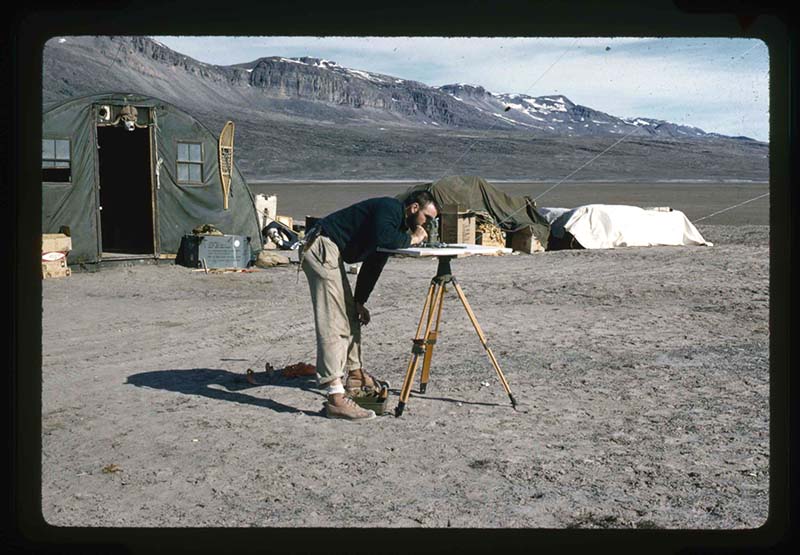

Stanley Needleman, Kinsellar, Surveyor, is Checking Base Line of Airstrip from Centrum Lake Base, Centrum Lake, northeast Greenland, July 1960. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

These incredible feats of engineering, along with the successful use of sophisticated new weapon technologies and the potential for human combat in the far north, depended upon extensive scientific knowledge of a heretofore unfamiliar and little-studied environment. The US military achieved its goals by funding a massive new ecosystem of defense contractors and university research programs focused on environmental sciences, geosciences in particular, and offering logistical support for fieldwork in Greenland. During the early Cold War, the territory became a laboratory for a suddenly booming academic field.

Unidentified photographer, Army Helicopter H-34 Picks up Needleman from Centrum Lake. Ice Still on Lake, Centrum Lake, northeast Greenland, June 1960. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

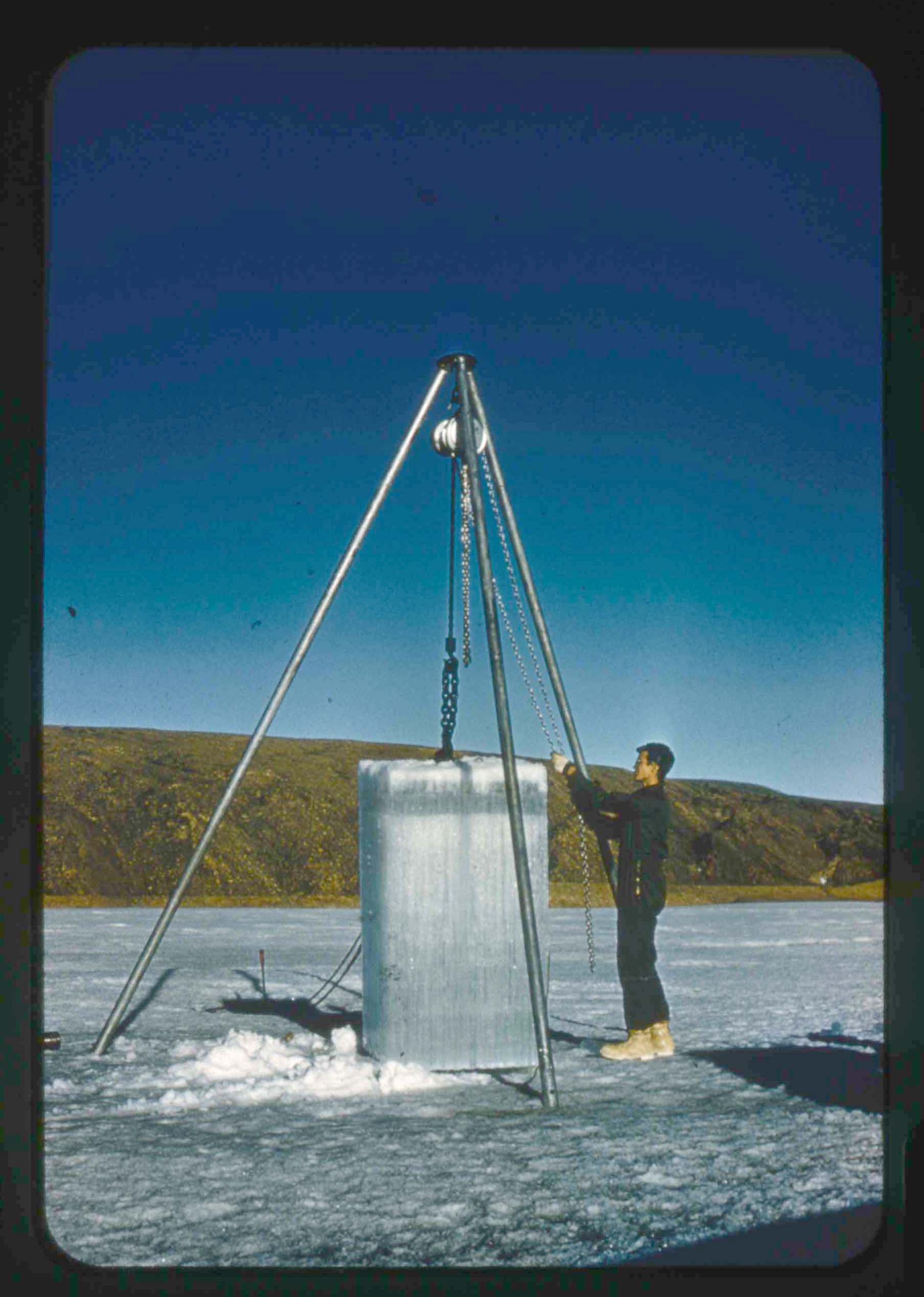

Stanley Needleman, Cabaniss Removing Block of Ice Cut from Lake for Strength Tests, Lake Peters, northwest Greenland, August 1, 1956. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

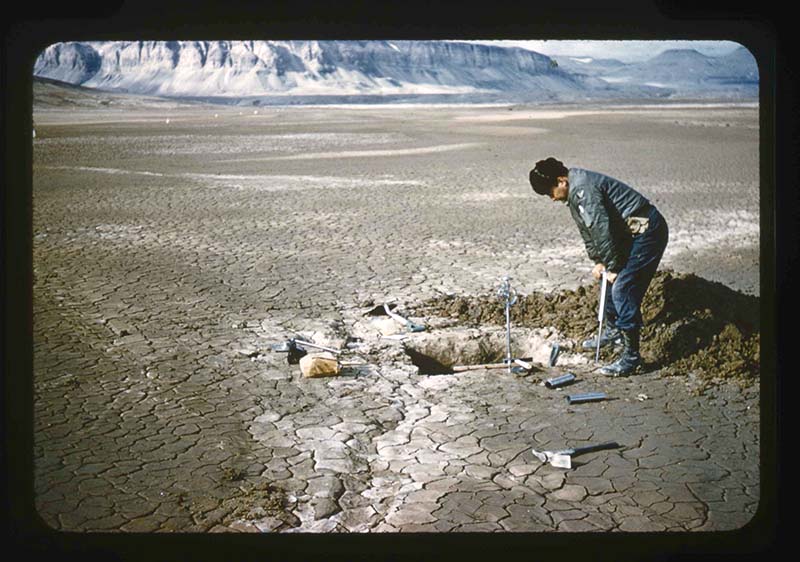

Unidentified photographer, Testing of Bearing Strength on Runway Site at Bronlunds Fjord. Stan Needleman, Bronlunds Fjord, northeast Greenland, August 1957. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

Stanley Needleman, Drilling 90 Drill Holes through the Snow and Ice Cover of Centrum Lake, Centrum Lake, northeast Greenland, June 30, 1960. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

Stanley Needleman, Tracked Weasel Transporting Personnel and Equipment through Water and Moat, Centrum Lake, northeast Greenland, June 1960. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.

Taken together, these holdings represent a unique and expanding resource for students of the Cold War, the history of polar science, or the role of academics in the United States military industrial complex. As for myself, after a happy sidetrack, I’ll be diving back into the Arctic Museum’s seemingly endless cache of soon to be rediscovered and newly accessible photographic gems.

Stanley Needleman, C-54 Aircraft Flies Overhead as a Rescue Aircraft While C-130 Aircraft Lands, Centrum Lake, northeast Greenland, May 5, 1960. 35mm slide. Gift of Stanley Needleman.