Hoping for the Best, Training for the Worst

By Mike Quigley, Assistant Curator

Caring for some 41,000 objects for posterity takes a lot of work. The diverse collection of the Arctic Museum includes irreplaceable items made of paper, film, stone, metal, wood, bone, skin, fur, feather, and a myriad of other organic and man-made materials. Some of the most common ways these materials can deteriorate over time include physical handling, exposure to light, munching of insects, and storage in incorrect or fluctuating temperature and humidity. It’s a museum’s duty, through the practice of collections management, to mitigate these long-term threats to the greatest extent possible.

Yet even the most stringent collections management regimen can be undermined, entire museum collections lost in the blink of an eye, by a single catastrophic event like a hurricane or fire. In just the last few years, museum collections have suffered significant losses as a result of hurricanes in New York, Texas, and Puerto Rico, and from 2018’s wildfires in California. And of course, disaster can strike regardless of the weather, as the particularly devastating, nearly complete loss of the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro to an electrical fire last September reminds us.

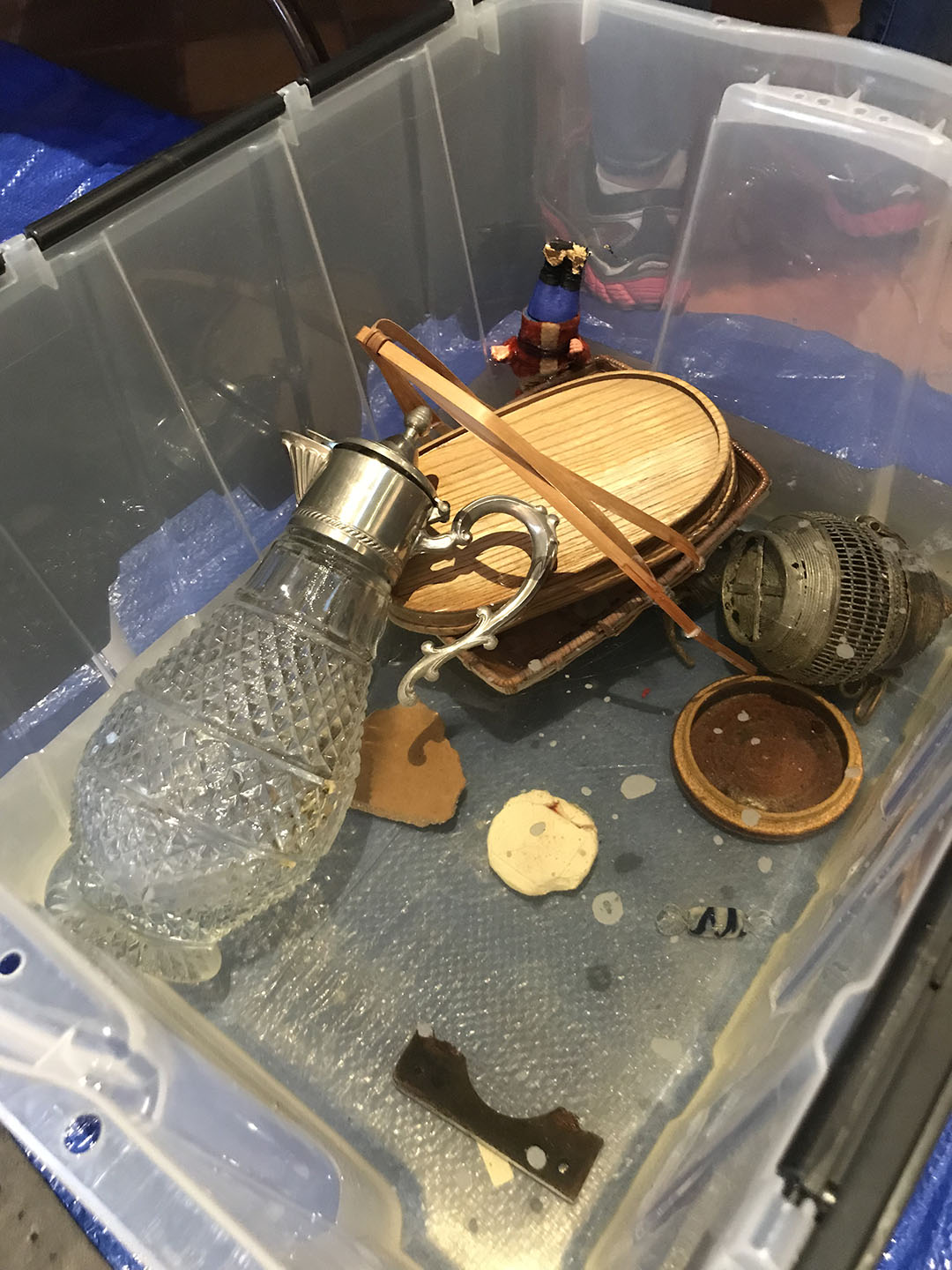

“Priceless artifacts” in need of salvage during a training exercise. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

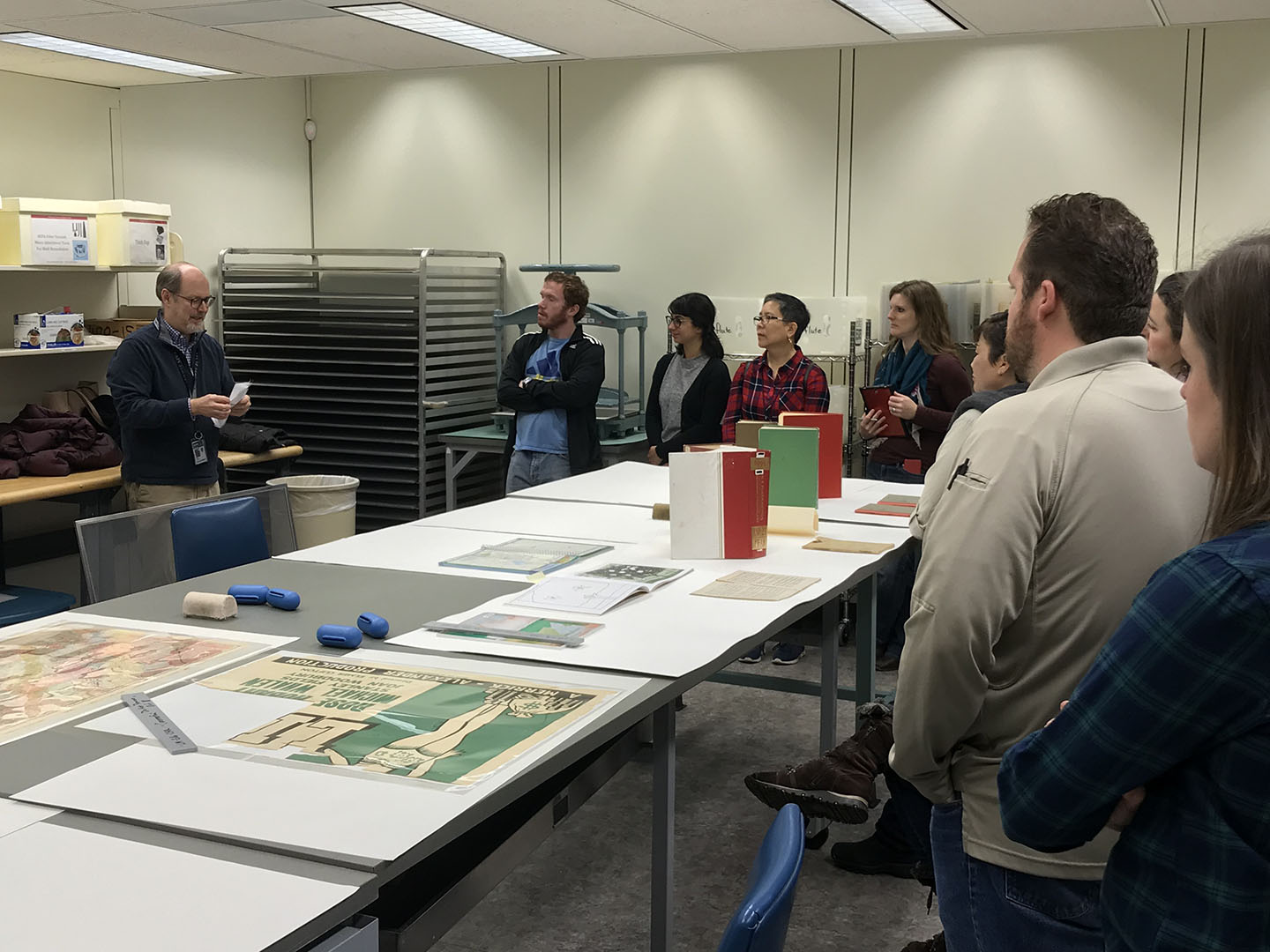

It was with all of this in mind that I applied to the Heritage Emergency and Response Training (HEART) program held at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, December 10 – 14, 2018. The training was organized by the Heritage Emergency National Task Force, a public-private partnership co-chaired by the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative and FEMA’s Office of Environmental Planning and Historic Preservation. I was honored to have been selected, through a competitive nation-wide application process, along with 24 other participants coming from a wide variety of museum specialties and library, archives, and emergency management fields, representing 16 states and the Territory of Puerto Rico.

The training prepared us to address emergencies and disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, and fires. We benefited from realistic, hands-on training in risk and damage assessment, disaster planning, health and safety, emergency evacuation and salvage of museum objects, crisis communication, and team building.

One of the most memorable sessions was an afternoon exercise in which the group was faced with a mock disaster scenario requiring all 25 participants to work together to safely evacuate a museum collection from a flood zone. Donning our hardhats and yellow safety vests, we assigned team roles; interacted with both friendly and contentious stakeholders (roles played by scenario organizers); and set to work documenting, packing, and moving priceless artifacts (cheap thrift store purchases) out of the museum (an unused Smithsonian building on the National Mall) to safety. The evacuation was arguably successful, but more importantly, the exercise itself was a great learning experience, demonstrating the difficulty and importance of maintaining communication and functioning as a team during a particularly complex and chaotic event.

Back at Bowdoin I plan to draw on what I learned in Washington, DC, as I collaborate with museum and college staff to update the Arctic Museum’s emergency plan. Working our way through this critical, if admittedly dull, document will accomplish several things. First, it will force us to reconsider our threats and to ensure that we’ve done all we can to prevent disasters from affecting the collections in the first place. Second, it will re-establish what individual museum staff members’ roles might be during particular emergencies. Third, it will ensure that we will either have on hand or know how to quickly acquire the materials, space, and help we may need for collections salvage. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it will require us to reach out across campus and beyond to coordinate our plan with municipal first responders, institutional safety and security professionals, private vendors, and the greater museum community. Understanding the diverse perspectives and skills they bring to the table and forging positive working relationships with them before disaster strikes will be critical to a response and recovery effort when it does.

In the meantime, we’ll continue our daily battles against the ravages of overhandling, light, insects, and fluctuating environments, preserving our unique collection of cultural heritage as best we can for future generations.