The Cat's Out of the Bag

By Dallas Denery for Bowdoin MagazineProfessor of History Dallas Denery reveals a story from his life before academia, in which he begins as a punk rocker and ends as the author of a piece in a magazine for cat lovers.

Shortly after the September 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake in California, I found myself in need of a job. My four-year punk rock “career” had finally petered out in July. Our label had dropped us after our first album failed to find much of an audience beyond our local fanbase, and a three-month cross-country tour, though tremendously educational (among other things, I now knew where to find the world’s secondlargest twine ball), had done little to make it seem like stardom was just over the horizon. A bit disappointing to be sure, but not devastating, as a career in music wasn’t a particular ambition of mine.

That aside, punk rock had never paid the bills, so all along I had been making ends meet summarizing legal depositions in my little apartment in San Francisco for a Berkeley law firm. Unfortunately, the earthquake had made it impossible to cross the Bay to Berkeley—the Bay Bridge was partially destroyed, and BART had been shut down for inspections. My days as a deposition summarizer, like my days in punk rock, were through.

Finances dwindling, I decided to look for whatever full-time work I could find, and so, one day, I walked from my flat in North Beach to a Financial District job placement agency. I met with a woman in her mid-forties (her name forgotten after all these years) dressed in black, with hair dyed to match her clothes. She asked about my work history, how fast I typed, when I could begin, and then she looked at my résumé.

“I see here you studied philosophy in college. I study philosophy too, mostly in connection with my ongoing investigations into ancient Egyptian theosophy.” She then stood up, went to the window, and asked me to stand next to her. Both of us now looking down from twelve floors up at the busy afternoon streets, she asked, “Do you see all those people down there?” I told her that, yes, I could see them. “I sometimes think they are nothing more than ants that I could squash with my thumb.”

It was not the sort of thing I ever thought I would hear at a low-level corporate job interview, and its connections to theosophy—at least given my limited knowledge of theosophy—remained murky. I don’t remember how I responded, if I responded at all, but it did leave me with a somewhat warped expectation of the mysteries awaiting me just below the surface of the San Francisco legal world.

Within a week I was working full time as a legal secretary. I had never worked in an office, much less as a legal secretary, and while I wouldn’t call it fun, it was interesting. I suddenly found myself submerged for eight hours a day in a world entirely new to me, with its own traditions and passions. One of those passions, it turned out, was for cats. All of my coworkers were cat crazy. They covered their desks with framed cat photos and daily tear-away cat calendars. They hung motivational posters from the walls showing kittens suspended from twine (“Hang in there, baby!”). As I didn’t much care for cats and was the only man in the steno pool (as we already no longer called it in 1990), all of this left me outside much of the daily secretarial socializing and conversation that happened before and during and sometimes after work. Sadly, none of this absolved me from having to join in one of the office’s core traditions, the Secret Santa.

Every Christmas, every legal secretary needed to purchase one present to be randomly distributed among us at the annual office holiday lunch. I am a terrible gift shopper and innately a bit of a cheapskate, but I did like my coworkers who, to a person, were easy to work with and made efforts to make me feel part of the team. My artistic impulses muted, what with my band no more and my days taken up transcribing endless tapes of letters and legal briefs, I decided that my Secret Santa gift would be a cat-themed Christmas story given to my fellow secretaries.

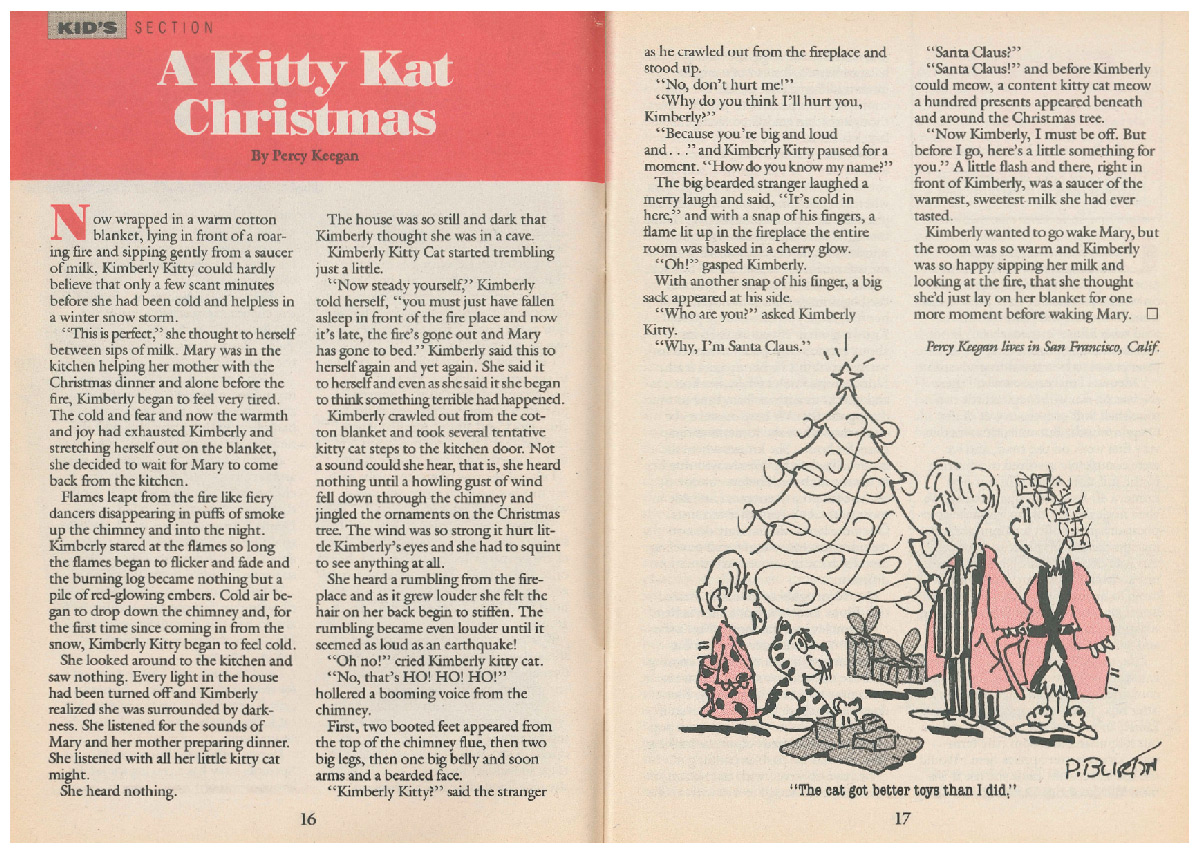

I could attempt to enter their cat-loving social world while not spending a cent and not actually having to participate in their cat-loving social world at all! The result was “A Kitty Kat Christmas,” the story of how Kimberly Kitty Cat discovers the true meaning of Christmas in three chapters totaling eight pages.

Briefly: Kimberly is caught in a snowstorm, cold, shivering, maybe lost, and certainly scared, until Mary, her five-year-old owner, finds her, brings her inside and sets her in a blanket before a roaring fire (Chapter One).

Having been so cold and scared and now being so warm and comfortable (though possibly coming down with a cold—“meow-choo!”), Kimberly dozes off, only to be suddenly awakened by a large man in a red suit who leaves a mountain of gifts beneath the Christmas tree (Chapter Two—the dream sequence).

In the morning, Kimberly awakens, surprised to discover not a mountain of gifts beneath the tree, but only a few, because Mary’s family is not rich. But Mary, far from disappointed, is so happy and grateful for what she has been given that Kimberly learns the true meaning of Christmas: It is not how much you get, but how much you love (Chapter Three).

The magazine I Love Cats printed the second chapter of Denery’s Secret Santa story in its December 1991 issue.

However enthralled you may be with this brief summary of “A Kitty Kat Christmas,” let me assure you, it is a terrible, terrible story. I don’t think I wrote it to be terrible, but it is, undeniably and objectively, terrible. I have no recollection what any of my colleagues thought about it except one—the woman from the job placement agency whose interest in ancient Egyptian theosophy led her to imagine the possibility of squashing people with her thumb like ants. For reasons never clear to me, she appeared in the office one day as our new receptionist and remained so for the rest of my time there. Perhaps she had discovered that being a receptionist paid better than finding people jobs as receptionists, or perhaps her tendency to transform placement interviews into reflections on the theosophical insignificance of pedestrians had compelled her superiors to suggest she find a new line of work. To this day, I regret never asking what precipitated her career change.

As I left work the day after the office holiday lunch, she stopped me. “Dallas, I loved your story!” I thanked her and was about to move on when she added, “You need to publish it here,” and showed me a copy of I Love Cats magazine. “You really think I should?” “Oh, yes, it’s exactly their kind of thing.” I read the magazine that night, and she was correct, “A Kitty Kat Christmas” was exactly their kind of thing.

The next day I mailed my story to the editor under my grandfather’s name, Percy Keegan. I received a response about a month later. “I have good news and bad news,” the editor of I Love Cats wrote. “We want to publish your story, but only Chapter Two. We will pay you $40.” I immediately accepted, although I did explain how this editorial decision undercut the true point of the story as Chapter Two, the dream sequence, merely sets the stage for the moral of the story (“It is not how much you get…etc.”), which only comes at the end of Chapter Three.

I also explained why, even though my name “really was” Percy Keegan, I needed them to sign the check to “Dallas Denery.” None of this received any response and, when the check arrived, it contained no additional correspondence. I was hardly surprised. This was the same company that published Quick and Easy Crochet—their plates were full. I remained a legal secretary for about another year, even after most everyone else—lawyers and secretaries alike—were let go after the firm lost its major client. But my time there was coming to an end anyway. I had started studying Latin through an adult extension program as I contemplated going to graduate school to study medieval philosophy, with the goal of becoming a college professor.

Unsurprisingly, being a college professor is not at all like being a legal secretary. Among other things, instead of writing stories about cats discovering the true meaning of Christmas, you end up writing essays about writing stories about cats discovering the true meaning of Christmas.

This, evidently, is what we mean by “scholarship.”

Professor of History and Associate Dean for Curriculum Dallas Denery II is an intellectual and religious historian who is interested in questions like “Why do we care about the past?” He has written a great deal about lying, including his most recent book, The Devil Wins: A History of Lying from the Garden of Eden to the Enlightenment, and—now—two pieces about kitty cats and Christmas.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.