Sixty Years of Song

By Bowdoin MagazinePiano instructor Naydene Bowder hits all the notes in recounting sixty years of teaching and learning through music.

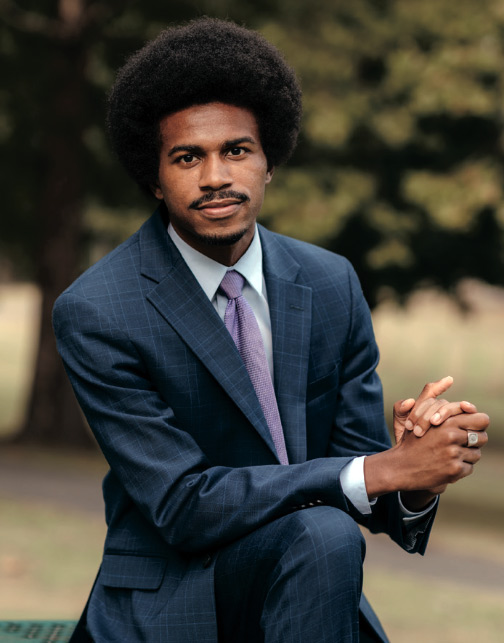

Naydene Bowder, who began teaching at Bowdoin in 1962 and is a charter faculty member at Portland Conservatory, has taught piano to generations of students. Photo by Jason Paige Smith.

Tell me about your path to music.

I think I was born to music. We can trace musicians back in my family to the 1300s in England. When I was two years old, my mom, who had played violin at Lincoln Academy, had me learning a song every week. She whistled when she was cooking, and she sang all the time. My father sung in his college choir and was very proud of the fact that he was able to hear Rachmaninoff when Rachmaninoff played in Chicago when he was on tour.

My grandfather knew he had to inherit the farm Down East, but he wasn’t a farmer. So, he decided he’d see the world while he still could. He was a fiddler, and he studied with every fiddler in every city he could find across the country—bought himself a really good violin and operated a cable car in San Francisco for a while. He came back East and met his future wife in Massachusetts while he was studying violin for a month or two there. She was a milliner who made very fancy, Victorian flowery hats, and she played the organ for her local church. They fell in love and decided to get married, but she wouldn’t come to Maine unless she could bring her upright piano, which weighed as much as an elephant. It had to come on a car pulled by four oxen on barges across every river to the family homestead in Bremen, Maine.

She told me a story that my grandfather put me up on the stool in the family room, took my two fingers and put them on E and G, and said, “When I stamp my foot, move your left-hand finger up a step to F,” and he took out his violin, and he started playing “The Irish Washerwoman.” When he went to change my finger, I had done it. So, he put me up on his shoulders and told my mother and my grandmother, “Ma, we’ve got a musician in the family!”

When I was two years old in 1939, my mother would take me to downtown Portland to WGAN, where they had a children’s talent show. Every Saturday, my mom would take me on the streetcar from Woodford Street, and I would sing a new song on WGAN. Somewhere in a trunk, there’s an old recording of me at two years old singing, “Climb up my rainbow, slide down my cellar door, and we’ll be jolly friends forevermore.”

There was a famous day when I was about four, when the daycare at our church Sunday school was closed and my parents had to take me to church with them. So off we went across the street to the old Woodfords Church, which had a wonderful Hook & Hastings tracker organ. So, I heard the organ for the first time, and I heard Bach played on it for the first time, and I heard the choir sing, and I heard my parents sing and everybody in church singing, and within a week or two, I refused to go back to the Sunday School. I wanted to hear the music. I became known as the little kid who stood between her parents and shared the hymnbook and knew the words and tune to every hymn.

How did you end up going to Julliard?

In high school, I was known as the girl who played the piano. I was the one who won the competitions—thanks to my dear teacher, who helped my parents pay and gave me so much more than an hour a week. She would make up every excuse in the book to see me three or four hours a week. You do not turn out a good musician on an hour a week. This is a daily workout thing that you need, and you have to decide, do you want it or don’t you?

I had a Maine accent forever. My first day at Juilliard, I was in the lunch line, and there was another girl in front of me with saddle shoes and a plaid skirt, and I was behind her in saddle shoes and a plaid skirt, and everybody else was in concert black with high heels and looking very Manhattan-y. We looked at each other, and we started talking, and she said, “You sound like a Maine lobsterman,” and I said, “You sound like the Kennedy family.” It turned out to be Dianne Goolkasian Rahbee who was a wonderful composer, and my students have won competitions all over the world playing her pieces. She was a forever friend.

What happened to get you started teaching at Bowdoin?

I was home in Maine in 1962 after getting my bachelor’s degree, and the University of Southern Maine asked me if I would teach a few of their students, because they didn’t have a music department then. And then Bob Beckwith from Bowdoin said, “You know, I’ve got two or three boys down here who want to continue piano. Could you come and give them lessons once a week?” So, that’s how it started. I taught part-time for Bob Beckwith for two years, and then I went to Hartt College for graduate school. I was fascinated with early music and the harpsichord.

My early teaching at Bowdoin was “classical,” just like the courses that were offered at the time. There’s a huge difference between Bowdoin before the ’70s and Bowdoin after. It’s been chaotic, but it’s so been extremely colorful—we don’t just have red, orange, yellow, blue, but everything in between, and we can mix and match as we choose. It’s just fantastic.

What kind of music do you listen to?

I always liked every type of music. What I listen to now mostly is what I think my students are listening to. I like to get into their world. If I’m by myself, lots of times I will listen to whatever I think Brahms was writing when he was going through some event in his life because I think I relate, as I get older, so much more to music without words, because it is a common way we communicate. I often say, “You can go to the grocery store and watch an adult who speaks any language from all over the world, and they have a little two-year-old in their cart who wants something. And you can hear this conversation between the adult and the child—it doesn’t matter what language it is. You know what the adult is saying and what the child is saying.” Our music goes back to prehistoric days.

What do you enjoy about teaching piano?

I very quickly realized that, to teach an instrument, you need to know your material, but you also need to know that every human being has a different body, and you have a sport to teach, and it’s got to be individually fitted and adjusted to that anatomy. And that anatomy is going to change with every year of growth, and you’ve got to relate that to every year of intellectual growth as well. I have friends who teach other things, and I hear them say now, “How can I reach students individually? My whole career has been teaching forty-five students at a time.” And I say to myself, “Oh, we people in the arts, aren’t we lucky? We have been taking material and adjusting it to each individual we work with our whole lives.”

You seem so young in every way—what’s your secret?

I remember, with a couple of buddies from middle school, when we were in Girl Scouts together, wondering if we would live to be sixty. Later in life, I thought, “Oh, you know, the secret is being able to look at things in a different light. I look at musical styles in a different, all-inclusive way. It’s time I started looking at myself that way.” That was a new discovery. I love teaching children, because you don’t have to tell them that every day is a new discovery.

I always thought, “Make the most of it,” you know? I feel like a child. I hope I never grow up. Because I would wish for every student I teach, for every child I raise, for every person in the world, to find what they love. Love is what it’s all about. Find what they love to do, and find a way to do that, no matter how they earn their living, because what they love is not limited. If they love music, they can whistle while they’re doing the dishes like my mother did.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.