A Toolbox for Floods

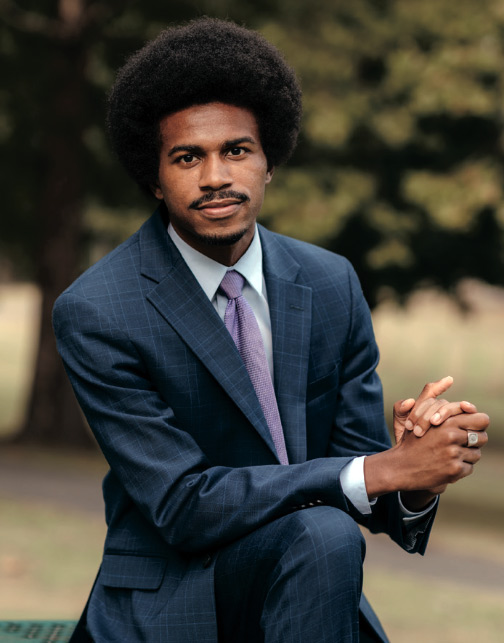

By Scott Hood for Bowdoin MagazineSam Brody ’92 arrived at Bowdoin dreaming of writing novels, but a single course changed his path—now he is a professor at Texas A&M and an expert on flooding and resilience.

Sam Brody ’92 is a professor at Texas A&M and directs the Institute for Disaster Resistant Texas. Photo: Ben Sassani.

Bowdoin: You came to Bowdoin thinking you’d be a novelist. How did that change?

Brody: As a kid, I had a love affair with Maine, and when I decided I was going to be the next great American author, my English teacher in high school said, “Well, you know, Bowdoin College is where Hawthorne and Longfellow went.” And I was like, “I’m doing it.” I never told anyone this, but I found out about Bowdoin because the lacrosse coach was recruiting me, out of Maryland, to play for the team, which I never did.

So, I’m gonna go to Bowdoin, and I’m gonna be the next Hawthorne or Longfellow. Two weeks into my first year, I decided I probably wasn’t going to be the next great American author. I probably didn’t have the talent. And then, I took Environmental Studies 101, taught by (Associate Professor of Earth and Oceanographic Science Emeritus) Ed Lane, and that changed my life. Whatever he said inspired me that this is what I wanted to do. So I pivoted early. I’ve written books, but not those kinds of books.

Bowdoin: What did Bowdoin give you that carried into your career?

Brody: For me, Bowdoin was about the place and the landscape, and that environmental studies major gave me more access to the surrounding area. I could really explore and learn about the physical environment and human impacts. I had some great, inspirational teachers and mentors—Ed Lane being one, and Evan Richert, who was the state planning director.

They got me to where I am today. In some ways, I’m doing the same thing I did as a nineteen-year-old—it’s just more sophisticated and statistical now. Society has caught up with the issues I was interested in back then. It’s of paramount importance to understand how to reduce the impacts of flooding in coastal and inland areas.

Bowdoin: Why was the Hill Country flood in Texas so devastating?

Brody: It’s a symptom of what goes wrong in this country—putting people and structures in harm’s way. Knowing or ignoring the risk. There were communication issues and warning system issues, but the fundamental problem is putting those cabins, and those people, in the most flood-prone area in a flood-prone region.

It’s the same problem as paving and developing in Houston, where we had the largest urban flood event in U.S. history in 2017. It’s the same as loading up risk in Southeast Florida on the coastline. It’s really where we put the built environment without accounting for the risk.

Bowdoin: You’ve said media work is important for you. Why?

Brody: I decided early on that it’s really important to talk to the media, and I enjoy doing it from an educational standpoint. During Hurricane Harvey, I wanted to check on our neighbor and rescue this person, and my wife looked at me and said, “You are not someone who’s going to rescue. Go talk to the media. That’s your job.”

And she was right. I gave dozens of interviews, and I’ve continued ever since. Scientific articles get peer readers, but media lets me tell the story to millions. It’s a way to create awareness and talk about these fundamental problems.

Bowdoin: What role do natural systems play in mitigating floods?

Brody: I’ve done decades of research on wetlands. Freshwater wetlands are the best naturally occurring flood mitigation devices out there, better than anything we can construct. I’m a big proponent of protecting natural wetlands—not just for habitat, and water quality, and esthetics, but specifically for flood mitigation. When we alter a wetland, we’re not just giving up storage. We’re replacing it with parking lots and rooftops that accelerate runoff into downstream communities.

Bowdoin: Are FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) flood maps reliable?

Brody: The 100-year floodplain map is supposed to show where there’s a one-percent annual chance of flooding. But in urban areas we see an unacceptable percent of impacts outside that boundary. In Houston, more than half of insured claims are outside the FEMA map. Nationally, it’s about a third. That’s why we created “Buyers Aware.” It’s like Zillow meets risk. You type in an address, and you can see your flood or fire risk in a simple format, plus what you can do to mitigate it.

Bowdoin: What about rebuilding — what should communities do differently?

Brody: The big problem is we rebuild the same thing in the same location and expect a different outcome, which never happens. Each community has its own characteristics, but the toolbox is the same: avoid, resist, accommodate, and communicate. Avoid the highest-risk areas. Resist with structures like levees or reservoirs. Accommodate by letting wetlands or parks flood. And communicate risk clearly, so people actually understand. Too often we just throw in a new warning system that gives false confidence and spurs more risky development.

Bowdoin: You’ve also been back in Maine recently, helping shape policy after major storms. What did that mean to you?

Brody: It was full circle. At Bowdoin I studied Merrymeeting Bay, looking at how towns’ plans and policies affected the ecosystem. Decades later, I came back to work on the governor’s commission and helped write Maine’s “Eye of the Storm” report. I was applying the same regional thinking I first learned as a student. Some of the very people I learned from were still around. It was surreal and deeply rewarding.

Bowdoin: Are you optimistic about society’s ability to deal with these issues?

Brody: I am. After Hurricane Harvey, Texas said enough’s enough. They poured billions into resilience and passed some of the strongest disclosure laws in the nation. If it can happen in Texas, it can happen anywhere. We still move in the wrong direction sometimes, but I’ve seen wonderful changes that make me hopeful. I’m surrounded by amazing people, and I feel like I’m part of something bigger than myself. That keeps me positive.

Bowdoin: Going back to the Hill Country flood, you mentioned systemic issues. Can you expand on that?

Brody: Beyond the cabins themselves, it’s about development patterns. Upstream building changes stormwater drainage, increases volume and velocity downstream, and worsens flooding. No one talks about the development around the Guadalupe upstream, but it exacerbated the downstream flows. You see the same problem in Asheville, North Carolina, where ridgelines are being developed. It’s the same issue repeating, creating compounding losses. Our institute tracks losses back to the 1970s. The trend is up, up, up. My job is to figure out how to change those trend lines, so they go down.

Bowdoin: So, it’s not just about better models or maps?

Brody: Right. We tend to think the solution is a better physics-based model. But the problem is systemic. I tell people: it’s not just where the water goes, it’s where the impact is. That’s why we’re developing statistical, machine-learning approaches and tools like “Buyers Aware.” And it’s not just about science—it’s about communicating risk in a way people can act on.

Bowdoin: How do you reach people when the warnings are often ignored?

Brody: That’s one of my biggest worries. I get severe thunderstorm warnings on my phone every week. Most of the time, nothing happens in my neighborhood. People get numb. Then, when the real danger comes, they ignore it. That’s why communication has to be precise and trusted. If a new warning system gives people a false sense of security, it can actually encourage more risky development. It’s not enough to have a siren or a text alert. The message has to spark response.

Bowdoin: You’ve said planning is about being proactive, not reactive. How did your years at Bowdoin shape that view?

Brody: Ed Lane sent me to look at all the town plans around Merrymeeting Bay in 1989. That was the pivotal moment of my intellectual life. I realized ecosystems cross jurisdictional boundaries, but planning often doesn’t. That fed into my master’s, my PhD and my whole career. I still teach my students to think regionally. One land use in a small town can affect a bay or watershed just as much as a big city can. That lesson came directly from Bowdoin.

Bowdoin: What has it been like to bring those lessons back to Maine?

Brody: Honestly, it felt like the universe made sense. Maine asked me to write an “Eye of the Storm” report after their winter storms, modeled on one I wrote for Texas after Harvey. Coming back to apply what I learned as a student—with some of the same people still around—was surreal. I also worked for Angus King’s administration years ago, and now I’m back helping on infrastructure and resilience. It really has come full circle for me.

Bowdoin: What keeps you motivated?

Brody: Partly, it’s my students. I’ve seen them inspired the way Ed Lane inspired me. One of my first, Wes Highfield, came up to me after class and said, “I don’t mean to bullshit you, Dr. Brody, but this is what I want to do with my life.” He’s been with me twenty-four years and is now a senior research scientist. Passing that torch keeps me going.

Bowdoin: After all these years, do you still feel the same urgency?

Brody: Yes. Every day there’s a new disaster in the paper. When I was in college, my mom would say, “What is this water stuff? You’ll never get a job.” She was an English professor. My dad was a construction worker. Looking back, it took courage to follow my own path. Now, unfortunately, the world has caught up. Flooding, drought, fire—these aren’t abstract issues anymore.

Bowdoin: Sounds like resilience is more than a policy buzzword for you?

Brody: Absolutely. Resilience is being able to accommodate impact and still survive. Sometimes that means moving your valuables upstairs. Sometimes it means raising a house nine feet off the ground. It’s not always glamorous, but it’s practical. And it’s essential.

Bowdoin: And the novelist dream?

Brody: I want to write historical fiction when I retire. For now, the stories I tell are about floods, resilience, and how to build a safer future.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.