Worst Club, Best Members

By Bowdoin Magazine

Are there people who don’t understand why you founded an organization called Sad Dads Club? Earlier generations seemed to feel the only way to manage grief was to not discuss it.

ROB: I would say few people don't understand why we're doing this. There are more spaces created for people to be vulnerable and open now—that generational shift seems as though it happened suddenly. I don't know what to attribute that to, but people are far more willing to show up and to be sources of support to other people who are vulnerable, especially when they can connect on something so tragic and so traumatic.

I would say in my generation, and definitely in my parents’ generation, it was considered that the only way to manage yourself emotionally was to not discuss it.

JAY: Shortly after we lost Bella, there's a woman who was I think in her early nineties who we'd see out in our neighborhood in the East End. Elly was very pregnant, and a couple of weeks later she saw Elly walking with our son and me and said, “Where's the baby?” We said, “She died. She was stillborn.” And we were heartbroken, and she said, “My husband and I lost one of our children. She was stillborn, and my husband didn't talk about it from that moment, through the day he died—never spoke of her again.”

And that was interesting, but not surprising. One of the first pieces of press we got was when Elly and I were in the New York Times talking about being a parent after losing a baby, and how it's still hard to be a parent. There are things that your living children do that drive you crazy, and there's this guilt associated with complaining about parenting. I mentioned how we had started Sad Dads Club in passing in that piece, and what people reacted to is the fact that a group of men were doing something for their mental health. That was still a novel idea just in the last couple of years.

That’s the reason that, more often than not, the members of Sad Dads Club, the other sad dads, we’re the first people they've ever talked to about this. Whether it's because it happened very recently that they lost their child or because they haven't had another outlet for this. There is still this reluctance. I don't know if it's a stigma or just a reluctance or hesitation among men to not necessarily talk about emotions.

There's still this reluctance among men. And, frankly, even your best friends, if they haven't been through it or experienced a close loss, it's often hard for them to empathize and to offer just that open ear. Rob and I talk to grieving dads all the time about this, and I still don't know what to say when someone loses a child. It’s heartbreaking. It’s the most awful experience any human can go through. I think there are a lot of factors at play. I know that our generation is more open to talking about mental health, which is incredible, but in general I don't think men are as far along on that spectrum as you may think.

Do you think the world treats sad dads differently than sad moms? You've been talking about it like a reluctance on the part of men to share their emotions, but is there also a barrier to that?

ROB: I think there's a historic stereotype that men to be strong have to be unexpressive and steadfast in their ability not to show emotion. We're finding that not having the opportunity, the invitation, or the outlet to talk about things you're struggling with in your mental health and your emotional state is going to be detrimental down the road. It will erode you from the inside, and it will present itself later in a destructive way, whether to yourself or your family.

I think that we’re, in a way, trying to redefine a bit of what masculinity is, that there is nothing that isn't strong and unbelievably profound about being a man who is in touch with your emotions. And that being sad, upset, confused, lost, angry, and crying—those aren't signs of weakness. They’re a sign of strength, of being really in touch with what you're feeling. Crying, that's a release. That's an expression of emotion. And that emotion is in there inside you somewhere, and if you don't have an opportunity, invitation, or an outlet to release it, it's not going to just go away. It's going to compound inside of you.

To Jay's point, men just don't have the opportunity unless there's a dedicated space to talk about this with people who invite those stories and invite those testimonials of feeling awful and terrible and not okay and sad and depressed and anxious and really struggling with a profound loss. I think that maybe men are treated differently.

That might be a stretch. I just think that it's been largely ignored, because of this expectation and this standard that men are “strong” and that when dealing with something emotionally difficult men can just grin and bear it, or whatever other saying there is out there to suggest that men just carry on without letting a traumatic life experience weigh on them in any shape or form whatsoever. Within our spaces, we're trying to say that we can be as vulnerable, as emotional, as we want to be, and that is actually a good thing. That's okay. That's welcomed here. And that is going to help you.

We don't have a cure for anything. We are a peer-to-peer nonclinical space. We can't say, “Do this and you'll get better,” because this is something that you carry for the rest of your life. So, I think the sooner people realize that men, women, no matter who is experiencing a profound loss in their life, this is something you're not going to get over, you're going to live with. And maybe there is a bit of a different treatment for men or an expectation for men, but I also think that's being redefined. That's certainly something we're trying to do our part to recontextualize.

JAY: And Rob and I and Chris, we started this very selfishly. We felt like we needed an outlet. Initially, we were very focused on our wives, and appropriately so. In the immediate aftermath of our losses there's not only the emotional strain for our wives, there's also the physical recovery from giving birth. And we wanted to protect our wives and help them start to recover. As Rob said, there is no getting over or getting through this. It's just learning to navigate life in a different way.

I know I didn't tend to my mental health in those early months as much as maybe I should have, because I was trying to protect Elly and make sure that that she could focus on physically healing and then starting to piece life back together. I think with grief in general, it's like, oh, that person in your life who passed away, that was like, three, six months ago. You're good now, right? And I think there's just this added element when you lose a child of just deep, unsettling grief. It's not the natural order, right?

Society has a tendency to just move on. It's often at that six-month point, when the meal train has stopped, when people stop bringing flowers and all those condolence notes stop coming. That's when you really need someone to talk to. As Rob mentioned, we’re non-clinical. But all three of us believe very deeply in, and our spouses do as well, the power of professional mental health counseling. So that's another key pillar of what we're doing: helping sad dads access professional care. And that’s how we all—I'll speak for myself—literally survived the immediate aftermath by going two, three times a week. But it gets expensive.

There is a huge vulnerability for marriages with this type of loss. How do your wives and partners feel about your work?

ROB: Nothing but resounding support in understanding and encouraging this space created for men. It is such a scarce, I should say nonexistent, commodity. There is nothing else—and we have looked high and low—that is community-based for men who have experienced a profound loss to go share stories and get peer-to-peer support. There just is not anything else out there.

That jarring statistic—last I heard was that 80 percent of marriages or relationships end after going through the loss of a child. Within our community, it will be interesting to see if this is something that can help save relationships, if a dedicated space where men can be emotionally expressive can help them return to places in their own lives where they are needed to show up, like in their marriages, with their living children, within their careers.

Can you talk about the differences between My Child, My Story sessions versus the open hours? What do you hope to achieve with that variety?

ROB: There are dads in our community who are in different stages of their grief journey, and the grief journey and healing journey are parallel, but they are nonlinear. And the more that our community has continued to grow, Jay, Chris, and I have recognized a greater need to have different spaces that make room for different conversations.

One Thursday is our Sad Dads Open Hour, which focuses on a theme that we'll announce ahead of time on Instagram just so that folks know if this is something they want to engage with, they can make sure they're there. Or if it's something they feel as though, that's not right for me right now, or they don't have an interest in it, then they don't show up.

At Sad Dads Open Hour, we pick a theme, and it's an open discussion. The alternating Thursdays are called My Child, My Story, which is an opt-in series where a father will sign up to share the story of their child and their family in long form, uninterrupted. That one came about when our group started growing more and more. We use the hand raise features and other things in Zoom to indicate when people want to share, and dads would be getting into really intimate and important nuanced details of their story that they clearly never shared before and then they'd see all these hands raised and they'd kind of snap back in and say, “I’m so sorry I’m going on for too long. I should pass it on to the next person.” So, this was our way of thinking, how do we create a space where somebody can get into these really important details of their story and not worry about who else is waiting to speak or any sort of time restraints? And as soon as we opened up this opt-in series—we were unsure exactly what the response would be—it booked out for over a whole calendar year.

I saw that. You've got people scheduled all the way until Christmas.

ROB: It was incredible to see that sort of response, and it's been even more incredible just how people respond, not only the folks who are in attendance listening and the environment that they create for the presenting dad, but we've started asking dads afterwards to provide a testimonial. How did you feel leading up to it? How did you feel during it? How do you feel after it? And overwhelmingly, they're just like, “This is the first chance I've had to ever go back and say this incredibly difficult story out loud,” and that they felt a physical weight lifted from them. They were getting better sleep.

It really is this unbelievably healing experience. Not only that, but for the folks who are in attendance, listening, they just get to know that child and that father even better. It’s been profound. It's been amazing. It is really, I think, one of the coolest and most healing things that that we do, and it's been awesome to see it have such a positive effect on the dads who have participated.

JAY: And if I can just add, Rob, I think one of the important pieces. Rob and I are best friends. We were college roommates, in each other's weddings, we've known each other forever. We went through each other's losses; we both live in the Portland area. We've talked at length about each other’s families’ losses. We know each other better than most people.

And there were anecdotes and heartbreaking details that Rob shared in that forum that I had never heard him share. Even if you have the best, most supportive friends and family, you don't often have that opportunity to just tell the whole story without something else coming along and interrupting. It's just this very intimate space that is really powerful.

And the fact that people show up. They want to be supportive, they but also just hear other people's stories and know where the overlap is and try to find meaning in those similarities to be able to help navigate their grief journey. This is what's so powerful, the support from the community.

Rob, you’ve written about having a strong desire to acknowledge and remember Lila. What does that feel like?

ROB: This is a difficult one only because what works for me is not going to be the same for someone else. And then it also may be exactly the same for somebody else. Just because of my place in life and because people saw a wedding ring on my finger, they would ask if I had any children.

This could be complete strangers in the checkout line at the grocery store. This could be someone, a colleague or somebody that I just happened to meet, a friend of a friend. It's just an innocent question that people ask. And in the immediate aftermath, I would say, “No, I don't have any children.” And even by the time Dallas came along, who's my living son, people always ask, “Do you have any more?” For whatever reason, when you have a single child with you, it's a natural thing to say, “Do you have any more children?” They're not like, “Oh, I see three with you. Did you leave any outside in the minivan?”

I would often answer no. And I personally would feel something physical inside of me tighten. When I changed that, when I started bringing her up at every possible chance that she could be brought up, it made me feel better. And this happened yesterday at the playground when I was watching Dallas and another parent came up to me and said, “Do you have any more children?” I said, “Yes. His sister passed away over six years ago.”

This is not me wanting to make somebody else feel uncomfortable. This is me putting what I need first, which is any opportunity that I can talk about Lila, I will take, and I will make her a part of the conversation. But we also have dads talking about the fact that, a stranger at a playground, they don't want to get into that. That's such a wildly personal detail of someone's life, and it's entirely reasonable to not want to share that with someone. That's another element of the magic to the connections within our community and the ability that we have to share what has worked for us while also acknowledging and creating a space where others can have a completely different approach that works for them.

There's no right or wrong. It's just about really acknowledging what you need to give your heart, and what you need to get out of your head, what feels necessary for you in those types of situations.

JAY: We're open to any fathers and non-birthing parents who've experienced the loss of a child, so that goes from miscarriage through the loss of living elementary school children, but what's unique about stillbirth is that the broader community doesn't have those memories of your child. And they don't necessarily want to ask a question that could potentially ruin your day.

When someone says, “Oh, something happened that made me think of you and Bella and Elly and your family,” that puts a smile on my face, just to know that other people are thinking about Bella. And we talk about Bella with our living children, and we honor her, celebrate her birthday every year, which is also the anniversary of her death. That’s really confusing and challenging to navigate. There are dads who will talk about how when they go to Starbucks to get a coffee, they'll give their child's name for the order because they want to hear somebody else say their child's name. Because it doesn't happen.

People ask about Jack, Pepper, and Sunny, our living children, all the time. We hear their names all the time, but you don't hear Bella's name as much. I think grieving parents are just often yearning for that opportunity to discuss, to hear their child's name. Getting back to the My Child, My Story piece, that’s one of the reasons that's so powerful.

How many members do you have?

JAY: It's thousands globally. I think what’s really powerful is that it's not just about the dads who are actively engaged. In any given week, any given session, there could be fifty-plus dads on a Zoom call.

But, when you look at our presence on social media, which we've grown organically, no paid growth, we’ve been intentional about that because we wanted people to be engaged who really want to be engaged. And while a major percentage of the group are sad dads, there's also a big segment that are loss moms, that are grandparents, aunts, uncles, friends for whom the posts Rob does on an almost daily basis strike a chord with.

Our Instagram posts also open a window into what we're going through so that those friends and other family members can just better empathize. It really provides this window into what we're all navigating. As Rob said, it’s nonlinear. Bella passed away over seven years ago, but yesterday was Mother's Day, and that's still a really, really hard day for our family. As much as there's a lot of joy—we have three living children, two rainbow babies who came after Bella—there's still just the sadness that Bella's not with us. I don't know that our family here will ever feel complete not having Bella with us. There’s this journey that ebbs and flows. And so, I think for people who aren't necessarily sad dads, per se, they engage with us sometimes. We’ve had people who joined sessions just because they want to know how to be a better support network for the loss dads and loss moms in their lives.

What's your diversity like?

JAY: That's actually one of the pieces I'm most proud of. It's just like Bowdoin. Sad dads come from all walks of life. Geographically, there are dads from across the US and Canada and as far away as Europe, New Zealand, Central America. It's incredibly diverse in socioeconomic backgrounds. We haven't done an official survey, but race, it's very diverse.

We have dads who are scientists, who work in business and technology. We have a professional football player from the Midwest and teachers, firefighters, police officers—dads I would never have met in any other context.

Some of the sad dads must also be angry dads. How do you deal with that as a group when that happens?

ROB: We very openly talk about anger and our hope, I think, in doing that is that the conversation naturally shifts to ways that you can productively and safely deal with and change that—“change” is the wrong word, I should say that you can redirect that emotion and you can acknowledge it. We are never about ignoring what somebody genuinely feels, but we also want to make sure that we, to the best of our ability, again, we reiterate that we are a peer-to-peer, non-clinical space. What we do should never replace or be a substitute for professional mental health services.

But what we've experienced in being able to speak openly about anger is it doesn't present as violent, it really just presents as an acknowledgment of feeling mad at the world and not really knowing where to go with that emotion or what sense to make of it. Because it doesn't make sense, because it's coming from something that you never saw coming, that frankly isn't fair, no matter who it happens to. Nobody deserves to have this happen.

And our community has just done such a good job of holding a space that is one of support, validation, and warmth that I've only seen dads who have expressed how angry they feel—and this can take hours for us to talk about and talk through it—that it then results in them feeling as though, okay, I have acknowledged that. I'm now moving. I am moving in a way that redirects that anger into something else, whether that's exercise or art, some sort of release that is not going to be damaging to the individual or to anybody around them. The environment in which Sad Dads Club operates naturally brings people to saying, “Yeah, I felt that too. I felt really pissed off today. I actually felt really pissed off for the last month. Anger has been an overwhelming theme and feeling that I've had and it's really uncomfortable and I'm not sure what to do with it.”

And having somebody across the proverbial table from you saying, “You know what, I felt that too, here's what I did.” And then somebody else saying, “I also felt that” or “I have been feeling that way.” It naturally quells that uncomfortable and nearly uncontrollable feeling of anger. I think that dads come out of our sessions feeling better, feeling as though they've had a release, whether they're listening or contributing.

There are some dads I've never heard say a word, but I see them on screen every single week, and they get exactly what they need out of that space. And we have a Discord channel, which is a free app on which we have a private Sad Dads Club channel. There are over 130 dads who are active on that channel and that is active 24/7. So, I think that shows there is a desire to stay connected and engaged and where we see people getting that peer-to-peer support in moments of anger, in moments of confusion, in moments of hopelessness.

What’s next for Sad Dads?

ROB: We recently identified our pillars for fundraising, what our fundraising priorities will be, and the two things are community building, which is something we're actively doing now, and the second pillar and the one that will require the greatest dollar amount to achieve is removing logistical and financial barriers to professional mental health services.

Within what our community does right now, that peer-to-peer non-clinical space, we can absolutely provide that, but we cannot provide professional mental health services because none of us are professionals. All three of us, Chris, Jay, and myself, we all benefited immensely from grief services from a professional therapist. And we all were extremely lucky to be employed at organizations that had good insurance, and that in turn gave us access to high quality professional mental health services.

And that's just not the case for everybody out there, and it is such a crucial component to healing and grieving that we want to make sure that we remove that disparity, so that a family's ability to pay and where they work, that's just not a factor. We want to remove not only the financial barrier, but also come up with a system that removes the logistical barrier as well. For a father who's in the immediate aftermath of their loss, executive functioning is extremely difficult and potentially just nonexistent.

Having to sift through potential therapists, especially ones who specialize in the loss of a child, is so overwhelming that the grieving parent often stops looking. To be able to remove that by having a network of professional therapists who specialize in infant and child loss is going to help people get access to that crucial component.

It is just so, so vital. It really can't be overstated how crucial to our healing journeys that was. As Jay said, it was lifesaving. I would agree. I didn't know what to do.

JAY: Tragically, the rate of stillbirth in the US is one in 175, which equates to 21,000 babies per year. And it’s 1.9 million stillbirths globally every year. I work in the business world, that's what we’d call a big TAM, total addressable market. We wish it weren't the case, we wish it was zero, but that's not the reality. So, we want to be able to reach all those sad dads not just in the US, but around the world.

We talked about how our core sessions are 8:30 Eastern time on Thursdays. But that means that we have dads joining at three o’clock in the morning from Paris or late on Friday afternoon during the workday from New Zealand. So, to be able to offer these sessions to more dads in more convenient time zones, and there's just the three of us. Rob has gone full time as our executive director and leads those sessions, but we need to be able to find ways to replicate that and to bring more trained facilitators into these sessions so that we can reach more dads.

We have talked about potentially expanding to have a Sad Moms Club and having different kind of affinity groups, depending on the type of loss. We want to make sure that people feel as comfortable in whatever space and that they're able to get the most out of it.

We have dads whose children would be in their forties now, who were stillborn decades ago. We have dads who lost living children. People our parents’ age who want an outlet. We're focused on the core mission right now, but we want to expand. That's why we'll be launching a campaign—to provide access to quality mental health services that Rob discussed but also offer more sessions for more people in more time zones because there's clearly a huge demand.

Grief is obviously the connective tissue with you guys, but is there joy in this too?

ROB: That's exactly where the magic comes in, because there is. That's what makes the group uniquely special. That's what makes the community a community that people want to be a part of, and the people want to do everything they can to foster and to expand. We have dads who come to us all the time asking what they can do and wanting to do more, because not only do they feel as though it has given them so much within their grieving and healing journey, but they also know there are other dads out there who don't know about this.

How do we get it out to more people? How do we ensure that there is not a single dad out there who doesn't think there's nothing available to them? Because this group is it. It’s remarkable to experience and be among these dads who are able to laugh together and create connections that result in inside jokes. Where people have taken it a step further and started getting together in person. We've done it here in Maine a handful of times. People are doing it out on the West Coast, in the Midwest, all over the country, in Europe. We have our second retreat coming up at the end of this month, and it’s so joyful.

In our community we had always said it's our loss that brings us together. And one dad said recently, it's actually our children who bring us together.

And that articulated it in a way that was so much more meaningful and gave life to our children and a legacy to them that just felt and feels so good. We wouldn't know one another were it not for our children, and now we're able to share and expand and foster a space that celebrates them, that honors them. Moments can be sad, but more than I think anyone would guess it turns into a lot of laughs, like laughing until you're crying in a joyful way because these dads have become so close and so connected through their children.

It's magic. It is so joyful, and it is our children bringing us that joy. You would never believe that something that is rooted in a tragedy would become so joyous for so many people.

JAY: Rob talks about getting together in person, going to hockey games, going bowling, going hiking, going to a brewery, whatever. But we'll have dads who'll say, “Hey, I'm defending my dissertation to get my PhD. It's open to the public. Does anyone want to come?” And the vast majority of the people watching the dissertation defense are Sad Dads Club members.

One of the most heartwarming experiences that we've had is seeing dads who've gone from weeks out from losing their child to then having their rainbow babies and supporting them through that. Pregnancy after loss is a difficult rollercoaster ride of emotions. The excitement of getting pregnant is quickly replaced with anxiety about whether the baby will survive. Before losing a child, there’s that naivety of everything being rainbows and butterflies when you get pregnant. The stork shows up nine months later, drops the baby off. We know what the alternative is, right?

We're there to support each other through that journey, and are also the biggest champions for each other when that rainbow baby arrives. I'm getting goosebumps just thinking about it.

When new dads join, we have to remind ourselves as we're joking around with each other that this is also a really serious and sensitive space, so we have to be delicate with it. Rob, Chris, and I were so touched early on when a new dad said, “No, don't stop being fun. We want to see what we will be like in three, four, or five years, we want to know that it's not going to be this deep, dark depression all day, every day for the rest of our lives. Knowing that you guys have found joy again is really inspiring to us.”

It sounds like a cliché, but the power of the Bowdoin network is there whether you're networking for job opportunities or fun things, or in the deepest, darkest days. It's bonded us all.

The three of us are all very lucky to be married to incredibly smart, strong, successful Bowdoin alumnae. Without Bowdoin, I don't know that Sad Dads Club would exist.

ROB: Our wives are our absolute rocks and they made it possible for us to feel equipped to try to build this community. And Bowdoin is such a small and tight-knit community, but it's also everywhere. Bowdoin showed us what the power of community can be and how far spreading it can be.

JAY: And Chris, he’s an honorary Polar Bear. He was at least smart enough to marry one.

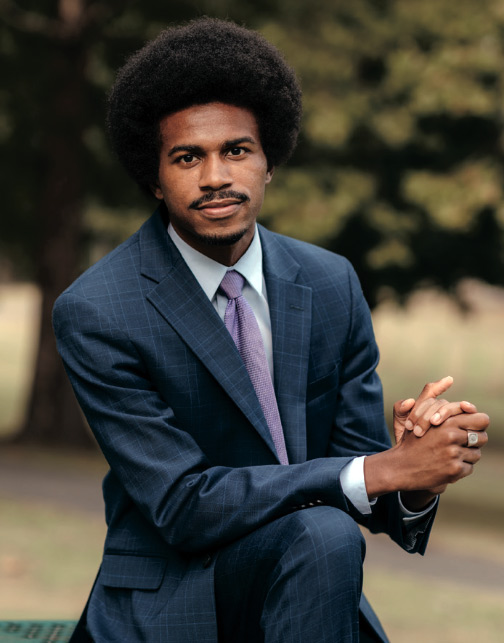

Rob Reider ’07 is a musician, dad, and the executive director of Sad Dads Club. Cofounder with Rob and Chris Piasecki of Sad Dads Club, Jay Tansey ’07 is a proud dad, husband, and technology executive at IDEXX.

This story first appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.