Words Sent to My Friend

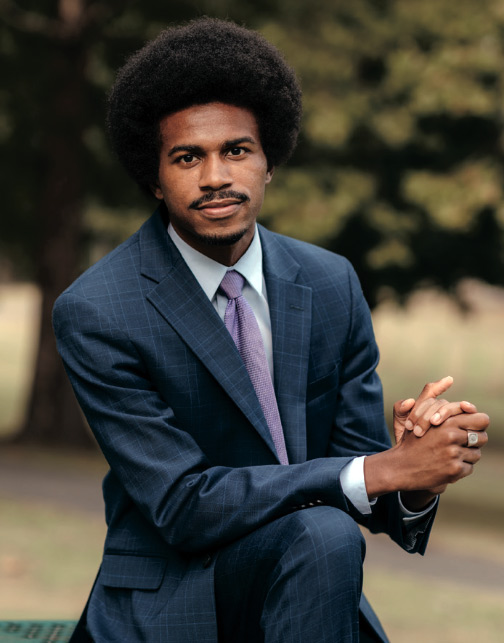

By Nora Biette-Timmons ’14 for Bowdoin MagazineNora Biette-Timmons ’14 reflects on the arrest of her classmate Evan Gershkovich and on risks to journalists around the globe.

“It's okay. I’m sad and sleepless but holding on,” Evan wrote to me on March 13, 2022. I’d messaged him on Twitter to ask how he was holding up following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—and to congratulate him on his new gig as Russia correspondent for The Wall Street Journal. The actual invasion had happened a few weeks previously, but I waited a bit to be in touch; I hadn’t wanted to bombard him in the midst of an already overwhelming moment. As I wrote to Evan in my message, I “figured everyone you’ve ever spoken to has been messaging.”

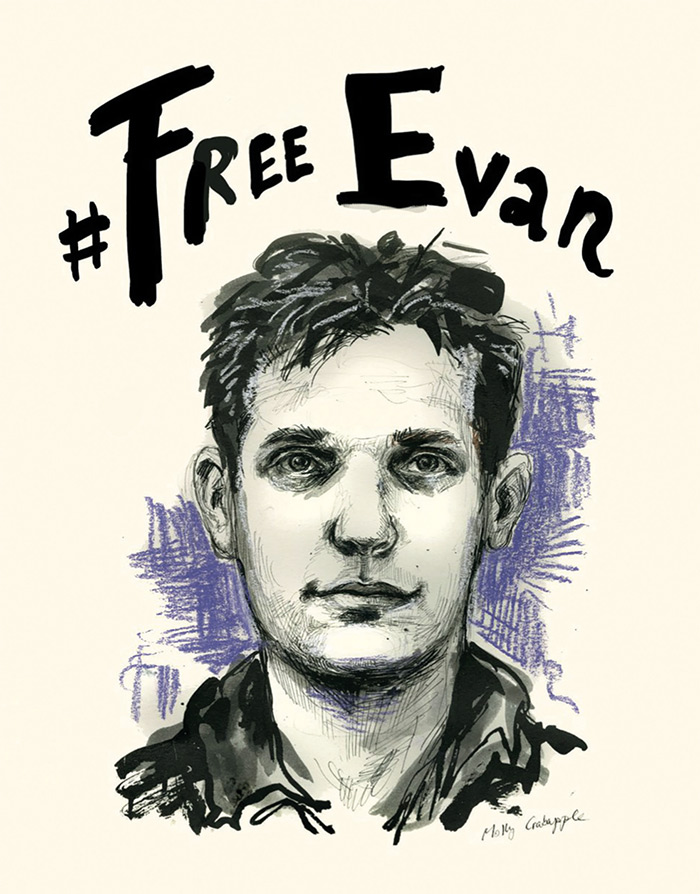

A year later, on March 29, Evan was arrested by the FSB, the Soviet successor organization to the KGB, while reporting in Yekaterinburg, a large Russian city east of the Ural Mountains, and our brief exchange last year feels eerily prescient now, as he sits in a Russian prison cell—physically OK, most importantly, holding on, likely occa- sionally sad and sleepless, receiving hundreds of letters from everyone he’s ever spoken to, and then some. That’s because, almost immediately, his friends from Moscow figured out a way to get letters to him in Lefortovo prison. The email address (freegershkovich@gmail.com) through which letters are sent to be translated and transcribed has frequently been shared by major media outlets, resulting in hundreds, if not thousands, of missives from strangers.

“On the actual day The Atlantic wrote about it, there were 592 emails,” Polina Ivanova, a Russia correspondent for the Financial Times, told me. She and Evan became fast friends in Moscow when they met a few years ago, and now she manages the email inbox, along with another journalist friend, a process she called “totally hectic.”

“We have it set up on our phones,” she said, and in the first three weeks after Evan’s arrest, she would get “a notification every five minutes.”

As of early May, roughly 1,600 individuals had written Evan emails, Ivanova said, and about 350 of those “are connected to Evan in some way”—friends, parents of friends, colleagues, other journalists. Some people write to him nearly every day, and Polina has been able to have multiple back-and-forths with him.

“He wrote in his first letter back that he has read the stories of political prisoners in the past who have said how much joy it brings them to read letters, but it’s a next-level happiness to receive those letters yourself,” she added, “which I thought was very poignant.”

I met Evan sometime in the fall of 2010, when we were first-year students. I don’t recall the moment we met, but then, suddenly, somewhere in that first semester, he appears in my memories. As plans for sophomore year housing fell into place, a group of our friends managed to stage a (ResLife-sanctioned) takeover of Ladd House, and the next fall, Evan and I were next-door neighbors, tucked away on an alcove hallway with two other friends and a shared shower. We remained close through college, and then our friendship took on new dynamics as we entered the world of professional journalism, trying to navigate the industry and commiserating over the evergreen uncertainties of early careers.

Now Evan, who had been accredited by the Russian government to work as a journalist, has been charged with “espionage,” which his editors at the Journal and the American government have repeatedly called baseless (and which I, as his friend of well over a decade, feel very confident calling utterly bogus). Rather, his arrest and the charges represent Russian president Vladimir Putin’s crackdown on dissent and on anything that falls outside the bounds of Kremlin propaganda.

Evan's case has made headlines across the world, in part due to its singularity. Russia had not arrested an American journalist operating within its borders since 1986, when U.S. News & World Report correspondent Nick Daniloff was arrested under similar circumstances and released within weeks.

But reporting in and on Russia has become a much trickier—and riskier—proposition in recent years. For example, in 2021, BBC correspondent Sarah Rainsford was kicked out of the country after reporting from Moscow for twenty years. She was given varying reasons, but her expulsion came shortly after she asked Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko, a strong Putin ally, how he could remain president in the face of widespread protest against his corrupt reelection.

Then in early March 2022, shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, Putin approved a law punishing journalists who print “fake” news about the military—that is, anything that counters the Kremlin’s party line—with fifteen years in prison. Critical news outlets were banned entirely, and multiple journalists were arrested under this law.

“Reporting on Russia is now also a regular practice of watching people you know get locked away for years,” Evan tweeted in July 2022. In a single evening in September 2022, at least eight journalists were arrested covering protests against Putin’s “partial mobilization” across the country.

But threats to journalists are not isolated to those reporting in Russia. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, the number of journalists imprisoned across the world has jumped from 92 in 2000 to 363 in 2022, with the second-largest increase coming in the last two years. Threats of doxxing (publicly sharing address and contact information) journalists, and actual instances of it, are not uncommon for those working on certain beats.

And the US has its own share of concerns. Out in the field, journalists are routinely detained while covering protests. Between 2020 and 2022, the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker logged 195 such incidents. In May 2020, a friend and colleague of mine at HuffPost was arrested while covering Black Lives Matter protests, despite his press badge on prominent display. At least five other journalists were arrested while reporting that same weekend.

Though these represented chinks in the armor of the First Amendment, they were all released within hours. Evan was not.

Like many of his friends, Polina has spoken to numerous media outlets about Evan’s case and recently began discussing how he’s keeping busy. He has access to a library and does lots of reading; he was making his way through War and Peace when Polina and I talked in early May. He also exercises, and “in the evenings, he tries to reply to letters.”

“He sounds very determined and focused,” she said, and he’s “still doing the thing where he cracks jokes, so he’s all right.”

This news soothes me, because it is the Evan I’ve known for over a decade, the gregarious goofball who makes friends wherever he goes, whose work ethic and ambition are outstripped only by his deep-seated curiosity—the qualities that, of course, have made him a good journalist.

But though it is heartening to hear the version of these updates—versions of which I myself have shared with journalists from The Washington Post to the Orient—Polina and I agree that they don’t come easily. It feels surreal and unnatural to be sharing snippets of our correspondence publicly, just as it feels weird to tell the BBC about the time we spent as next door neighbors living in Ladd sophomore year, or send CNN photos of us and a dozen other friends gathered side-by-side, arms pulling each other close, in various off-campus living rooms senior year; “family portraits,” we’d (semi) jokingly call them.

“We’re really conscious of it,” Polina said of sharing what would, in any other situation, be normal, private, utterly unremarkable correspondence between friends. “But at the same time it’s so important for people to get to know him, to understand him, to get to know his character.”

I’ve been scouring our past emails and messages since his arrest, and our conversations once veered from teasing about dating prospects to discussions of intra-newsroom dynamics and back again, all in one go. But my biggest takeaway now is the ease of it all—there is no email address, no translation and transcription needed; there are simply words, loaded with inside jokes and years of shared context, sent to my friend across the world, at the press of a button. I miss those days.

Nora Biette-Timmons ’14 is deputy editor at Jezebel. She previously worked at HuffPost and The Trace and was an editorial fellow at The Atlantic.

This story first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.