Moments with Dad

By Doug Stenberg ’79 for Bowdoin MagazineAn obituary can list the accomplishments of a man but rarely gets to the soul of his story, especially for the loved ones and friends he leaves behind.

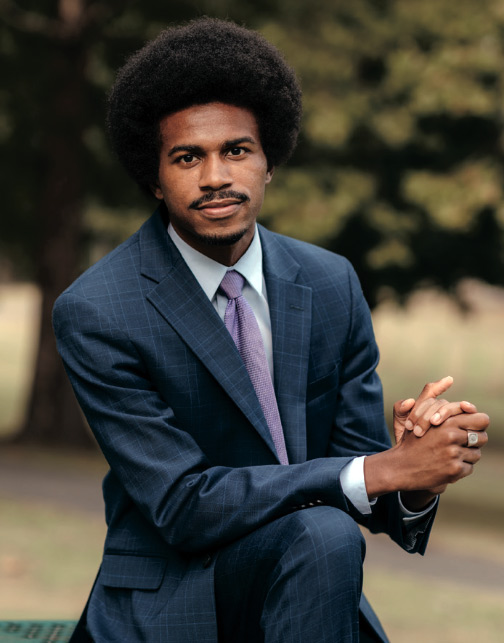

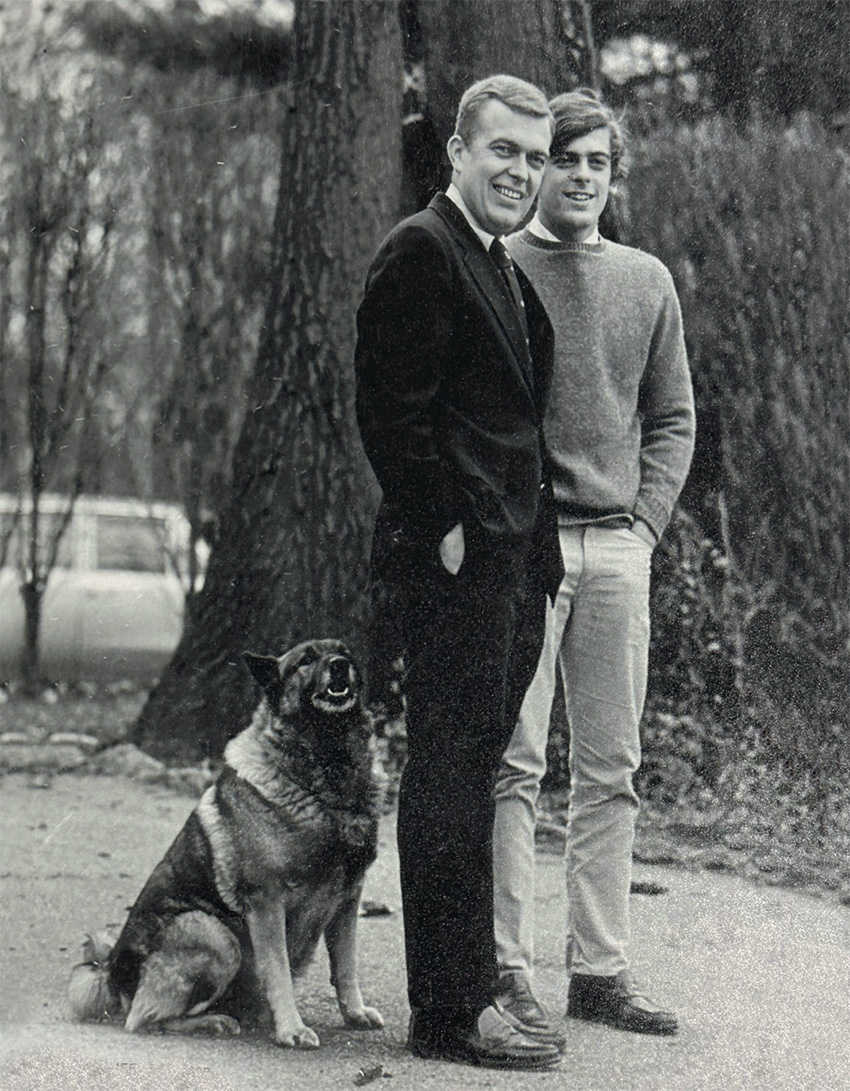

Terry Stenberg ’56 and his son, Doug Stenberg ’79, with their dog, Thor, circa 1975.

My father, Terry Douglas Stenberg ’56, was profoundly driven, and his accomplishments are formidable.

His 2,000-word obituary listed so many of them: His perfect pitch. Attending Bowdoin, where he was a Meddiebempster. Joining the military and rising to the rank of captain. A career in education, including twenty-four years as a headmaster—fifteen of them at Hawken School. A stint as director of the American Collegiate Institute in Izmir, Turkey, where he was diagnosed with colon cancer. Holding volunteer positions with various boards. Writing five major pieces for two different instrumental ensembles, including “Remembering Tilly.”

These accomplishments are in black and white compared to the technicolor memories I have of him—and of us, together. Reading a draft of the obituary the year before he died, I was reminded of how much time had been lost over the years, how many moments slipped through those lines. How many school evaluations, for example, did it take to make a life?

I wasn’t there for those, my memories hovering just around the periphery: The way he used to call out “Hi-o” when he came home from work, and my sisters and I would run to greet him. His returning home from active duty, and how I cried in his bedroom when I thought he might have to go to Vietnam. The faculty parties he and Mom hosted, where downstairs was full of upbeat cacophony, and I could make visits to the kitchen for chips and chocolate chip cookies.

The more vivid moments are the ones we shared together: Our unbridled joy when he taught me to ride a bike at Pine Manor. How happy we were when I got into Bowdoin, and how he consoled me when, having lost a wrestling match at sectionals, I was at the end of my tether physically and emotionally. The times a few years before he died, when we would drive down to get lobsters in Cushing or when we would watch a Red Sox game together. Or toward the end, sleeping on the floor of my parents’ living room and waking to the sound of a cowbell, which Dad rang to call for help. We held onto each other as we inched our way across the rug, Mom still asleep in their bed.

The most vivid, though, are our conversations. Over the years, we had many about our shared alma mater. In talking about Bowdoin, in some ways, Dad and I were talking about something very close to our hearts. Even when talking about what was currently happening at the College, we were simultaneously reaching back into the past and toward a future.

Bowdoin was a liberating time for him. His family of origin were Christian Scientists, and Bowdoin was the place where he chose a different path. The most definitive experience for him in many ways was touring US military bases in Europe with the Meddies. It allowed him to see the world in a brand new way.

I wonder sometimes if he had been wired differently or if I had been wired differently, if we could have had more moments like that, of natural, spontaneous closeness.

I rarely saw him happier than when he got together with fellow alums. I grew up listening to recordings of fellow Meddie George Wheeler Graham’s solo of “Ding Dong Daddy from Dumas” and Norm Nicholson’s sublime rendition of “The Lord Is Good to Me.” Other members—and aspiring members—visited us while I was growing up. One year, Bob Keay ’56— one of the aspiring members—regaled us with “Nature Boy,” as we sat around our large antique dinner table. We all broke out into applause—my dad the most enthusiastic of all.

Growing up, I picked up on what Bowdoin had meant to him. I originally was following his paradigm. I, too, joined Beta. I became a Meddiebempster. He was always proud of me for being involved in sports, and I joined the football team.

As the son of a headmaster, I was always very conscious of trying to toe the line. Oddly, failing a British history course while studying abroad in England was a crucial experience for me and allowed me to break away from his paradigm a bit. I failed history, but I took a course on a Shakespeare program in London. When I returned, I eventually did a two-man performance of Macbeth with Peter Honchaurk ’80 in the basement of Pickard Theater. Herb Coursen praised the production in Shakespeare Quarterly. I also focused on Russia to study the language and literature and then pursue grad school before becoming a teacher, in some way returning to the paradigm.

When he and Mom spent three years in Turkey, we communicated mostly by letters, except for when he was diagnosed with cancer. I was teaching in Seattle at the time, and I called him from a pay phone in a quiet café not far from the Northwest School. I told him that I loved him and that he would get through this, and the family would too. Mildly earnest patrons respectfully ignored me blubbering into the phone.

Life is all about mysteries and ironies. In the ’90s, we actually ran into each other at an airport somewhere in Germany—maybe Frankfurt or Hamburg. I was waiting for a connecting flight to St. Petersburg. Dad was running a school in Izmir or doing a school evaluation in Germany.

My memory is fuzzy on those details. What I remember clearly is seeing him sitting in a secluded gate that was mostly empty. I couldn’t believe it. I wasn’t allowed to sit with him, but we were able to be close enough to talk, and we had a good conversation.

I wonder sometimes if he had been wired differently or if I had been wired differently, if we could have had more moments like that, of natural, spontaneous closeness. I think he tried through his music. I tried through sharing movies. It wasn’t always easy, and communication wasn’t always consistent.

I called him for the last time on July 4, 2020. He was in hospice, and Nurse Diane held the phone to his ear. Apparently, he moved his hand at the sound of my voice. He couldn’t talk. I don’t remember much because I was just so conscious of knowing he was about to die and focused on the sound of his labored breathing. I’m certain I expressed my love for him. I know I mentioned John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, but I did not dwell on July 4th, fifty years after the Declaration of Independence was signed, when they both passed away. He died the next day. It’s very strange to think about that being a conversation, but it was still a form of communication. Of love.

I think sometimes that simple act of trying to have a conversation is the point. The Constitution was written to be a living, breathing document that evolves with us. Just like our relationships—if we make the effort for them to be ongoing and evolutionary.

It’s worth it to find the stories we didn’t know, such as a photo found over sixty years later of a father reading to a son, when his memories are essentially of his mom doing that. Or the recollection of a particularly difficult meeting with a board member, who, when informed that my dad had to meet with me at a certain time, said “Sons can wait,” and my dad responded, “Mine doesn’t.”

Reflecting back on our life together, there are plenty of things I wish we had both done differently. Now, I am able to more clearly see the outline of his life, and how for so much of his life he may have been trying to prove something to his biological father, Charlie McClain, who had been cut out of his life since he was four. He broke that paradigm for both of us. Though he had so much professional drive, I can’t say that I ever felt pressure from him. I felt more approval when I did certain things, but never pressure to achieve. Certainly, I was not like one of my classmates, who went on to be very successful but whom I found weeping in a dorm because his grades were average and his dad had said, “If you get four H’s, don’t come home.”

It’s all those moments—both remembered and discovered along the way—that get left out of the obituaries, no matter how detailed and impressive. They also happen to be the ones most worth remembering.

For roughly thirty years, Doug Stenberg ’79 taught in schools, colleges, and universities from Seattle to St. Petersburg, Russia. His favorite acting roles have been Macbeth, Caliban, Jaques, Feste, Bottom, and Scrooge. To read his father’s obituary, go to obituaries.bowdoin.edu/terry-d-stenberg-56.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.