Keeping the Tempo

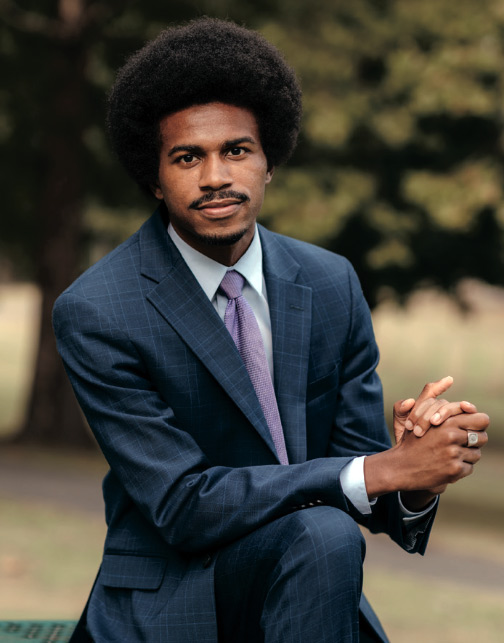

By Bowdoin MagazineAs the assistant dean for inclusion and diversity at Bowdoin, Eduardo Pazos Palma oversees everything from religious, spiritual, and cultural experiences on campus to evaluating and adjusting Bowdoin’s social pendulum with the cadence of tradition.

It seems there’s been a shift in the way people approach faith on campus. What changes have you seen?

In the last fifteen years or so, we have seen a huge shift away from Christianity and a big increase to agnostic or “not affiliated”—not in the atheism category. It’s evolving the way students understand religion and spirituality for themselves, but it is also evolving the place and function of religious and spiritual groups on campus. To a certain extent, it has helped the religious and spiritual groups on campus see the great cultural value that religions bring to the conversation around diversity and identity. For instance, this year we celebrated the biggest-ever Diwali event on campus, had a huge audience at lessons and carols for Advent, and our Hillel group keeps being one of the most active groups, and the Muslim Student Association has grown every year.

There is a sense in which religious traditions—I would argue traditions in general—often feel like home. They’re not perfect. There’s certainly a lot to tease out. But there is something about ritual. I think especially in times of crisis all of us crave tradition and ritual. That was one of the hardest things about the pandemic, that it took away. It wiped out all of our traditions, our weekly, our yearly, our semesterly gatherings. It wiped out the ability to do those things, and it left a lot of us feeling unmoored. Because these traditions and these celebrations and rituals, which often coincide with the sun or the moon or the time of the year, we lost those. Tradition is a cadence—it is constantly telling you the tempo—and we lost it. That was devastating for a lot of people.

On the other hand, we started to realize the role spirituality plays in holistic health. Spirituality can be an important source of wellness, and we’re starting to see that with the huge increase in the practice of yoga and mindfulness, meditation—loving kindness and compassion meditation. Those are all spiritual practices. You don’t have to practice them spiritually; there is a secular version of it. But they are grounded in spiritual practices. I think we have seen an increase in people going on retreats—a silent retreat, a meditation retreat, a walking retreat. Those are also spiritual practices. In general I think it is helping us understand that we can tell stories that are bigger than us, stories that give us meaning, and stories that help us frame this interconnectedness that we all have.

For some of us, I would argue that the interconnectedness extends beyond the human realm into the realm of this Earth and the planet. I think it frames this idea of eco-climate anxiety—on the one hand, we’re feeling it because we continue to harm our ecosystem and our habitat, and on the other hand I think it gives us a lot of source of healing and rest to be able to find ways to be connected to nature, to the ecosystems around us. I think we’re learning more and more that we are barely separated from the microbes on the Earth—in the water and in the soil. We are made of viruses and bacteria and microbes, and I don’t know how separated we are. We might be a lot more connected to even the tiniest, minuscule pieces of the Earth than we think. Whatever is happening to the Earth will affect who we are and how we see the world. I think of it like a fabric. A thread in one corner is not far removed from the other corner. They’re not next to each other, but if you tug at this side you’ll be tugging at the other thread. I find that deeply beautiful and inspiring. And a huge responsibility as well—to take care of each other and take care of the Earth.

You see often in the media the idea that to be a globalist or to seek a global future is somehow anti-nationalist or just bad. But students seem more interested in each other’s cultures than in previous decades. What do you think is causing that shift, if that’s what you see?

Across the country we are graduating from high school the most diverse class of students ever. And I think students have a very different understanding and appreciation for diversity than a lot of us had growing up. And I think that has changed in really positive ways and will continue to change probably for the next fifty or one hundred years.

An understanding of difference has helped us see that diversity is resilience. Diversity is an added benefit—it makes us better, it makes us kinder, and it makes us understand each other better. When you live in a diverse community, there are so many boxes there’s almost no boxes. Which I find so beautiful because it really allows for the authentic self to come through in ways that maybe other generations before didn’t fully get.

There is a divide in how people view the world, especially when it comes to diversity and globalism. Are we at Bowdoin looking through rose-colored glasses? Are we preparing students for others’ perceptions of reality?

That’s a question we often talk about in my world. Here’s what I know. We have incredibly intelligent, capable, and just amazing students who join this community every single year. And we have equally talented staff and faculty who educate them every single year.

An understanding of difference has helped us see that diversity is resilience. Diversity is an added benefit—it makes us better, it makes us kinder, and it makes us understand each other better.

This generation of students that is here at Bowdoin right now, every single one of them came of age during the Black Lives Matter movement and the murder of George Floyd. For them, they grew up understanding that, when the system is not working for us, we get together and we go out in the street and we protest, and we change things. And we change the way we talk about each other, the way that we legislate each other, and the way that we make things happen in our society.

Students are really aware of the social changes that they are seeing around them. When we create environments like we have at Bowdoin, where there is conversation and education and a plurality of ideas—that prepares you better than anything else to be able to go out into the world and to be able to experience this difference of ideas and to have the stamina and the resilience to encounter whatever it is that you’re going to encounter. I think having a strong base and foundation is one of the best things we can do for our young adults as we’re helping them to graduate into “the real world.”

When it comes to students, do you see empathy being extended to everyone?

I think social movements are reactionary, and they go on a pendulum. I don’t think it’s a perfect balance right now. Because the conversation in the last two or three years has been so centered around systemic inequalities, we could, I think, do a better job to have a bigger understanding of the way that all of us need to be kind, compassionate, and empathetic toward each other. I think that’s the goal of a lot of the work that we do in inclusion and diversity. It really is to center the dignity of every single person in our community. Every single person. It doesn’t matter if you and I deeply disagree on something. You as a human being are worth every single ounce of respect and dignity because that’s really what creates community in ways that create transformation and the common good for all of us.

Are there any cultural groups or segments that are kind of beyond the pale in that regard?

Two things: On the one hand, in order to be part of the Bowdoin community, all of us— students and employees—agree to abide by our nondiscrimination clause, which means that I cannot refuse to meet with you because of your identity. That would be in violation of our nondiscrimination clause. However, that doesn’t mean that you cannot have your own thoughts about ideas, policies, identities, or whatever it is that you want to have. It just means that, in order for us to act and to be in community, we are saying that we will not discriminate against each other based on identity. So, I think for the College, our desire to be an inclusive community is essential, and the fact that we all choose to be here when this is one of the conditions to do so, that means it’s a pretty good place to be.

But, to your question whether any one of us is beyond the pale, I think every single generation across time has experienced extremism in one level or another. Can we eradicate it altogether? I don’t know.

Optimistically, I would want to say yes. But I don’t know. I’m not a social scientist with that expertise. I don’t know what the data show about whether extremism is eradicable. I don’t know. But I do know that extremist groups represent a tiny minority of the people around. If we let them, they can take up a huge amount of the space that we have to think about each other, to think about our community, to enact policy and systematic changes for our community, and I don’t think we can or should spend as much time on that.

There are going to be folks who live in very extreme ways. I’m going to respect them. I want to treat them with dignity. But the majority of us see each other and see a sense of common ground. We may not agree on everything—and, by the way, I don’t want us to all agree on everything. I think this would be a really sad community if all of us agreed on everything, and I would be very concerned for us. We can have deep disagreements and deep respect and love for each other.

It’s hard. I’m not saying that this is easy work. It’s hard work. But I think it’s worth it. And I think what it’s showing us is that there is a lot of benefit that comes from pluralistic societies that make space for difference and for each other. We don’t have to understand absolutely every element of every identity out there. I think it’s impossible to do that. But we can certainly make space for people to live their full authentic selves and to live to their best capacity. When we do that, especially for those in our community who are the most marginalized, we elevate the whole community. The better job we do, I believe, of taking care of those who have been on the outskirts, the better job we do for everyone. And we need to focus on that more than focusing on the tiny minority of folks or groups who live in the extremist outskirts of different ideologies.

Some talk about colleges as places people aren’t allowed to express points of view that may have been standard twenty, thirty, or fifty years ago. What do you say to that?

It can be easy to rest in echo chambers of people who believe like you, speak like you, think like you. It’s harder to be a community when there are deeply held distinct beliefs and still deeply held respect and dignity for each other. I want Bowdoin to be—and I think we are—the latter. We want to be brave. We want to be critical. That is foundational to the scientific process, to the democratic process, and to the diversity process.

Our students, years from now, will be leading the most diverse workforce ever. It only helps to know about religious and cultural holidays, to know how to attract and retain a global workforce and a global clientele. I think we’re doing really good work preparing students to excel in today’s world and to lead in tomorrow’s world too.

What does a good day look like for you?

I love that question. A good day often has tons of meetings where I’m talking to colleagues about how we are supporting students. A good day also looks like getting ready for a program where students are going to get together and center a part of their identity with others who are part of their community and celebrate. Normally, there’s food. Normally, there’s really good music, a lot of laugher, and a lot of community-making.

I also think a good day involves us continuing to think about what are we missing? Who are we missing? What do we need to do to make this better? Because a good day also includes a lot of learning for each other and for ourselves.

What do you say to an older white man who says, “Between toxic masculinity and white privilege I feel like I’m supposed to apologize for my existence”?

I am a man, and I think a lot about this. If you look at the data, in terms of performance and overall wellness, men are struggling. We’re dying earlier. We’re more addicted to substances. We die by suicide more often, we access mental health resources at very low rates. Nationally, men take longer to graduate college and do so with lower GPAs, and fewer men than women are entering college. Men are struggling. Call it whatever you want to call it, but there is no doubt that the system of “traditional masculinity” men built for themselves over the last century is not working, and we’re seeing the effects on men in our country. This does not mean that we no longer have entire societal systems that advantage men and disadvantage women. Those are very much still there—the pay gap, the glass ceiling—but both things can be true at the same time. That is part of what we mean when we talk about “toxic masculinity” and why it is so important that we talk about healthier ways to embrace masculinities and work together for the health and wellness of all people. At the end of the day, I want to see us in a place where all people—regardless of gender—are thriving.

When we look back at who we were even ten years ago, hopefully we have changed. I have changed a lot. My language has changed. The things I appreciate have changed. The things I laugh about and the things I don’t have changed. The things I cry about, and the things I don’t have changed. Change is the only constant.

So what do I say to someone who feels like they’ve been alienated and left behind? I say we need you. We need everyone. But more than anything, we need older white men right now to say, “I want to live in a place where people can truly bring their full authentic selves, where people are healthier and have more access and there is less poverty and oppression.” There is plenty of work to be done for my dear friends, those men. We cannot do this without them.

Eduardo Pazos Palma is assistant dean of student affairs for inclusion and diversity and director of multicultural student life. Born and raised in Mexico, he graduated from Boston Baptist College and earned a master’s degree at Yale Divinity School. Prior to joining Bowdoin, he worked in higher education, in business and finance, and as pastor and chaplain for immigrant families in Texas.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.