Professors Discuss the History Behind Supreme Court's Roe v. Wade and Dobbs Decisions

By Mira Pickus ’24Associate Professor of History Meghan Roberts opened up a recent discussion on the history behind the Supreme Court's momentous decision to overturn Roe v. Wade with a surprising statement (for those not well versed in pre-modern customs, that is).

"Abortion actually was not illegal for much of European history," she said. “It's really a nineteenth-century development."

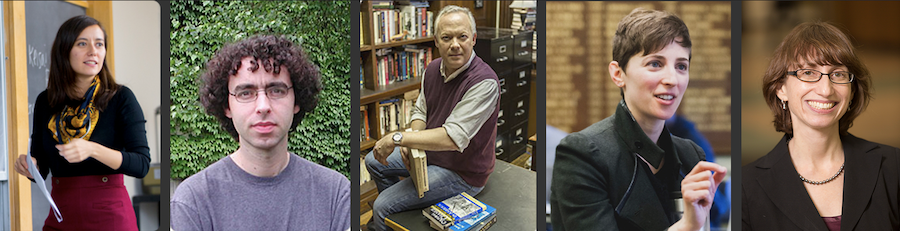

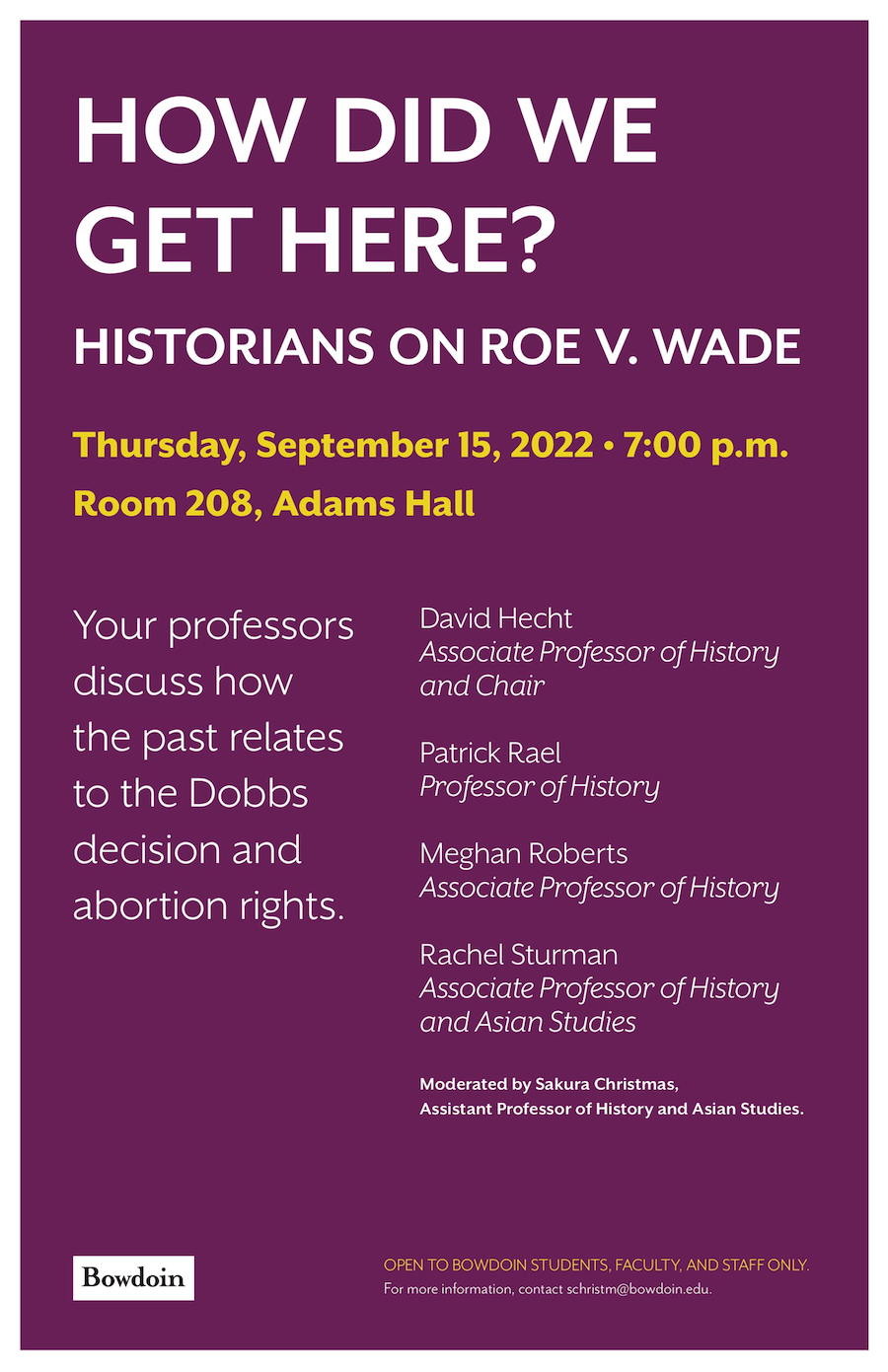

Roberts was part of a five-member panel of historians who had convened to discuss the historical backdrop of the ongoing conflict surrounding abortion rights.

Moderated by Sakura Christmas, a professor of history and Asian Studies, the panel consisted of Bowdoin professors David Hecht, Patrick Rael, Roberts, and Rachel Sturman. Their specialties include the history of science and medicine, women and gender, African Americans, and South Asia, among others.

“Abortion existed as a twilight practice,” Roberts continued. “Which is to say, it was widely understood to be a fact of life. People were doing this, [even though] people felt uneasy about it."

Together, the professors outlined a more nuanced narrative of abortion, offering a contrast to the one most often in the news, which presents abortion as a modern and intensely politicized conflict along the lines of pro-choice and pro-life. They broadened the conventional parameters of the debate to include ones that touched on past norms around medicine, law, women's rights, sex, death, religion, and community.

In early-modern Europe, while you wouldn't see a lot of people who were "pro-choice in the same way a person might be today," Roberts said, abortion was tolerated—in certain situations.

These included breakups in some cases. While premarital sex was common in the early modern period, it was also customary for the amorous couple to have publicly declared their intention to marry. Yet, if a man reneged on his promise, leaving his partner pregnant and single, her family—indeed, even her community and religious leaders—might help her terminate the pregnancy, Roberts explained.

A woman's community and family would also tolerate an abortion if she had been raped, or if the pregnancy threatened her health. Additionally, "abortion was tolerated when it was perceived as preventing a hardship that was already present in the woman's life...that is, if she was poor or dealing with an illness."

Roberts then noted a significant moment in 1588 when those attitudes were challenged by a pope who issued a declaration that all abortion was murder. Yet it took only three years for his decision to be overturned by the next pope. ""This was such an extreme position that there was immediate resistance," she said.

Hecht drew a parallel between early modern Europe and the United States during the century or so that abortion was illegal here, approximately 1870 to 1973. "That kind of uneasy acceptance was also true of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century United States," he said. "And the roughly hundred years when abortion was illegal didn't correspond to changing opinion," since a lot of historical evidence points to abortion continuing despite the laws prohibiting it.

"So the fact of it being illegal didn't change the social situation on the ground," he said.

The panel’s perspective on the recent court decision, Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, came with other contextual insights.

In response to a student’s question about Roe’s potential impacts on contraception, Rael engaged listeners in the specifics of the Fourteenth Amendment and privacy laws. He explained that according to Justice Samuel Alito's originalist construction of the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment, “rights stopped evolving” when the documents were ratified (1868 in the case of the Fourteenth Amendment).

Indeed, for some law practitioners like Alito, rights not “visibly laid out” in the Fourteenth Amendment cannot be constitutionally protected. Under this stagnant progression of rights, privacy and body autonomy are not subject to defense by the Supreme Court. Thus, gay marriage, contraception, and abortion—these more intimate, private matters—lack a tactile, permanent, law-bound tether.

After considering the topics of premarital sex, the Constitution, state versus federal law, and much more, the discussion arrived at the issue of science. The professors helped break open the subject of abortion by not only providing hidden historical narratives and facts, but by parsing the language with which we carry out this debate.

Students asked about the significance of "viability," the stage at which a fetus can live outside of the womb, or, in other words, is deemed a living human being.

For the Supreme Court, when it passed down its decision in Roe v. Wade it determined that states could not ban abortion before viability, which at the time was roughly considered to be twenty-eight weeks.

Hecht noted that despite the veneer of science that the decision rested on, the definition and understanding of viability is actually vague and variable. "The available technology in 1973 is not the same as it would be years later," he said. "Viability for someone with a lot of resources in a good hospital is not the same for someone with fewer resources."

So then, what is viability? “Is it some kind of average?" Hecht asked. "In attempting to put this question on some kind of medical ground in Roe, it had the illusion of creating a kind of standard, but it actually opened up a whole lot of questions," he said, as well as challenges to the law.

In the end, the panel’s ability to elongate the history of abortion, making it more than the topic of the moment, allowed students and other audience members to consider, reconsider, and contextualize their views on the issue and the Supreme Court’s recent major decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.