Following Maps to Study History and Become Stronger Students

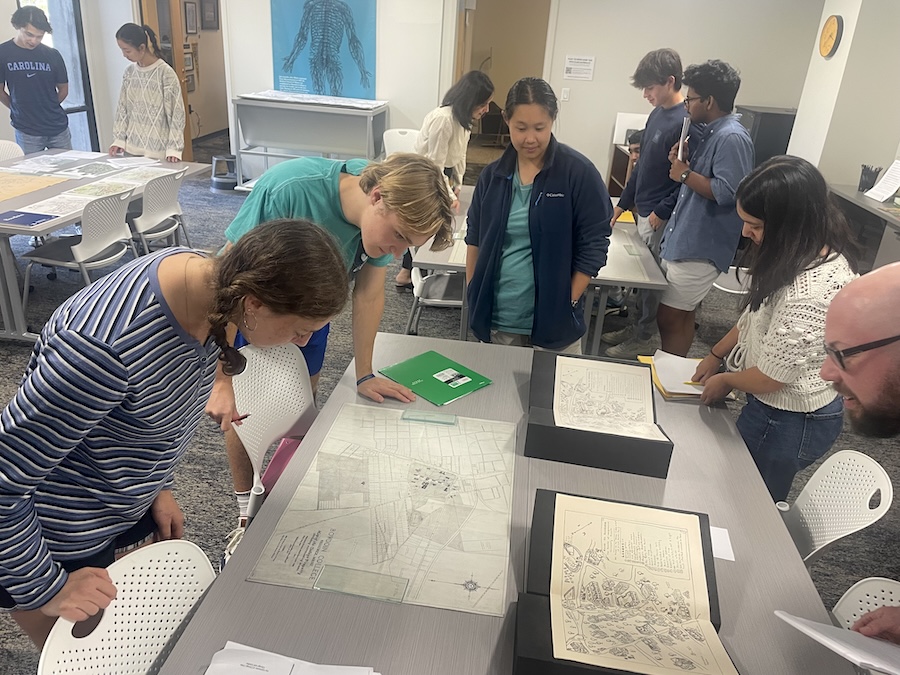

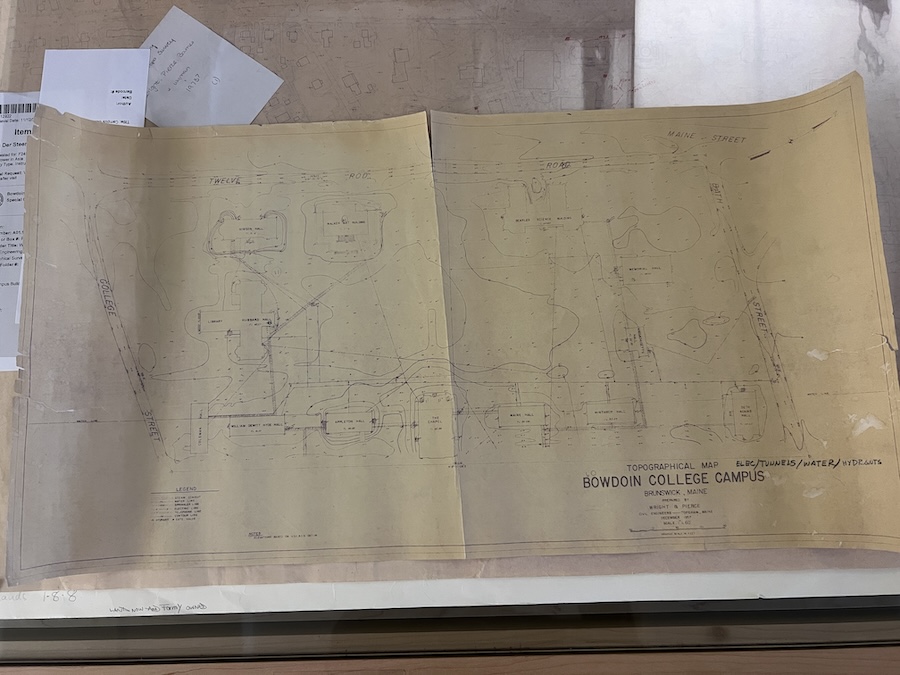

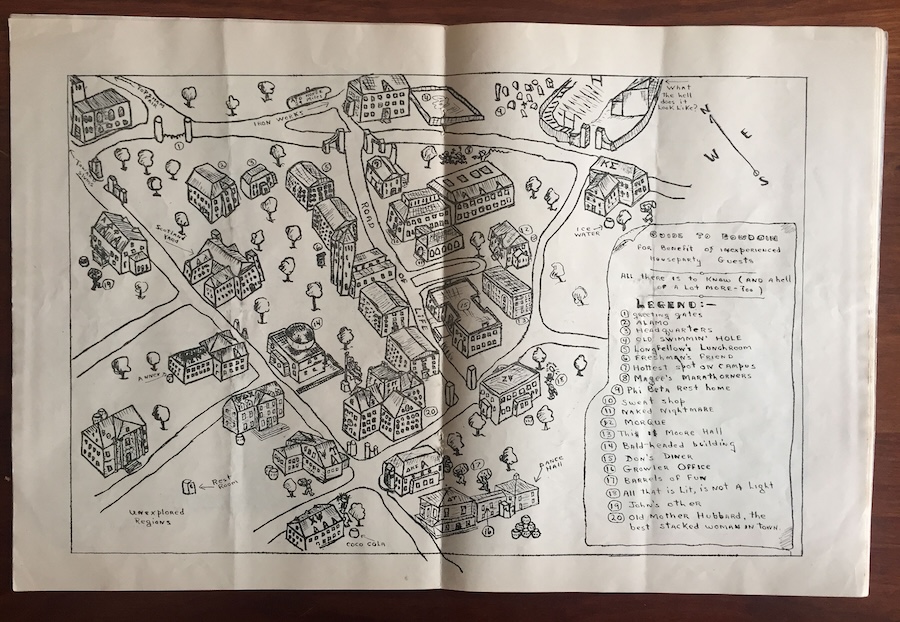

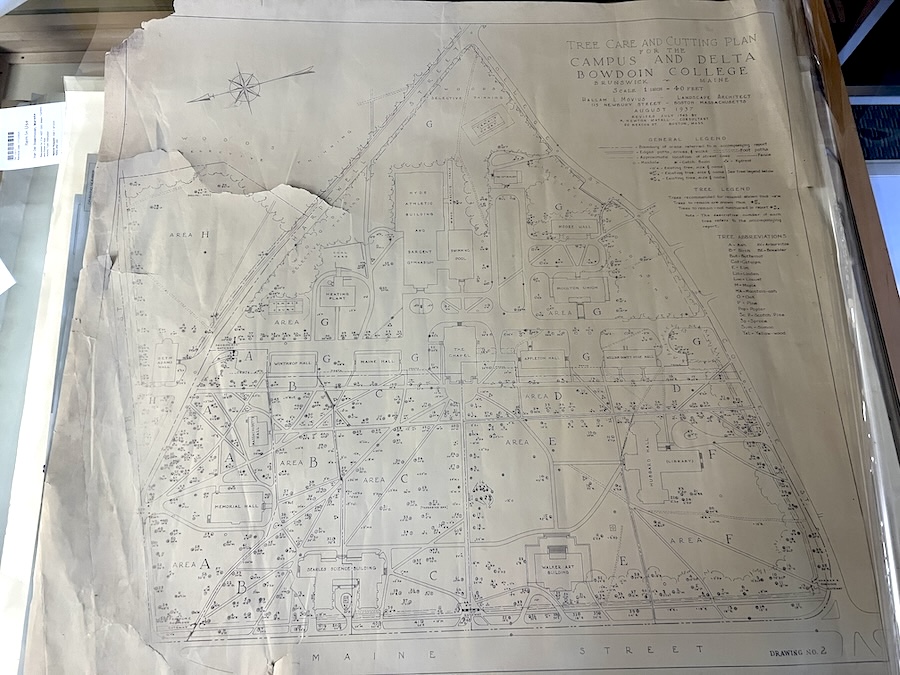

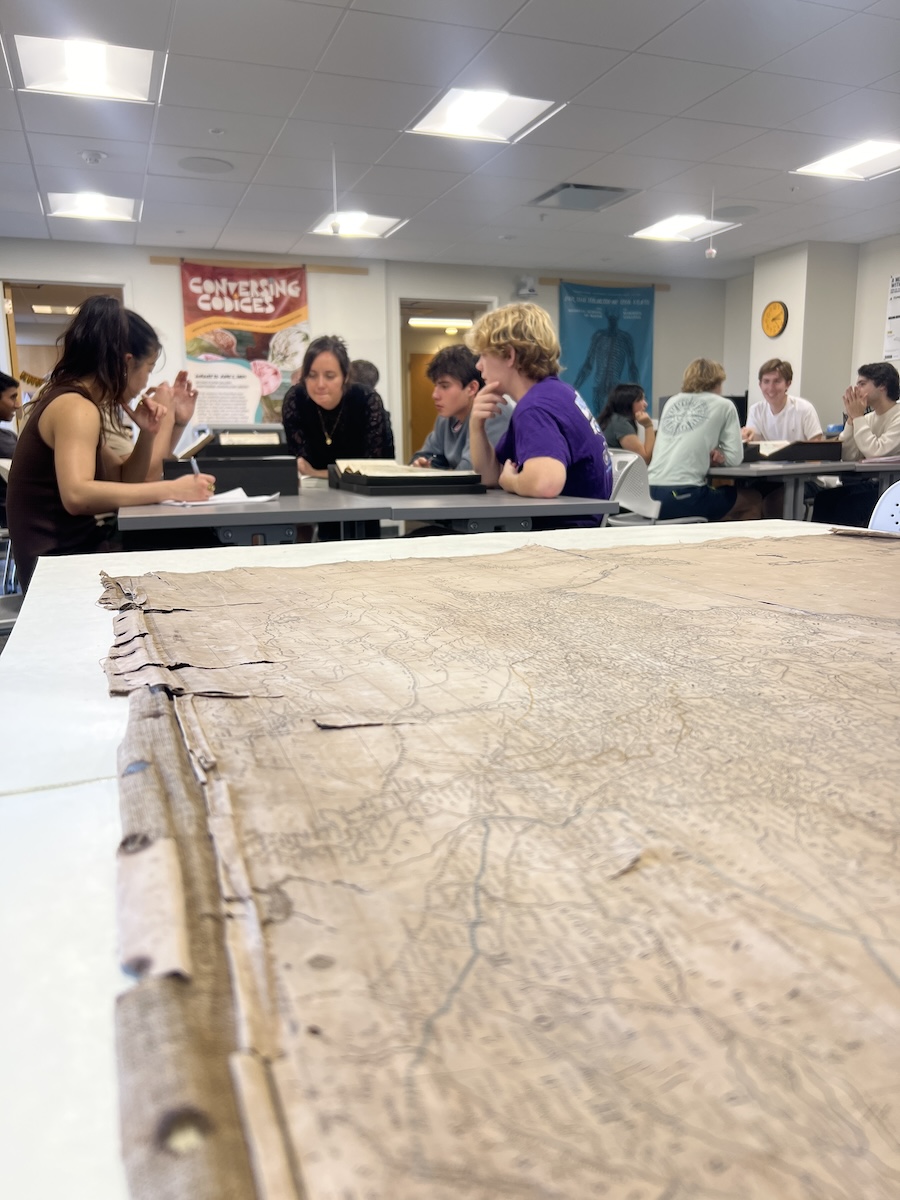

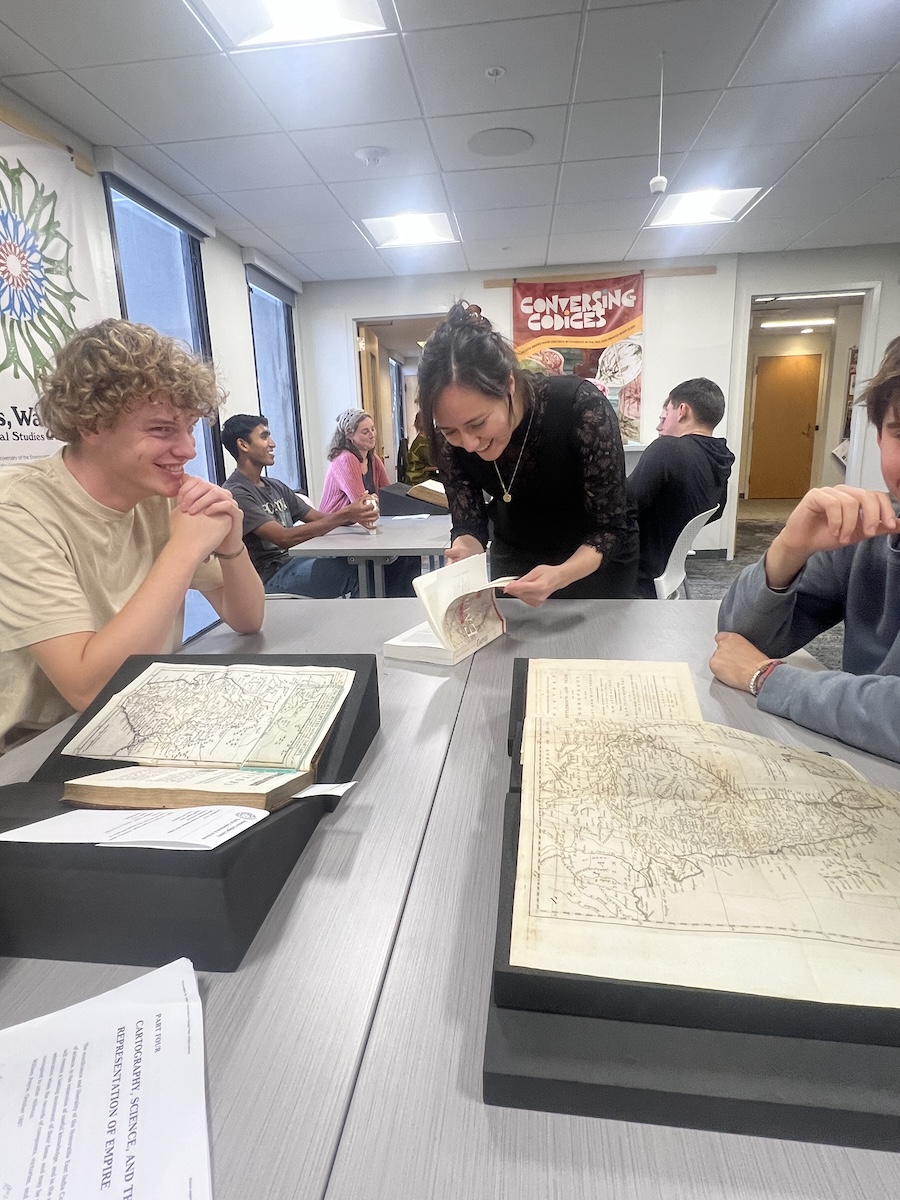

By Rebecca GoldfineOn the first of five visits to Special Collections & Archives this semester, first-year students in the seminar Maps, Territory, and Power in Asia leaned over large tables to peer at maps of the Bowdoin campus. Some of the yellowing sheets had tattered edges, or deep creases from fold lines. Many were drawn by hand in ink.

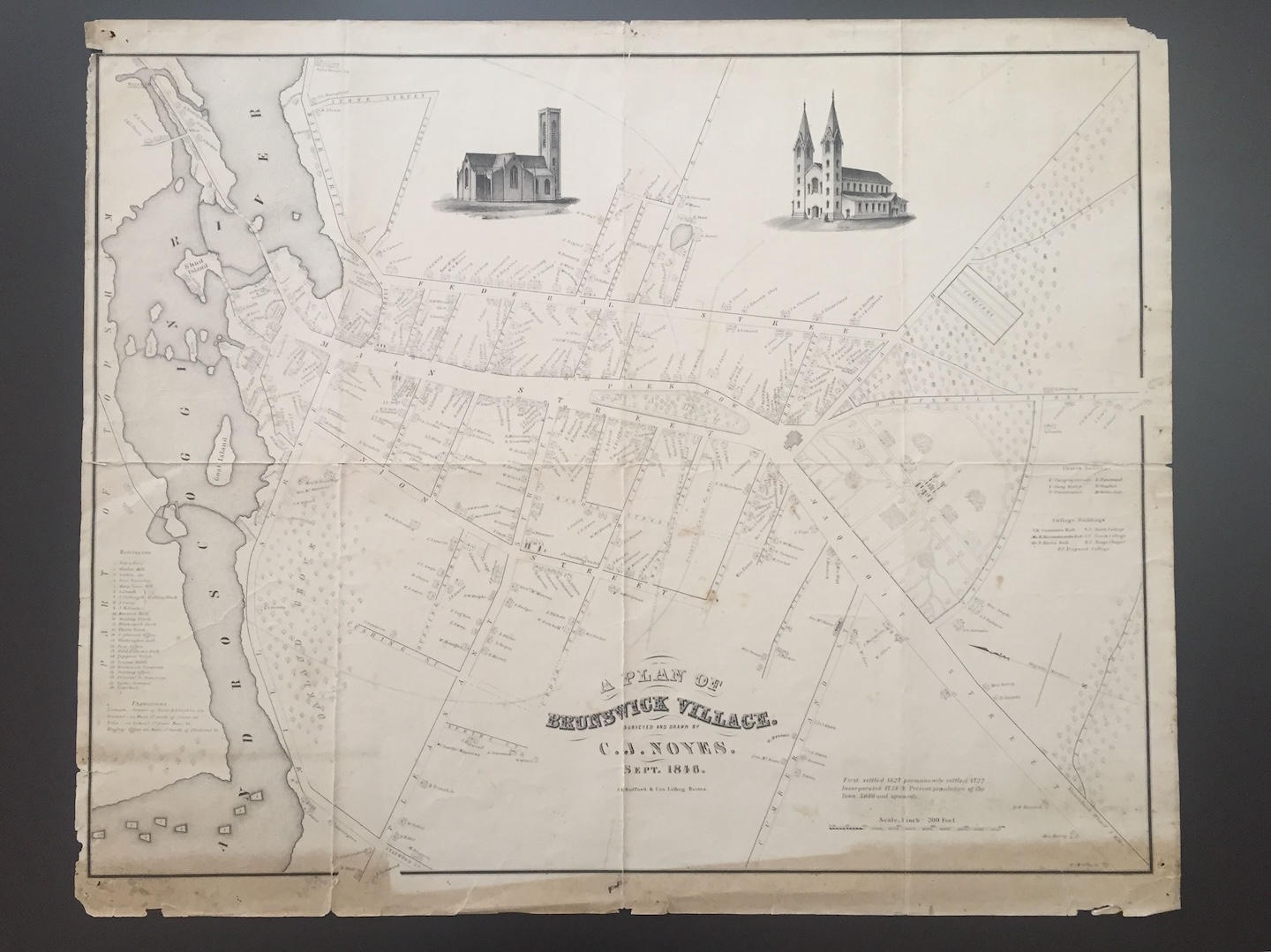

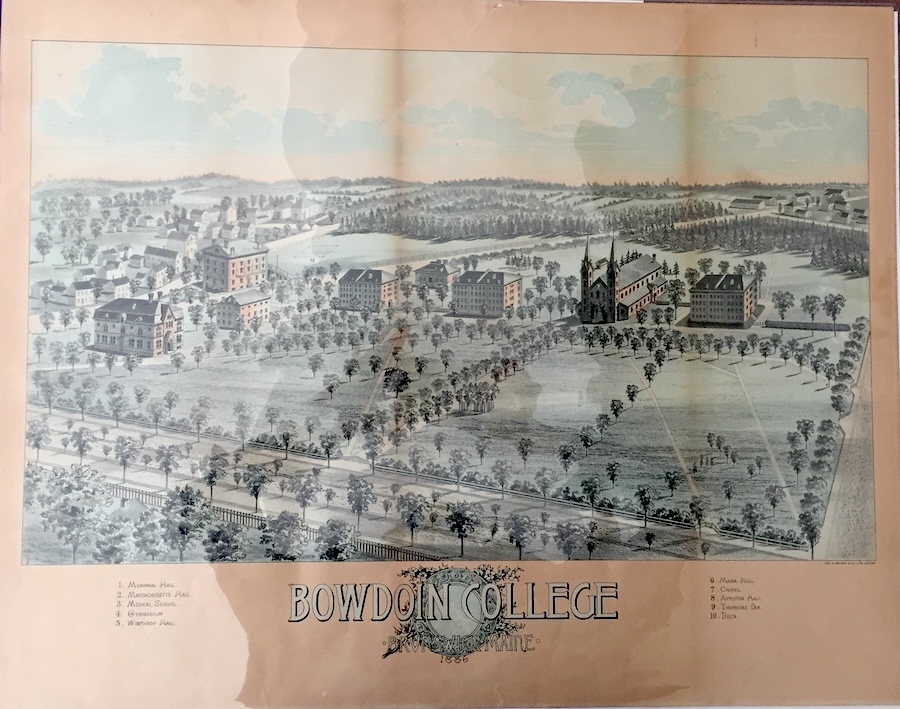

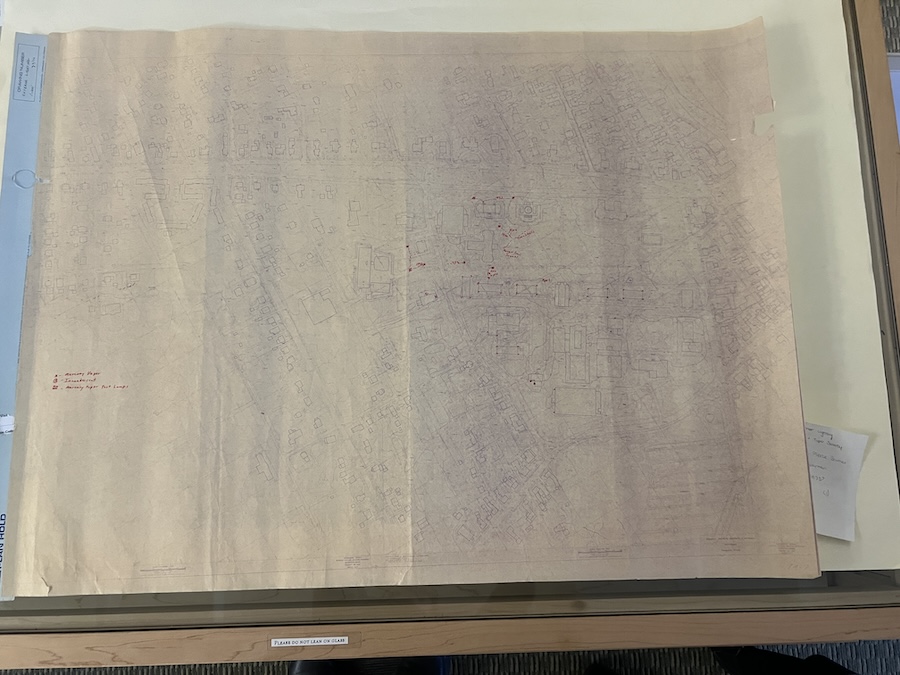

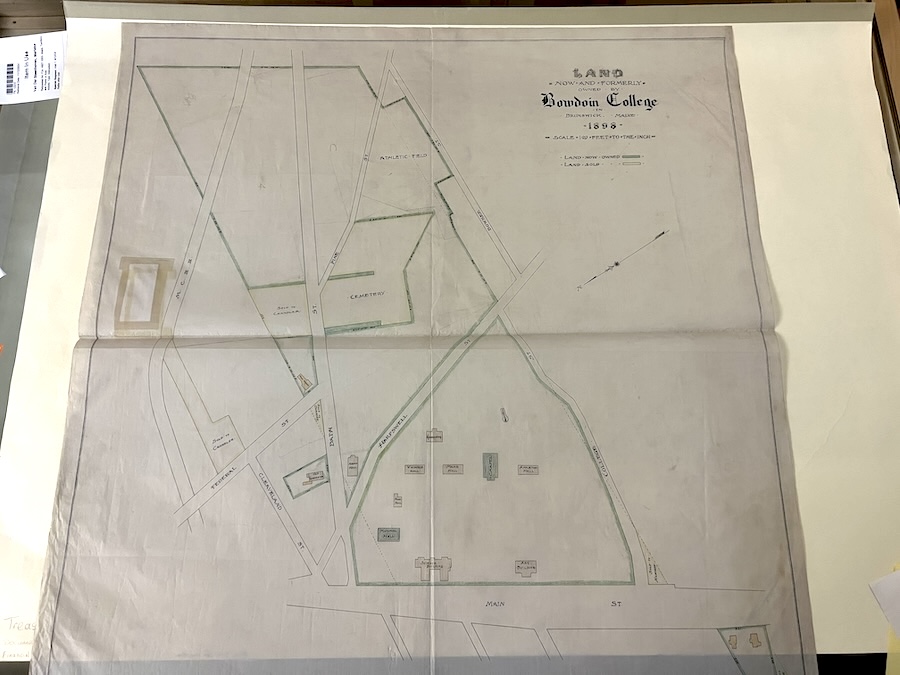

The oldest map they looked at was made in 1846—a detailed rendering of every residence and structure, including College buildings, in central Brunswick. Others were drafted in 1886, 1932, 1947, 1958, 1979—all the way to present day.

Each presented a different aspect of campus—e.g., underground steam tunnels, campus lighting, trees, or even the best party spots (thanks to the Growlers' 1932 and 1947 "Guide to Bowdoin for Benefit of Inexperienced Houseparty Guests.”

Although Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Sakura Christmas focuses her class on Asia, she asks students to examine Brunswick and Bowdoin cartography early in the semester to develop the practice of critically reading maps.

The Department of Special Collections & Archives at Bowdoin can easily facilitate this activity because it has hundreds of maps of Bowdoin, ranging from the 1820s to the latest iteration of the admissions map.

A Lab for the Humanities

One aspect of Marieke Van Der Steenhoven’s position as Special Collections Education and Engagement Librarian is to collaborate with faculty who want their students to engage with historical materials from the Special Collections & Archives. In this capacity, she has partnered with Christmas to teach her map-based sessions.

This semester, Special Collections & Archives is supporting twenty-five classes. In response to increasing demand, Jamey Tanzer’s role as research services librarian has expanded to include supporting Marieke Van Der Steenhoven and SC&A’s instruction program.

- ARTH 1120/ASNS 1865: Introduction to Art History: The Body in East Asian Art

- ARTH 2510: Industry and Imperialism

- ARTH 2710/ASNS 2020: Cosmographies and Ecologies in Chinese Art

- ARTH 3840: Bad Art

- BIOL 3320: Natural History of Maine

- CLAS 3310/URBS 3410: Imagining Rome

- ENGL 1005: Victorian Ghosts and Monsters

- ENGL 2852: Reading Uncle Tom's Cabin

- ENGL3002: James Joyce Revolution

- FRS/AFRS 2409/LACL 2209: Spoken Word and Written Text

- HISP/GSWS/LACL 3231: Sor Juana and María de Zayas: Early Modern Feminisms

- HISP/LACL/THTR 2409: Introduction to Hispanic Literature, Poetry, and Theater

- HIST 1003: Maps, Territory, and Power in Asia

- HIST 2048: The Worlds of the Middle Ages

- HIST 2543: European Bodies

- HIST/AFRS 1461: African Civilizations to 1850: Myth, Art, and History

- HIST/LACL 1047: Witches, Heretics, and other Microhistories from the Inquisition

- HIST2342: Making of Modern India and Pakistan

- LACL/GSWS 1045: Social Justice Warriors

- MUS 1101 Sound Self and Society: Music and Everyday Life

- MUS 2305: Beethoven and the Invention of Western Music

- VART 1601: Sculpture I

- VART 1201: Printmaking I

- VART 1301: Painting I

VART 2203: The Printed Book

A classroom in the library, next door to Van Der Steenhoven's office, is dedicated to this purpose. “We use this space as a laboratory, to work through and work on concepts that students are introduced to in class,” Van Der Steenhoven said.

Christmas has taught Maps, Territory, and Power in Asia several times since 2016, though this fall is the first year she has offered it as a first-year writing seminar. The class examines the histories of countries in Asia—including China, Japan, Vietnam, the Koreas, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh—through maps. It challenges students to think about how such records have legitimized colonial, national, and imperial claims from the seventeenth century to the present, according to its catalogue description.

Christmas decided to convert her upper-level history course this year into a first-year seminar in part because maps are so accessible. “They make for great objects to think about critically, and chances are the students hadn’t thought about them that way before,” she said. Plus, “there is a subset of students who are obsessed with maps!”

For the first lab, about Bowdoin, Van Der Steenhoven sifted through Bowdoin's huge map collection, selecting a handful that tell an interesting story about the College at a particular time.

One map she finds particularly compelling is a topographical map from 1973 that locates mercury vapor lamp posts, either ones already in existence along campus walkways or ones the College wanted to add. Van Der Steenhoven pointed out that the map was made just two years after the first class of female students had matriculated at Bowdoin, drawing an inference about heightened security concerns not explicitly spelled out on the map.

Scrolling through Bowdoin's History: Campus Maps from 2015 to 1898.

Showing maps of Bowdoin from the past two centuries to students who either know the campus well, or who will get to know it well, makes for an engaging introduction to map reading, said Van Der Steenhoven. “Studying maps of Bowdoin is like reading a cookbook—you can have an immediate visceral reaction because you're familiar with it, and the familiarity with the place allows you to navigate the map much more easily,” she said. “You can quickly orient yourself, so you can do this quick calculation, ‘What is the same and what is different?'”

They then move quickly to the crux of the exercise. “By putting together all of these diverse representations of Bowdoin from the 1840s to 2000-something—with some maps about trees versus utilities, versus admissions, versus partying—it allows students to see how things change over time and also the strong perspectives that have shaped each map.”

To prepare for their first lab on the topic, students read Mark Monmonier's How to Lie with Maps. They are then asked to consider why and for what audience a map was created and the point of view of the mapmaker.

“One of the points of the class is to disabuse students of objectivity, since all maps have some sort of argument they’re seeking to make, even while some are using scientific objectivity to make those arguments,” Christmas said.

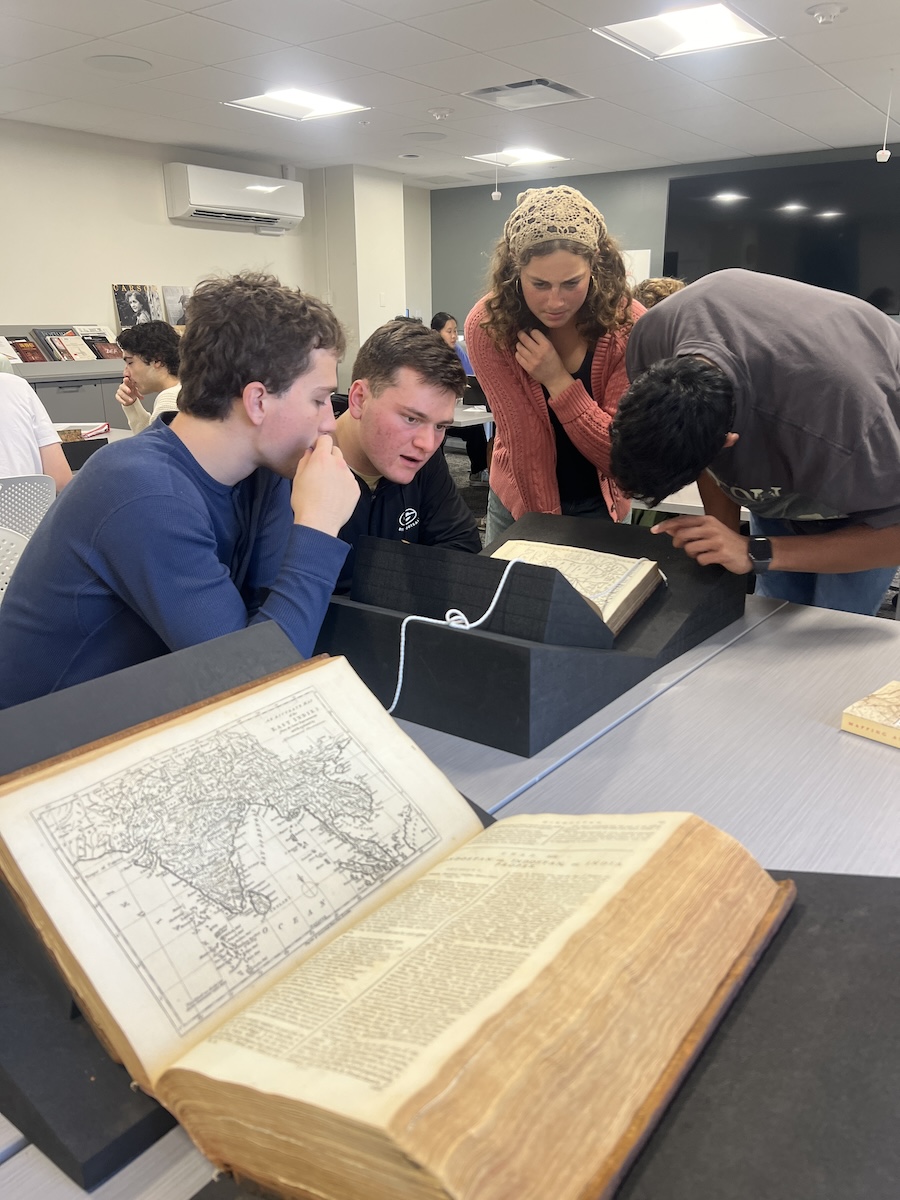

Collier Zug ’28, a first-year student in the class, said he signed up for the seminar because he loves history and wanted to learn more about a part of the world he didn't know much about. He’s since grown to also appreciate maps. “I love learning about the different historiographical techniques of making maps, and about the ways in which maps have been used to further empire building and nationalist ideas—how maps are used to further the ends of rulers who create them,” he said.

Another student in the class, Maya Salter ’28, said she was drawn to the seminar because she’s one of those people who loves maps. “As someone who hikes, I find topographic maps interesting, and I am interested in art and have a visual interest in maps.” Yet, while she said she likes looking at “cool maps,” even more valuable to her has been learning how to clearly express her ideas in writing, as well as developing the patience and endurance to work through challenging texts.

First-year writing seminars are meant to prepare new students at Bowdoin for college-level writing, reading, and studying. Additionally, these seminars are an opportunity to spark a student’s interest in a major and for them to acquire the skills for upper-level classes in that discipline, Christmas said. “What better way to do that for history then to get students into Special Collections multiple times, so they can work with the materiality of their sources?” she said.

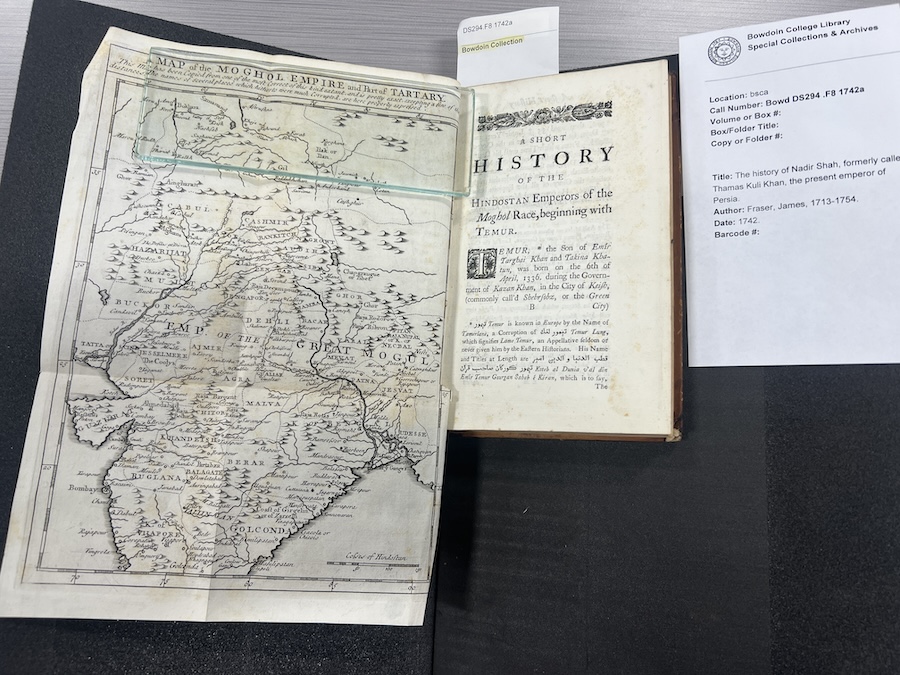

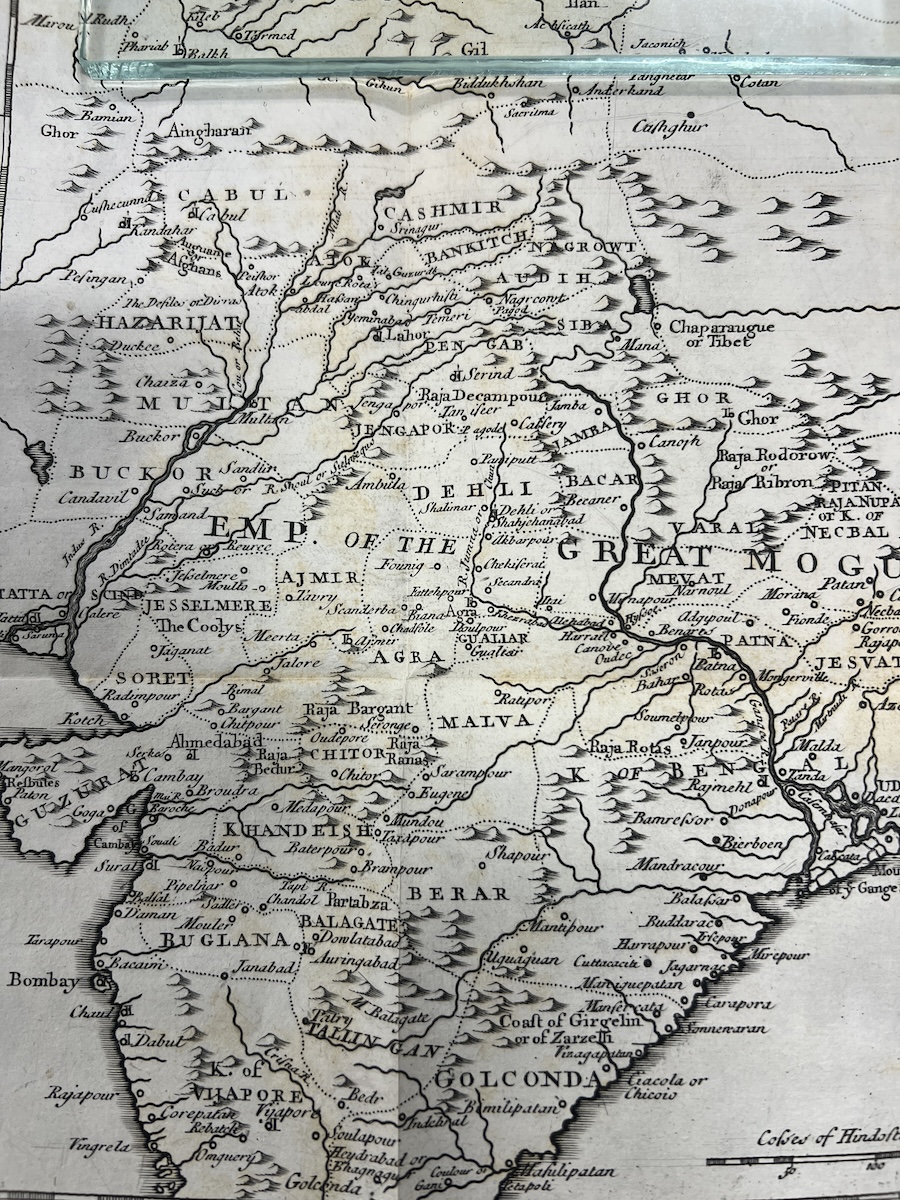

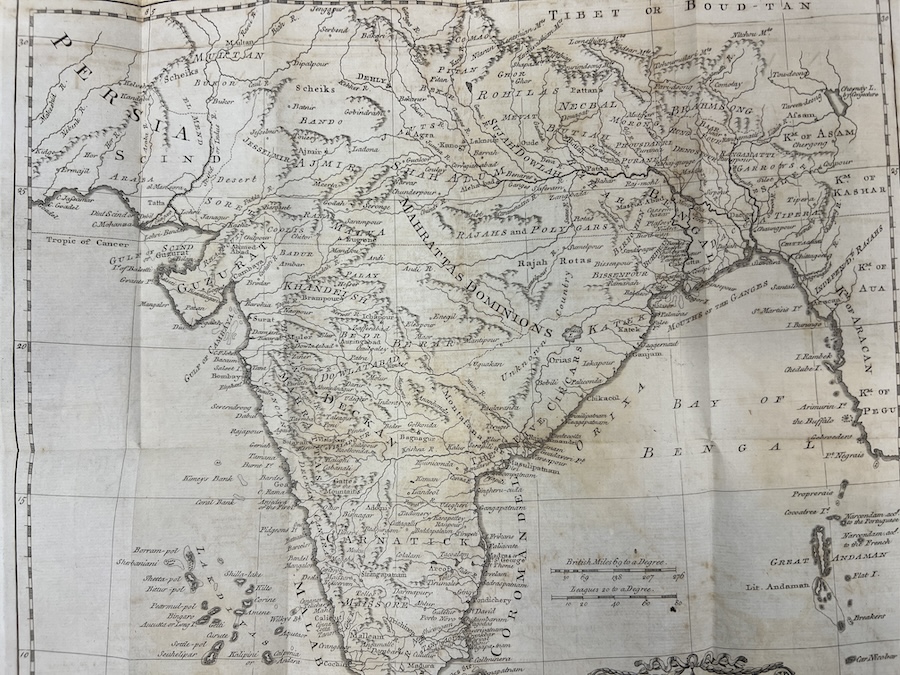

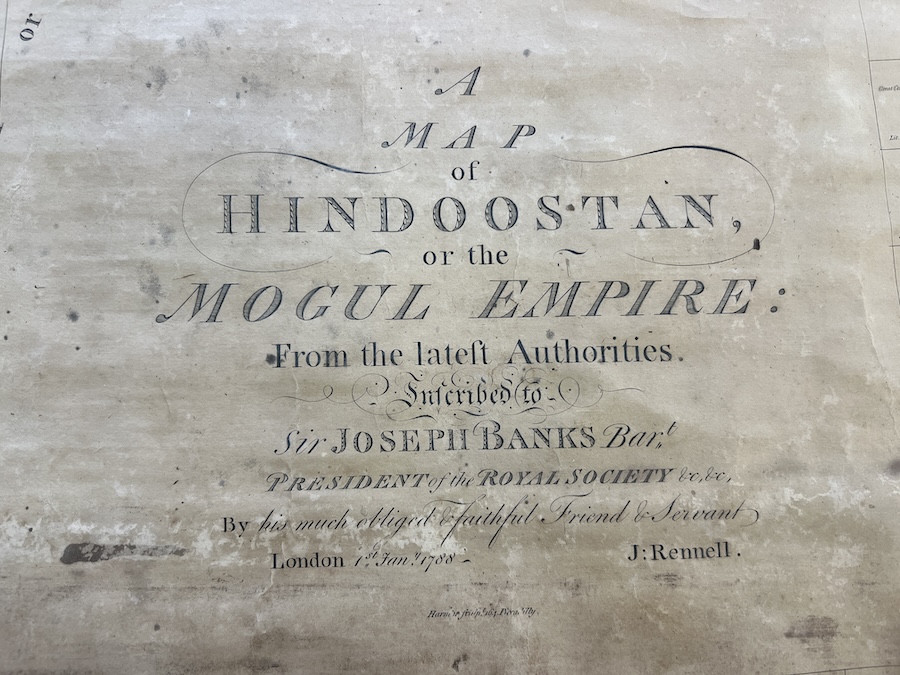

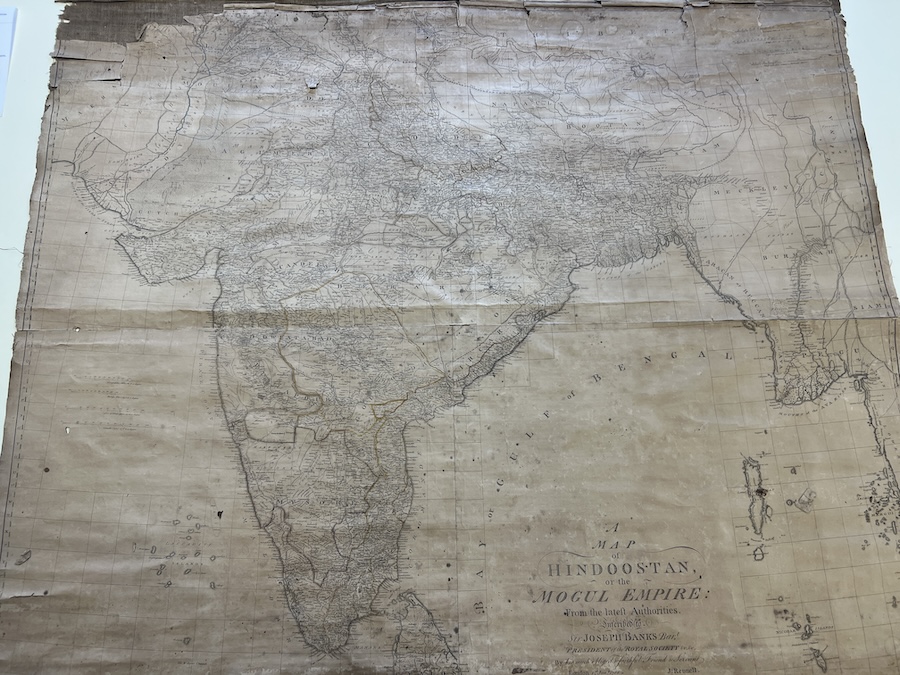

Maps of India, from Special Collections. Click here for their sources.

More Maps, Territory, and Power in Special Collections

For each of the visits Christmas's class makes to Special Collections, Van Der Steenhoven delivers a dozen or so maps from the archives.

The many maps used for the class’s labs derive from diverse sources that have found their way to Bowdoin’s library along different pathways. Some are from the library of Donald MacMillan, the famous Arctic explorer who graduated from Bowdoin in 1898 (the same year the map shown above, “Land Now and Formerly Owned by Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine,” was printed). Others come from the collection of James Bowdoin III, who bequeathed his library to the College in 1811. Many of the maps are bound in books, including travel narratives published in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Others, particularly of campus buildings and utilities, are part of the official record of the College.

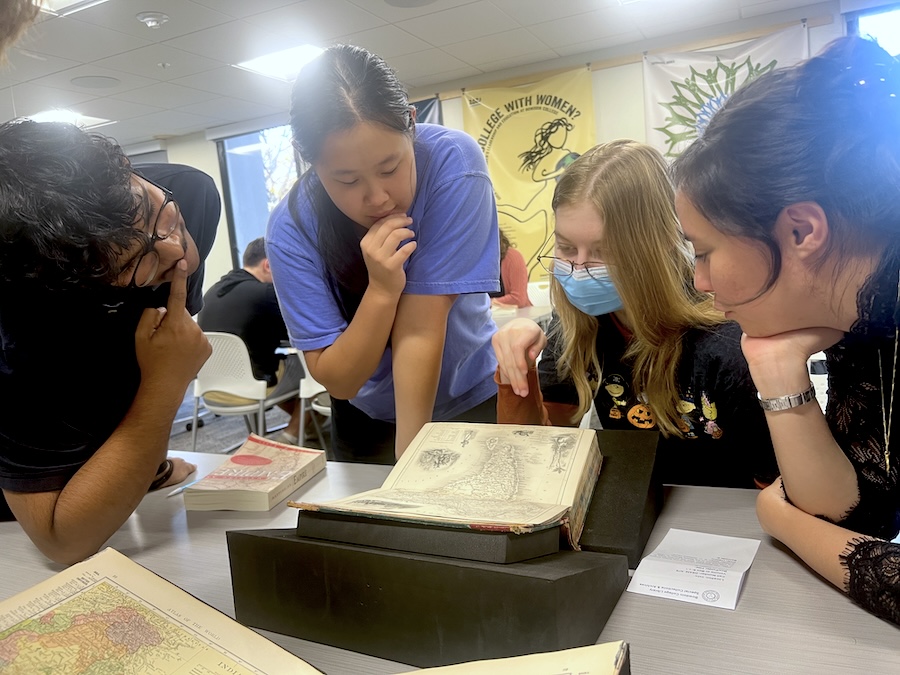

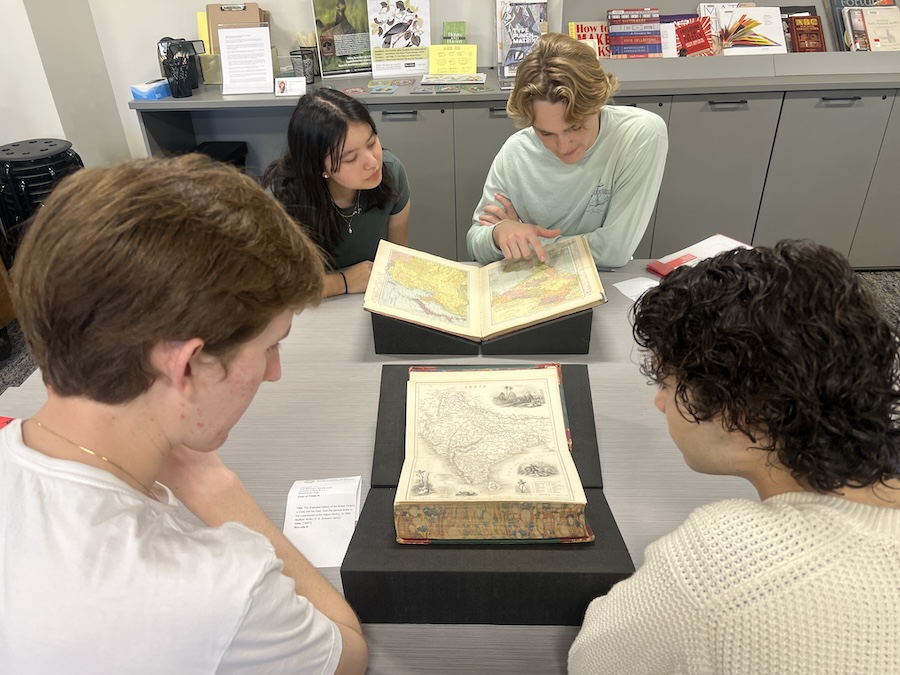

For the class’s third lab, in late October, Van Der Steenhoven presented nine maps of India—or, rather, of the land that eventually became India. The oldest was from 1625, showing “Indostan,” in Samuel Purchas’s Purchas his Pilgrimes, contayning a history of the world, in sea voyages, & lande-trauells by Englishmen and others. “The map is framed around the Mughal empire before it began its expansion southward,” explained Christmas. “It’s a conception of what India might be.”

![Nihonbashi Yori 日本橋 本橋ヨリ [Tokugawa woodblock print map]. Tōto 東都 (Edo/Tokyo). Bunkyu 2 [1862]. Color woodblock print map of Edo (Tokyo), oriented with North to the right. Originally published in Kaiei 2 [1849], this updated map was republished in 1862. Publisher is given as Yorozuya Seibe 萬屋在助枚 with an address in Asakusa.](../images/map-of-edo.png)

Special Collections this fall bought two new maps to support Christmas's history courses: this 1862 woodblock print map of Edo above and an 1895 map of Tokyo.

Christmas said these maps help to broaden the historical perspectives offered by the library's map holdings, since many of Bowdoin's older maps were collected by eighteenth-century American and European intellectuals influenced by Western notions about Asia at that time.

As the students studied the other maps—from 1790 to 1904, all published in British or American books—they discussed the emergence of India from before the Mughal empire, through British colonization, to nationalism and independence. Though none of the maps they looked at were made by a local cartographer, they “can teach students about Orientalism and the ways in which Europe portrayed much of Asia during this period of time,” Christmas said.

However, one of the elements students searched for on the maps was a sign of indigenous knowledge. A student pointed to a map legend showing kos units, an ancient form of measurement in the Indian subcontinent that marked the farthest distance from which you could hear a person's call. Cartographers began to standardize kos measurements during the British period.

The students moved around the room, discussing the history they saw written and drawn on the map, in its legends, land boundaries, names of regions and landforms, and iconography or in the images of symbols, people, animals, and scenes.

At the end of the lab, the students could visualize the trajectory of modern-day India and the role that empires, global trade, and mapmakers played in its development. Maps are singular in how they allow us to peer back into time from a unique vantage that helps us better understand both where we have been in the past and where we are today.

“They allow us to understand our position in accessing historical sources—to ask what do we know now? Maps force curiosity and inquiry,” Van Der Steenhoven said.

![“Indostan” in Purchas, Samuel. Haklvytvs posthumus, or, Pvrchas his Pilgrimes : contayning a history of the world, in sea voyages, & lande-trauells / by Englishmen and others, wherein Gods wonders in nature & prouidence, the actes, arts, varieties & vanities of men, w[i]th a world of the worlds rarities are by a world of eyewitnesse-authors related to the world, some left written by Mr. Hakluyt at his death, more since added, his also perused, & perfected, all examined, abreuiated, illustrated w[i]th notes, enlarged w[i]th discourses, adorned w[i]th pictures, and expressed in mapps, in fower parts, each containing fiue books. [London]: Imprinted at London for Henry Fetherston at y[e]e signe of the rose in Pauls Churchyard, 1625. Call #: STC 20509 folio v.1](../images/map-class_5919a.jpg)

![“India” in Nolan, E. H. The illustrated history of the British Empire in India and the East, from the earliest times to the suppression of the Sepoy Mutiny, in 1859. London, New York, J.S. Virtue [1860?]. Call #: DS436 .N78 v.1](../images/map-class_5920.jpg)