Bowdoin’s McCarroll Honored for Anti-Racist Hiring Initiative

By Tom PorterThe Baldwin Center for Learning and Teaching employs about thirty-five student writing assistants. Their job involves working directly with students in helping them craft their written work. They also work with faculty in helping entire classes as they revise their papers.

Since the introduction of an identity-blind selection process, Bowdoin's writing assistants have diversified from roughly 5 to 10 percent students of color to 60 percent students of color.

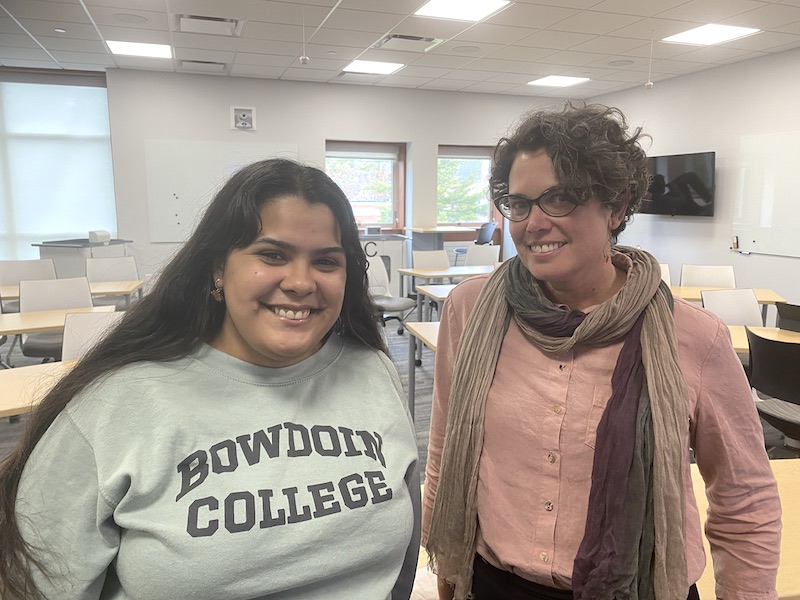

“Writing assistants take a full credit course in the spring to prepare them for the work, then they start in the fall and typically continue in that role for the rest of their time at Bowdoin,” said Meredith McCarroll. She’s director of writing and rhetoric at the College, where she also runs the writing program.

A writing assistantship is a paid position, she explained, and there are normally fifty to sixty applications for ten to twelve places. Most of the students who apply tend to come from a certain background, said McCarroll. “They’re usually white, prep school graduates who already have considerable writing experience and know what a writing center is.”

McCarroll was concerned that the writing center felt like a white space—staffed by mostly white students and most comfortable to white students. She worried that there was bias at play in the hiring process, which was guided chiefly by faculty nomination followed by an interview. “This method yielded mostly white applicants, and even when nonwhite students applied, they were rarely selected.”

She decided to try to change the hiring process, hopeful that it would change the writing assistant demographic so as to reflect the more diverse nature of the student body at Bowdoin and in turn make nonwhite students feel more comfortable working with writing assistants. The first step was to encourage more students from nontraditional backgrounds to apply while also appealing to faculty members to recommend more diverse students for the role. Even after this had been done, however, the successful candidates still tended to be overwhelmingly white, said McCarroll. “So, the next thing I did was to remove the requirement for an in-person interview in the initial stages, instead relying on anonymous online applications involving a series of questions about writing process. Consequently, when I and the other writing assistants—who are also part of the selection process—read the applications, we have no idea who the student is or where they come from.”

“We believe the anti-racist framework employed by Bowdoin’s Writing Program represents many of the values of small liberal arts institutions,” wrote the prize committee members in a letter to McCarroll.

Applicants are then rated and discussed in more depth before their identities are revealed, she explained. “This new approach both drew more diverse applicants and yielded more diverse finalists.” McCarroll said any sort of diversity is considered to be an asset. “It could be racial or linguistic diversity, sexual orientation, gender identity, what major they’re taking, and much more. For example, if we’re short of athletes, we’ll try to recruit some; if we end up with all African American students from urban areas, then we might look for more white kids from rural Maine. We want to reflect the wide range of students we have at Bowdoin.”

In the two years since McCarroll started incorporating these methods, she said, the results have been encouraging. By using an identity-blind selection process, the writing assistants have diversified from roughly 5 to 10 percent students of color to 60 percent students of color. “The writing assistants now represent a more diverse student body, which in turn creates a more inclusive and welcoming space for all students. We don’t track the race of people who use the writing center, so I don’t have data on that, but we have introduced an optional survey, which could provide some guidance in the future.”

McCarroll’s efforts were recently recognized by her colleagues at an organization called the Small Liberal Arts Colleges-Writing Program Administrators (SLAC-WPA), which awarded her the 2021 Martinson Award for Innovation. “We believe the anti-racist framework employed by Bowdoin’s Writing Program represents many of the values of small liberal arts institutions,” wrote the prize committee members in a letter to McCarroll. “It takes a novel approach to combating implicit bias and to diversifying writing center staffing by doing identity-blind hiring (no interview).” McCarroll’s award will be formally recognized at an event in January 2022.

“It’s exciting to be acknowledged for doing innovative work in a field where it can feel really stagnating,” said McCarroll. This award, she stressed, shows that anti-racism initiatives can happen in places where you wouldn’t imagine them. “The work that’s being done at Bowdoin to remove implicit bias from our hiring practices demonstrates that there is space for anti-racist work across the board.”