Clear Facts

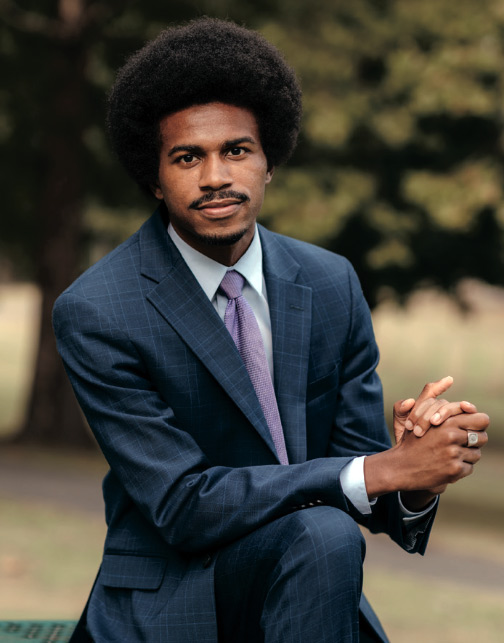

By Bowdoin MagazineBowdoin Trustee Shelley Hearne ’83 is the inaugural Deans Sommer and Klag Professor of the Practice for Public Health Advocacy and director of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg Center for Public Health Advocacy.

How do you square the body positivity movement with public health and health issues related to obesity?

How you feel about your body is just as important as your physical health. Shaming doesn’t have a place in good health—hallelujah for the body positivity movement. But just as important is tackling the social and physical conditions that have caused an obesity epidemic that accounts for such a significant increase in cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. Because of this, for the first time in our country’s history, we are going to be living shorter lives. Making sure everyone has access to nutritious, affordable food; ensuring safe, physical environments that let kids walk to school; providing parks for them to play in—these are just some of the measures that will help society combat obesity.

You work in the area of health equity and connecting the health of a community as a whole to its members. What does it take to achieve success in those areas? What are some of the obstacles?

In every city, every state, you can drive a few miles between neighborhoods where life expectancy can differ by as much as twenty years. It’s not race; it’s not genetics; it’s about structural racism and social conditions that cause different living conditions. Sidewalks in one, potholes and higher pedestrian deaths in the other. Access to quality education, financial security, transportation, housing—these factors all have enormous an impact on overall health and wellbeing. And policy is the key ingredient to assuring everyone has an equitable opportunity. But generating positive political action and change can also be the greatest challenge.

We read recently that an epidemiologist said, “Well, I never have to explain what an epidemiologist is any more.” Is that the case with public health?

There is a better understanding now about public health, but not a complete one. Public health is synonymous with disease prevention—for everyone. The focus right now is on the COVID-19 pandemic, but we can’t forget what’s an even greater problem: We are the wealthiest nation in the world, yet the sickest compared to all our peer nations. We have extreme health disparities along with epidemics of addictions, obesity, and chronic disease. We must modernize our public health system in order to properly address today’s threats.

Our society seems to see health as a private matter, one where everyone has an inalienable right to take care of themselves or not and that doing so, whether choosing to smoke or to not where a mask, is basically a contract between the individual and his or her body; nothing to do with society. Would you say that’s fair and particularly American? Does it seem to be changing at all with this pandemic?

Neither. I disagree with the framing of the question. Americans generally rally against dangerous, involuntary risks once the facts are clear. Today, it’s still your choice to drink, but drunk-driving is unacceptable. It’s your choice to smoke, but not to generate second-hand smoke that puts kids and others at risk. We will get there with masks too. Research now demonstrates that masks unequivocally save lives. The politicization of the pandemic has been costly, but with the election over, I believe the vast majority will do the right thing for everyone’s sake.

You’re the founder of Trust for America’s Health. Does that seem like an oxymoronic string of words right now? What can we do to change that? You talk about evidence-based problem solving and policies, but how do we get the public to trust that evidence so that we can use it to make policy?

Who do Americans trust most? Their doctor. Their healthcare workers. Ironically, Trust for America’s Health’s seminal work was scoring states for their readiness for major health emergencies. We assessed if they had adequate disease tracking and laboratories and epidemiologists, and whether they had a pandemic preparedness plan. That was in 2004. Would you believe it’s the same recommendations now for modernizing our public health system so that we can be a healthier, more resilient nation? It’s more than trust; its’ time to take action.

Where did you think your career would take you when you left Bowdoin with a degree in chemistry and environmental studies? How did you end up in public health?

My advisor, Dr. Sam Butcher, the chair of the chemistry department, recommended that I should go to public health school. I still remember shaking my head, wondering what that had to do with saving the planet. I graduated and went to NRDC [Natural Resources Defense Council]—the national environmental advocacy group—to fight against pesticides in food and antibiotics fed to farm animals. He was right—that is public health.

I think you played on the high school basketball team that won the New Jersey state championship in 1979—and I know you played basketball and lacrosse at Bowdoin as well. Are you a still a sports fan? If so, any favorites?

Ask Clayton Rose if I’m a sports fan. His shoulder may still be sore from my overexuberant cheering when the Bowdoin women’s basketball team played in the national championships. Go U Bears!

We read about the downside of youth sports a fair amount—concussions, hyper-scheduled kids, overbearing parents, abusive coaches. What’s your take on youth sports in our country today, both as a former athlete and as a public health leader?

I passionately believe that sports—or any positive, character-building, non-academic enterprise—are vital to good health and success in life. How about we create safe spaces for kids to play and better manage the adults!

This story first appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.