Hope the Hard Way

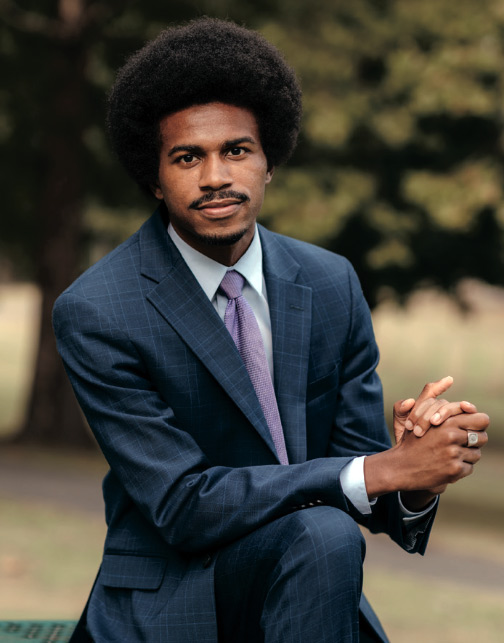

By Bowdoin MagazineDeRay Mckesson ’07 rose to national prominence in the Black Lives Matter movement beginning with the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after Michael Brown was killed by police. The former math teacher and school administrator is the author of last year’s On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope, and he continues his activism with his podcast, “Pod Save the People,” with Campaign Zero, an organization focused on policy solutions to end police brutality in America, and speaking engagements across the country.

We’ve seen nationwide protests since George Floyd’s murder in March, and you began your activism in 2014 in Ferguson after Michael Brown was killed by police. Do you feel like anything has changed? Has there been any progress in the past six years?

I think the conversation about racial injustice is at a fundamentally different place than it was before. In 2014, we were trying to help people understand that there was a systemic problem. I think in 2020, people get it. They’re like, “There is a problem.” The flipside is that, when we look at the numbers, police have actually killed more people today than they did last year. There wasn’t a dip during the COVID-19 quarantine lockdown. And with the [recent] protests, there’s actually no decrease at all, either. There’s a difference between awareness and a change in outcomes. There are many people who believe that the biggest work is to talk about the problem, that the biggest work is to expose the problem. That is the beginning of the work. The biggest work is to undo the problem.

Imagine if you had a job where it was impossible to get fired. The outcomes would probably be pretty wild. And that, actually, is what policing is—it’s very hard [to be fired]. Only 1 percent of officers are ever convicted of a crime. You can kill, and there will almost always be no consequence. When we look at convictions of police officers from 2010 to today, the year with the highest number of officers charged is 2015. That’s eighteen officers. Remember, the police kill 1,100* people a year on average, right? [*In 2019, according to mappingpoliceviolence.org.] Highest number charged is eighteen. The highest number convicted is also in 2015: eight. The odds are in your favor if you’re an officer. The odds that you can kill somebody, and the worst-case scenario, right now, is that you’ll have bad press.

Your book, On the Other Side of Freedom, is subtitled The Case for Hope, and we’re in the middle of two pandemics—the health crisis and ongoing historic systemic racism in our country. And it doesn’t look like either of them are getting better. Amid all of this, where do you see hope?

With regard to criminal justice and the police, almost all of it is local to the 18,000 police departments, all local. You know, the big national police departments—FBI is domestic, ICE is domestic, and border patrol is domestic. The border patrol kills a lot of people a year. They actually kill—this is perhaps a tangent—but they kill a lot of people from helicopters across the border, interestingly. So, there are a lot of problems in the big agencies, but most of the issues of policing are local.

And the same thing with incarceration. There are a little more than 2 million people incarcerated. About 200,000 of those people are in federal prison. The vast majority of people who are incarcerated are in local and state prisons. So, whether Trump is president or not, almost all of the changes that will matter in terms of the issues I organize around, like criminal justice and policing, are local.

My hope is rooted in seeing and being in a community with organizers across the country and activists—citizens, people who don’t identify as “organizers” or “activists”—who believe in a better world and are willing to fight for it. I just testified before the Baltimore County Council—I went to middle school and high school in Baltimore County—and the organizer that I’m working with most closely there is a seventeen-year-old. She was a student member on the school board in Baltimore County. She just graduated, and she is one of the best organizers I’ve worked with. People like her are where my hope is rooted.

Is it possible, do you think, in our country—with racism so deeply rooted—to make sustainable gains toward racial equality?

I think it is, yeah. I think that there are some people who think it’s not. I think there are some people who think that white supremacy is baked into the air, and so the best you could do is fight. I don’t believe that. I think that we can undo this. I think it has to be a full-court press. It won’t be one thing. There’s no silver bullet. It’s all of the things happening at one time. And you know, you think about your own childhood, you think about what high school was like for you. I look at high school and now I’m like, “Wow.” The clothes you wear, the way you express identity is so much freer than when I was in high school. And, definitely freer than when my dad was in high school. So, there’s a generation of people that don’t even know the constraints that other generations have grown up with.

And that gives me a lot of hope. Especially as a gay Black man. I look at the way gender identity and sexuality are [expressed by] teenagers. That to me is like, “Wow, there’s a sea change coming.” Some people are going to die out, they’re going to go, and there’ll be generations of people for whom that world of bigotry and hatred will be something they remember from other people’s memories, not their own life.

I didn’t make this about race. Racism made this about me, right? I didn’t do this. I don’t want to talk about race all day.

When the protests start to wane and donations to matching campaigns fade, how do we ensure that the conversation stays central?

I’m not necessarily worried about the conversation. The police kill a lot of people. The police kill like 1,100 people a year, right? So, you’ve only seen what, three videos so far this year? Police behavior will keep this conversation alive. That’s not what I’m worried about. I’m worried about how we make sure people pivot to solutions. That is what keeps me up at night. In 2014, we actually had no data. There was no data about who the police killed before 2013. We knew it was a problem. We knew, especially in St. Louis, the police had killed ten people, literally, while we were still protesting. So, we knew it was an issue, but we couldn’t talk about trends in suburban communities and trends in Kenosha. We didn’t know. And now, six years later, we know. I can map out where the problems are across the country. We can tell you that the police kill more people in suburban communities than almost all other communities combined. We can tell you all these things that we didn’t know before. And what we have to do is make sure that we are focusing on structural solutions that will change the outcomes. That’s the work now. It is not sexy, it is messy. You have to put a stake in the ground. Putting a stake in the ground means somebody will then get you to go far enough.

When [Campaign Zero] created #8CantWait, which is a campaign about restricting the power of the police—it’s the single largest reduction of the power of the police in US history outside of a Supreme Court case—some people said it wasn’t radical enough. Some people said they didn’t go far enough. That is the cost of putting a stake in the ground. But more people have to put stakes in the ground instead of theoretical frameworks. We know the police are killing people. We know it’s not fair. We know there’s not justice. We’ve got it. So, the question becomes, “What do we do?”

In a learning community like Bowdoin, I think it is [important] to make sure there are norms so that we frame tough conversations about race and justice so people can come, they can brainstorm. It is often messy. People are challenged, and teachers need to make sure there’s a space where people aren’t harmed. I think that it’s easier to do that in learning communities.

In a recent tweet, you talked about being invited to speak somewhere about racism, but they wanted to review your talk first.

I didn’t make this about race. Racism made this about me, right? I didn’t do this. I don’t want to talk about race all day. I have to talk about it because it impacts the way that I’m able to move through the world. And that company was a huge company too. And I’m not opposed to submitting the slides early. I get it. I know what it’s like to be a leader in a big company. But we had a prep call, and the tone was, “Please don’t stop talking about race, but we want to make sure it’s uplifting.” Racism is not uplifting. But I can definitely help people understand what we can do about it.

Amid all of this, talking about race every day, being in the national spotlight, being a target and the subject of Supreme Court cases, what do you do to refuel yourself?

I have great friends. I actually just reconnected with some Bowdoin people three or four nights ago. Daryl McLean ’07—DJ Daryl. He is not a DJ anymore, but he DJ’ed a lot of stuff and he was in my year. Emily Hubbard ’07, I talk to her a lot.

Burgess [LePage ’07] and I are still incredibly close. I talk to Burgess probably more than I talk to most people. I talk to Emily and Burgess a lot. I called Daryl; he was just on my mind. I talked to Nate Krah ’08 and Glen Ryan ’07. The Bowdoin crew. I talk to Barry [former Bowdoin President Barry Mills ’72]. I just spoke to Bob White’s class [chair of the board of trustees Robert White ’77], which was fun. So, the Bowdoin world is actually still really close to me—I’m still close.

My sister, I’m really close to. And then part of what I’ve had to learn over the past six years is that this work is not about how do I become a martyr. That’s not the goal. The goal is how do we create a community that can do good work. I understand there are some things that I’m uniquely set up to do, and I should do those. But part of my work, too, is to create a team of people, so that we all can do really good work.

I don’t necessarily feel overwhelmed, because my work is so focused on solutions—that keeps me going. Every day I wake up: “How do we fix it? What’s the next thing? Can we help cities do this thing better than they could before?”

Is there anything else you’d like to mention before we sign off?

I think we can win in this lifetime. I believe that. That’s a core belief. And some of it is rooted in Bowdoin. Bowdoin was the place where I learned how to imagine without constraints; that is true. It was Bowdoin—a place not without its faults—with so many resources, where I didn’t have to worry about basic things anymore. I could just think. The food was taken care of, housing was taken care of. If I needed help with a paper, there was a structure for that. There were all of these structures, so it actually—for the first time—freed up my mental energy to not have to deal with survival, to not have to worry about the next thing; to not have to be stressed about, “If I spend this $10, I won’t be able to buy lunch.” All that stuff was gone, and I could just dream and imagine. And that is probably the single biggest thing I’m able to bring to this work, is that I can say, “I think we can do that!” I’m able to explore all the options because I learned how to do that.

Did you know that Frank Chi ’07 and Will Donahoe ’08 have probably built every big website we’ve [Campaign Zero] done?

Did you see the #8CantWait website? #NixtheSix? All of these sites, Will and Frank built. They are our ringers. The videos we’ve put out—Will and Frank. To this day, they’re like our secret weapon.

Part of what makes it work is they just get it. I can call, I can have like an insane idea and say, “I think we should do this, and I think we should probably do it in five days.” And they’re like, “OK, let’s do it.” Their sense of possibility. It’s uniquely a Bowdoin thing. I know I stress Will out. He’s like, “DeRay, what are you doing?” But we pull it off every time, which I’m really proud of.

Ed Note: On November 2, 2020, the US Supreme Court handed down a 7-1 decision in Mckesson’s favor stemming from a Black Lives Matter rally he attended after the murder of Sterling Brown by police officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in July 2016. A police officer who was injured at the protest sued McKesson on the theory that his alleged organization of the protest made him liable for damages. A federal district court rejected the officer’s claim, but a panel of the 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that decision and allowed it to proceed, where it eventually ended up in front of the Supreme Court.

Photos: Bunni Elian

This story first appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.