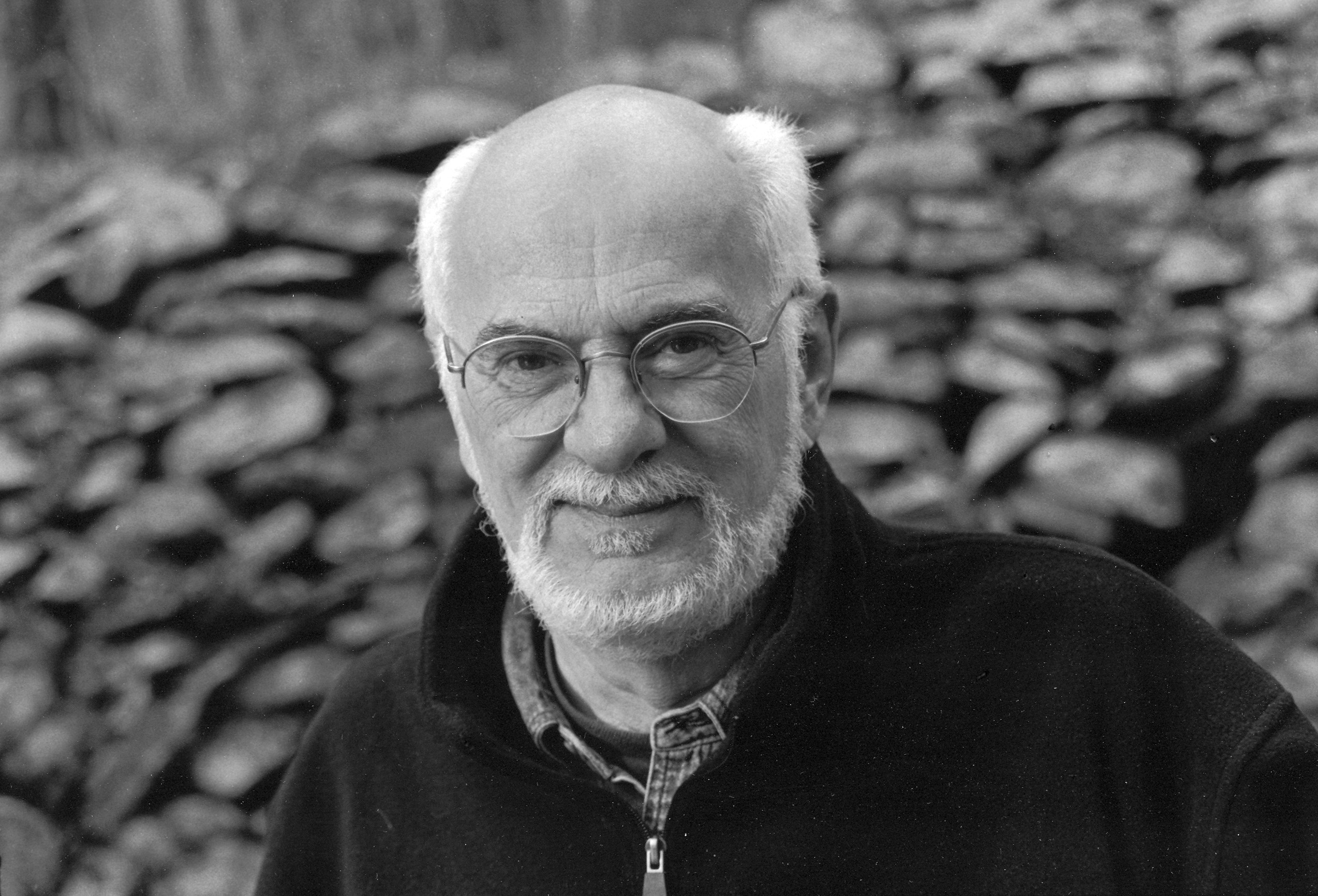

Richard Geldard '57 Talks Contrasting Decades of Influence

By Bowdoin Magazine

In the dimly remembered fall of 1953, we members of the all-male Class of 1957 arrived in Brunswick, found our rooms and mates, were chosen by a fraternity, suffered hazing, and settled in. What we did not know at the time was that these four years would mimic a singular normality in American culture and character. The next decade, the Sixties, would become forever famous as the beginning of another era that would change America forever. Those two decades would define my formal education, from Bowdoin to The Bread Loaf School of English at Middlebury, and then out to Stanford for a doctorate. As I look back now, the time of my formal education was a sequence of influences and impressions but not a time of personal control and self-knowledge. Fortunately for me, however, was that the influences were from gifted and important sources. In my Bowdoin years, members of the faculty like Athern Daggett ’25 and Frederic “Tilly” Tillotson H’46 were important. Especially Tilley, because the central focus was my four-year tenure as a member of the Meddiebempsters, the nine-person ensemble that went from barbershop four-part harmony to modern jazz with seven parts created by the absolute perfect pitch of director and arranger Terry Stenberg ’56.

In those years, highlights were the trip to Europe with the USO to serenade American troops in Germany and a moving experience at Carnegie Hall. I recall that evening in New York looking down at the worn floorboards and thinking of the great artists who had performed there. Such are little moments that stick over the years.

After Bowdoin came the army, in my case the armor school at Ft. Knox. Excellent training but not many memorable moments. Coming next of note was a return to The Taft School, my alma mater, to teach English and theater. I needed more depth in both subjects, a problem solved by Bread Loaf, a powerful experience because of the faculty assembled every summer in Vermont. It was there that I found Greek tragedy with the great translator William Arrowsmith, and Emerson with the prodigious Harold Bloom. In Emerson class with Bloom, one of his many stories involved a cocktail hour conversation he had with then Yale president Bart Giamatti, who asked Bloom how his Emerson class was going.

“Fine,” Bloom replied, “but I wish people would stop thinking of Emerson as sweet.”

“Sweet?!” Giamatti exclaimed. “He’s about as sweet as barbed wire.”

It was that, and my own subsequent study, that agreed with Giamatti’s corrective assessment.

These resources and hard work opened doors at Stanford. For example, a letter from Arrowsmith convinced TBL Webster, the world’s expert on fifth century BCE Athens, to agree to be first reader for my dissertation on the plays of Socrates. Thus, I became a theatre and classics major.

My three years at Stanford brought several major themes together: Academic discipline and idealism, the latter a term in philosophy centering on the primacy of thought and ideas, leading also to the study of universal consciousness. The late Sixties saw the influx of mostly Indian and Tibetan scholars and teachers, first to California, and then in the Seventies eastward to the aftermath of Woodstock in 1969. The task of serious scholarship in this atmosphere was to filter out the fairy dust in order to reveal principle and perhaps even reality.

My published work on early Greek thought and Emerson’s transcendentalism has been my effort to separate wheat from chaff. Many others now labor to do the same in the ongoing study of consciousness, including now in the advanced study of quantum mechanics.

During the period following Stanford I moved to New York to assume the role of upper school head of Collegiate, the oldest school in America, founded by the Dutch in 1633. One of the many bright students I taught is now my stepson, whose mother, the artist and writer Astrid Fitzgerald, is now my wife going on forty years. And it was through her friends that I was invited by Knopf to write a book to be entitled The Traveler's Key to the Sacred Places of Ancient Greece. The word “sacred” in the title was, and still is, my effort to bring the ideas of idealism front and center in a serious challenge to materialism. The work of preparing this book took several years and trips to Greece. Astrid was photographer, designer, and reader. Long hours finally completed, the book was published in 1989 and its success and positive comments set me to work on other writing projects, books on Emerson’s idealism and a series on pre-Socratic philosophy.

I consider the two seemingly divergent areas of my study and writing to be one broad exploration of non-religious transcendence centering on the nature of consciousness. Although other traditions also share this interest, I have centered my work on Greek and American transcendentalism as articulated by Emerson and Thoreau. In addition to books, I have taught online courses in degree programs and also lectured widely, a career slowed now by age and infirmity. I continue to write, however. Last year Larson Books published a novella entitled The Magdalene Gates. The history and accounts of Mary of Magdala appeared in dramatic fashion in material discovered in Egypt in 1945. Published later with the title The Nag Hammadi Scriptures, the materials included what appears to be a letter entitled “The Gospel of Mary Magdalene,” that was carefully edited to eliminate material that might challenge Roman Church doctrines. Just last year, however, Pope Francis declared that Mary of Magdala should now be called “Disciple to the Disciples,” thus lifting her in the eyes of Christians from the negative accounts of her image in the gospels. My fictional story filled some gaps in her gospel and also told a love story, which does not involve Mary!

I suppose that I will be a writer as long as these fingers can press the keys.

I don't imagine that I would be effective at dictation. Currently, I am editing a manuscript with a writing partner, Benjamin Cunningham, a renowned mediation lawyer in Austin, Texas. Ben is an expert on hermetic studies, which will fill an important gap in my own background.

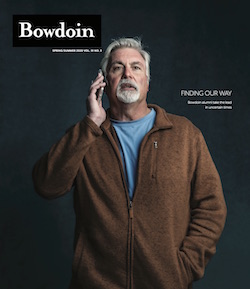

Now, as we hibernate in fear of COVID-19, we can wonder what sort of country will emerge from this crisis, what values will support our recovery, and what knowledge of ourselves as a nation we will find. I will put my trust in the young women and men of Bowdoin, and my granddaughter and friends at Mount Holyoke, to find solutions to pandemics and global warming so that they can look back as fondly as I have done at a personal life, starting as mine did among the pines of Bowdoin. A note of caution: As my late roommate Payson Perkins ’57 used to say, looking up as we walked with our dates to the stadium through those tall pines, “Look out for the pine cones.”

This story first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.