Where is Everyone? Addressing a Glaring Disparity in the Outdoors

By Rebecca Goldfine

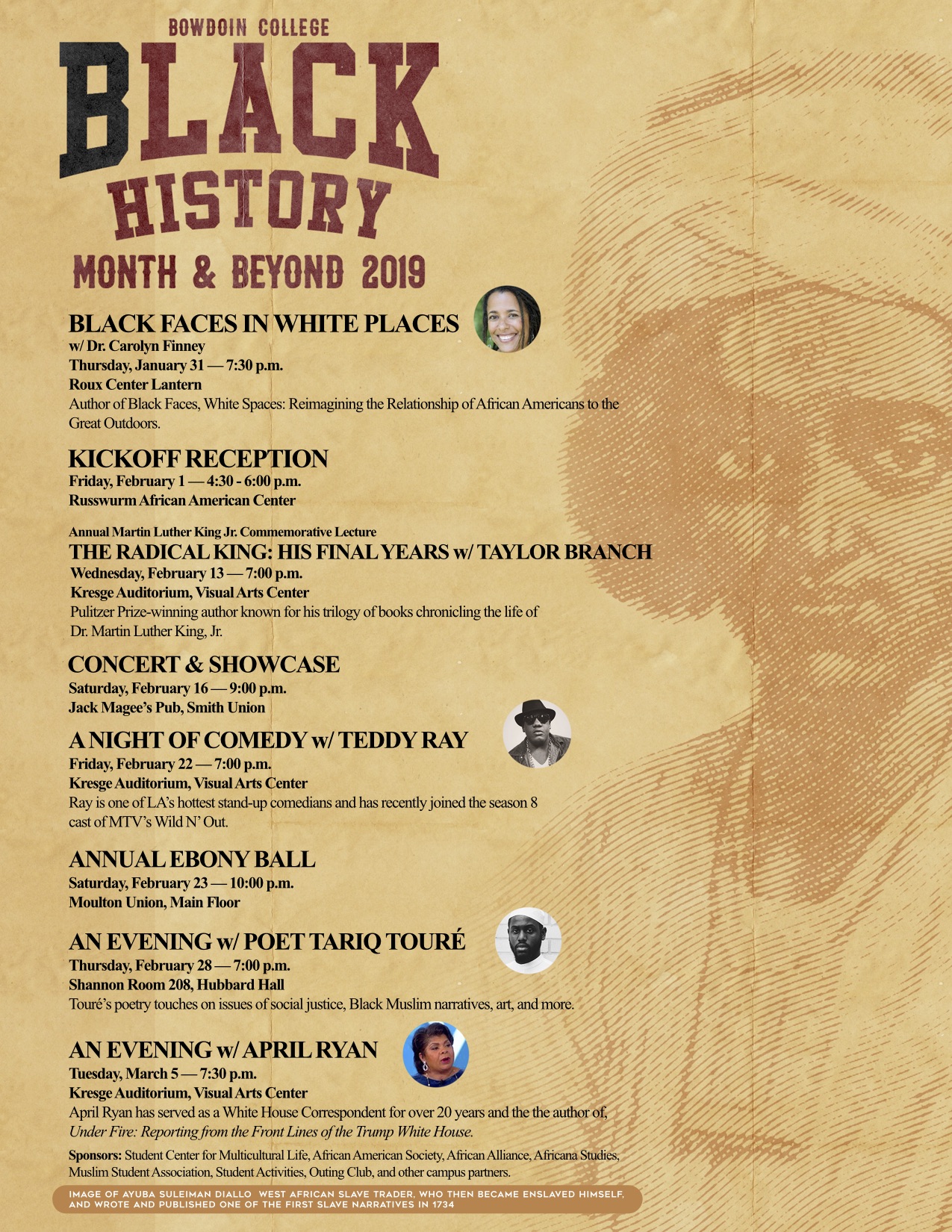

The Bowdoin Outing Club invited Finney to campus January 31 to speak about racism and the outdoors, illuminating for students both a troubling contemporary reality and its historical roots.

Finney's visit is part of the Outing Club's ongoing effort to ensure every student feels welcome inside its Schwartz Outdoor Leadership Center and outside in nature.

To achieve this, the Outing Club organizes diverse programs throughout the year, from expeditions planned in conjunction with different student clubs to campus visits by writers, activists, entrepreneurs, and filmmakers whose work touches on issues of race and the environment.

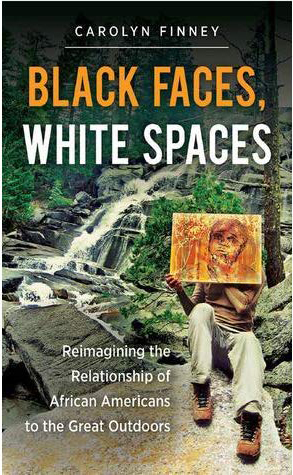

Seemingly indefatigable, Finney spent all day last Thursday—from early morning to well after 9:00 p.m.—meeting with staff, faculty, and students. She spent hours at the Schwartz Center answering the questions of students who lead trips for the Outing Club. All the club's leaders had been asked to read Finney's book Black Faces, White Spaces over winter break.

Her book argues that the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and racial violence have left lingering footprints, shaping people's ideas of who belongs in the outdoors and who fights for environmental causes. These conceptions are reinforced by, among other things, popular media and advertising.

Meera Prasad ’19, the Outing Club's diversity outreach coordinator, said she was impressed by the number of students who attended Finney's official talk.

"Her direct nature and willingness to make people uncomfortable for growth is something I hope we will keep with us moving forward," Prasad said. "What she said about just adding a few people of color to white spaces as an ineffective solution was important."

A big takeaway for Assistant Director of the Outing Club Tess Hamilton ’16 was rethinking what it means to support others who want to access the outdoors. "Her point was not about how you help other people, it's about how you can help yourself understand white privilege and where you have blind spots," she said, adding that the Bowdoin Outing Club is giving serious thought to the questions, "What are we willing to change? And how do we give students of all backgrounds a voice in shaping the Outing Club?"

Darius Riley ’19, who also attended the talk, appreciated Finney's urging people to take risks, whether that's by talking to someone from a different background or exploring a new place. "I am glad she encouraged students to get out of their comfort zone and take risks, because that is the only way we're going to grow," he said.

Tess Hamilton agreed, and appreciated Finney's communication with students. "I think the rapport and respect she was able to garner with students right away was good for the kind of conversations that we need to have to push the ball forward," Hamilton said.

Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors

To a packed audience in the Roux Center for the Environment, Finney began her talk by sharing her personal story of growing up on the estate of a wealthy family just outside New York City. Her parents worked as the property's caretakers for decades. With her two brothers, Finney "had the run of the place," playing outside among the pools, gardens, and fruit trees.

Later, after the owners had died and her parents had moved back to Virginia to a home on one-half acre, Finney's father mourned the old property, grieving, too, that he could not leave much land to his children.

"Land means economic and political power," Finney said, as she turned her focus to this country's history. "It is about legacy."

The ties between African Americans and land in the United States has always been "complicated," she said, to say the least. "First, [African Americans] were told they were property, and then they were told they could not have any land, even though they basically built the economic backbone of this country working on the land."

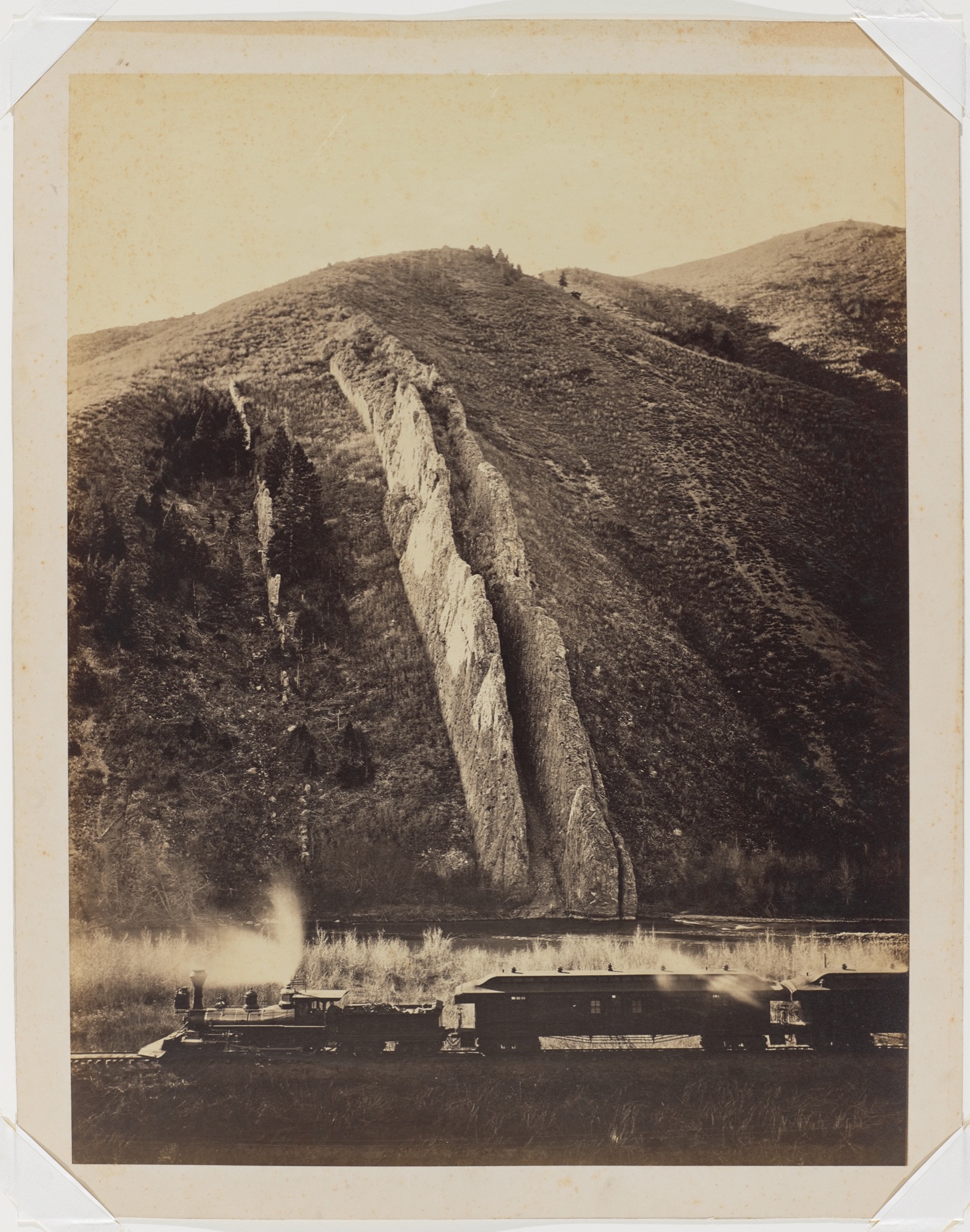

Finney laid out a stark contrast: In the early 1900s, as naturalist John Muir and President Theodore Roosevelt were chatting about conserving this country's most beautiful landscapes, black people were being lynched. Black people were also forbidden from entering many public spaces. And when the parks opened, they were not allowed in.

Finney laid out a stark contrast: In the early 1900s, as naturalist John Muir and President Theodore Roosevelt were chatting about conserving this country's most beautiful landscapes, black people were being lynched. Black people were also forbidden from entering many public spaces. And when the parks opened, they were not allowed in.

Even after the dismantling and denouncing of Jim Crow segregationist laws in the 1960s, Finney argued that African Americans remain scarred by being long dehumanized and associated with the primitive and wild—"as the state we want to move away from."

Nonetheless, Finney, noted, many African Americans throughout our history have loved, appreciated, and protected nature—in spite of legal, social, and cultural barriers. She cited as examples two extraordinary, and largely unrecognized, activists: MaVynee Betsch and John Francis.

Returning to her own life, Finney said that the story of her father and mother has also been erased from the land they cared for more than forty years. Soon after the owners sold the property, the new owner put the acres into a conservation easement to protect it from development.

The celebratory public information shared by the land trust overseeing the conservation deal made no mention of the Finneys and their years tending the land. Finney said it's likely this was unintentional.

In this way, the story of environment and race is "not about people who are good or bad—that is way too simple," she said. "It gets back to what people don't see, don't try to see, don't know how to see, and what gets lost. My parents' life evaporated just like that, and I think that is historically what we've been doing in this country."