Faculty Explore Links Between Art and the Environment

By Nicole Tjin A Djie ’21

The panel, called Art and the Environment, was convened in celebration of a current Bowdoin College Museum of Art exhibition, Material Resources: Intersections of Art and the Environment.

The event served to showcase both the art that can be found in the new exhibition, as well as the opportunities that exist for an interdisciplinary study of the seemingly separate realms of science and art.

Beginning the talk, Patty Jones revealed how art served as a core element of early ecology. Jones is an assistant professor of biology and director of Bowdoin’s Scientific Station at Kent Island. Presenting the early works of naturalists such as Marian Marien and Martin Johnson, Jones demonstrated the unmatched ability of hand-drawn illustrations to capture and communicate the complexity and wonder of the natural world.

“Drawing enables the artist to represent the plant or animal in ideal positions and lightings that aid in identification,” Jones said, explaining the unique advantage drawing has over photography. Despite this capacity of art to communicate information, scientists, in ecology specifically, have detached art from its once intimate union with science.

“With time and with technology the science of ecology has moved beyond observation and into a focus on data—particularly large datasets,” Jones said. Despite this disjunction, Jones argued that newer technology is likely to facilitate the resurgence of art as a communication tool. “We’re starting to see illustration pop back into scientific research in a way that is really lovely and exciting,” she said, highlighting images such as those of Maine artist Jill Pelto.

Following Jones, associate professor of history and environmental studies Matthew Klingle challenged audience members to think beyond our mythical notions of the frontier.

“Few words in the American lexicon are as hardy as frontier. Hijacked by jingoists, sanctioned by politicians, embellished by novelists, sanctified by politicians, dissected by academics, romanticized by tourists, and memorized by school children, the frontier has endured a century worth of debate, misuse, ridicule and neglect," Klingle began, underscoring the frontier's complex legacy in American culture, society, and intellectual life.

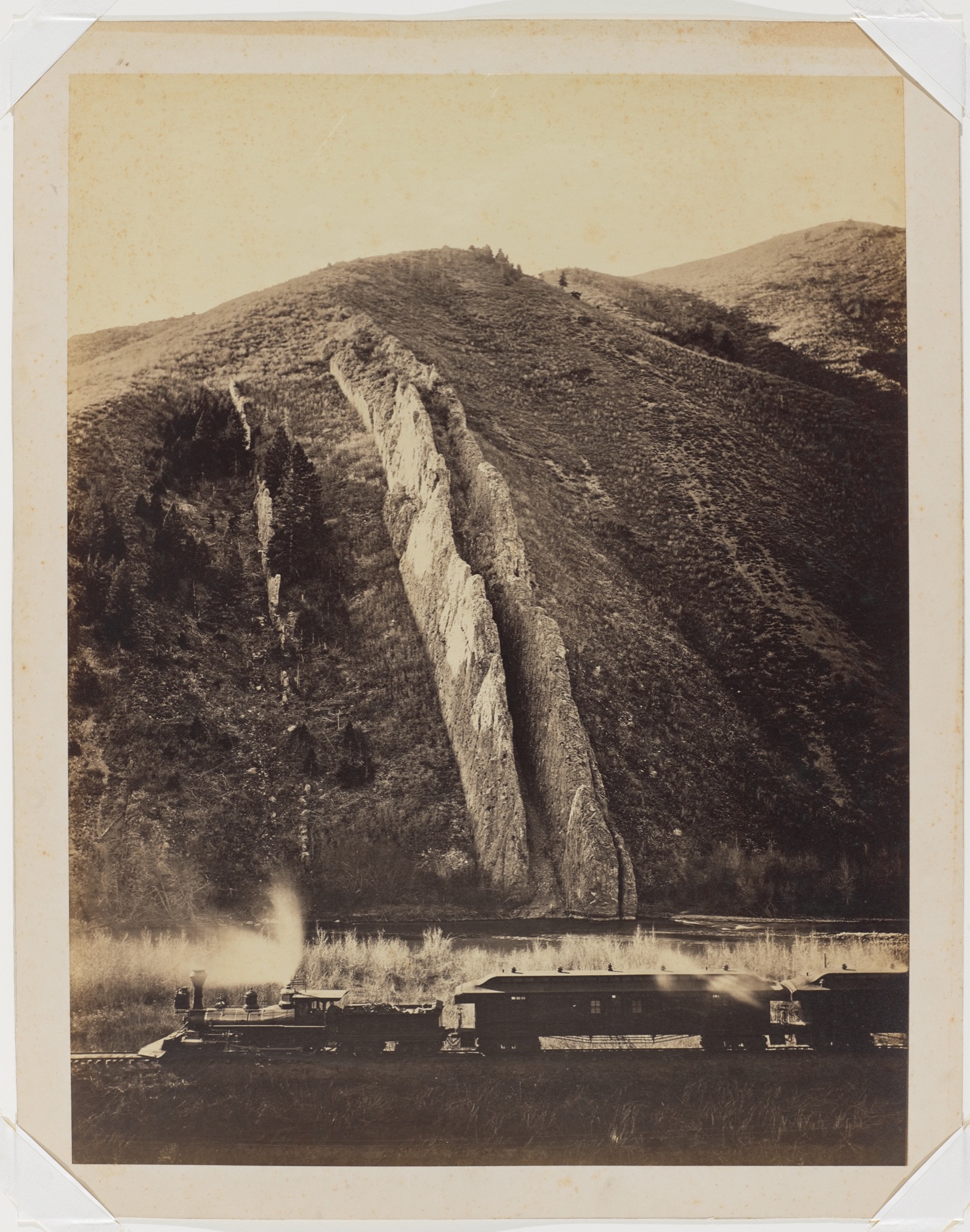

Showing grand portraits of the frontier, including Emanuel Leutze's Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, Klingle contrasted the romanticized image of the West with less stylized and more ambiguous ones captured in stills such as Carleton Watkins' Devil's Slide, a black-and-white image of a railroad in front of a massive dike.

Klingle ended with a potent last note connecting the frontier to politics.

"Thinking about the frontier is a political act," Klingle said. "I think it is time we put dirt on the grave of the idea that somehow the frontier is the only wellspring of American exceptionalism."

Ending the panel, Natasha Goldman, a teaching associate in art history, gave a talk that led audience members through several twentieth-century artists who have used materials that come from the natural environment or made art that comments on ecological aspects of the land.

In exploring "art of or for the land," Goldman discussed the works and inspiration of artists "who use natural materials for aesthetic, ecological, and/or philosophical reasons," such as Andy Goldsworthy's Holocaust Memorial Garden of Stones and Agnes Denes' Wheat Field.

All three faculty emphasized not only what they have learned from their respective research, but from their students.

Jones recalled her nights spent at the Schiller Coastal Studies Center admiring the scientific illustrations students created after a day spent in the lab.

Klingle said he had based much of his lecture on the findings and writings of his first-year seminar students.

And Goldman thanked her first-year seminar students for their research contributions related to art and environment. One of these students was Henry Zeitlow ’22 who died in a car accident in early January. Goldman praised his work and quoted from his writing as she talked about the intersection of art and the environment of St. Paul, Minn., Zeitlow's hometown.

"I learned a lot from Henry—his love of the environment, his hometown of St. Paul, his dedication to working with primary texts that bring new interpretations to works of art," she said.