Seeing the Forest: A Q&A with John Rensenbrink

By Matt O'Donnell

As he prepares to turn ninety in August, Bowdoin professor emeritus John Rensenbrink just published his most important book.

Interview by Tom Putnam ’84

Interview by Tom Putnam ’84

Your formal schooling almost ended at age fourteen in Pease, Minnesota.

That’s right. My mother did not want me to go to the public high school in town because it was not Christian. My father thought I should work on our hardscrabble farm. But then he passed away. So my older brother and I managed the farm, and my mother allowed me to take correspondence courses from the American School in Chicago. And later my amazing mother, with her limited formal education, wrote a personal appeal to Calvin College to accept me as a student.

You succeeded in college and then pursued your doctorate at the University of Chicago.

Yes, I studied under Leo Strauss, who thundered against the behaviorists who were attempting, in the 1950s, to turn political philosophy into a mechanistic science. He introduced me to all of the greats—Plato, Aristotle, Rousseau, Hobbes . . .

And you then introduced countless Bowdoin students to the same.

One lesson I appropriated from Leo Strauss was the importance of learning alongside my students. For me, the purpose of the classroom is to advance the knowledge of all who participate, including the professor.

You were considered a bit of firebrand.

I began my career at Bowdoin in the 1960s, when the campus was aflame over controversial issues such as Vietnam, civil rights, and coeducation. One year, I offered a seminar on Africa for freshmen. That was a breakthrough. “A seminar for freshmen?” and, secondly, “Non-Western studies? Are you kidding? It’s not acceptable.” But fortunately I was supported by President James “Stacey” Coles. And then with one of my students at the time, Barry Mills ’72, we started a student-taught course, which was truly inflammatory!

In 1984, in addition to teaching, you became one of the principal founders of the Green Party—nationally and in Maine.

That’s the hardest thing I’ve ever tried to accomplish—to create a new political party. For me, the Green Party and its Ten Key Values offer the possibility of creating a new economy rooted in the land and a grassroots, ecologically tuned political culture. For years, achieving this vision became my passion.

In your new book you state: “In contemplating the fact that I will not live forever, I feel life’s call. It’s not only the trees that need help. But life itself is severely threatened. Not just in me or in those dear to me. But life itself may be extinguished in the human species as a whole, my species, the one I belong to.”

Woo, that’s a good statement. Did I write that? It brings tears to my eyes because it reminds me of the challenge we face. Wow.

During these politically divisive times, it is tempting to retreat to the fringes, to focus on ourselves and our families, to tend to our own gardens, and to stay aloof from politics and the public square. What’s your response to those who are inclined to follow that path?

Read my book! In it, I recount a story from Plato’s Politics. Plato is aware of the darkness of his times exemplified by the trial and execution of his teacher, Socrates, by dishonest political authorities. He puts words in Socrates’s mouth and has Socrates describe a man who sees the wickedness of humankind and chooses to protect himself under a shelter. The man lives his own life, pure from evil and unrighteousness, and departs in peace and good will, with bright hopes. Plato has a young observer, Adeimantus, state that such a man had done a great work. To which Socrates replies, “a great work, yes, but not the greatest, unless he finds a polis which is suitable to him—where he will have a larger growth and be savior to his country, as well as of himself.”

That passage has been an inspiration to me throughout my life for its refusal to abandon politics. It is in interacting with others, Plato reminds us, that we find “a larger growth.”

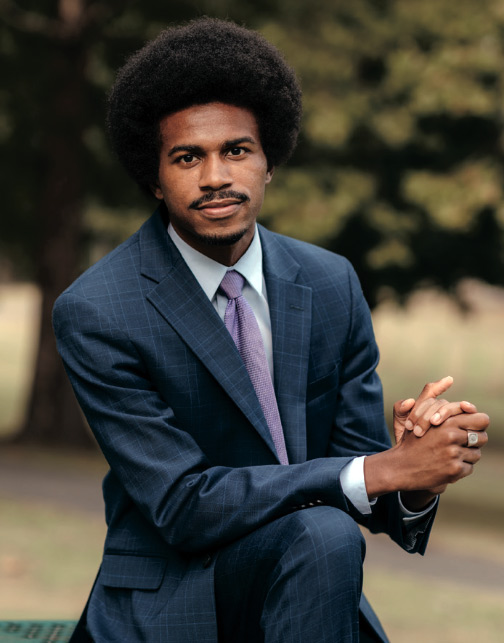

John Rensenbrink is one of seven children of Dutch-American farmers. His mother, Effie, was born in the Netherlands, and his father, John, was the son of immigrants. A highly admired professor of government and environmental studies, he taught at Bowdoin for over thirty years, beginning in 1961. He and his wife, Carla, a former teacher and university professor, live in Topsham, where they raised three daughters and spearheaded the Cathance River Education Alliance. The paperback edition of his newest book, Ecological Politics for Survival and Transformation, will be published this summer. He is a lifelong fan of the St. Louis Cardinals.

This piece first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2018 edition of Bowdoin magazine.