Professor Henry Laurence Asks ‘Can Public Broadcasting Help Save Democracy?’

Associate Professor of Government and Asian Studies Henry Laurence thinks they can. Laurence is currently working on a book about the evolution of public broadcasting in those three countries. He recently delivered a lecture at Harvard University provocatively titled “Public Broadcasting in the Age of Fake News: Will NHK, NPR or the BBC Save Democracy?” Among the threats to democracy today, he said, is a crisis in journalism brought about by, among other things, the fact that there’s simply “too much information” out there. This has fueled an increasing polarization in public opinion, Laurence argued, and spawned a growth in sensationalist, opinionated, misleading or even false journalism.

For the record, Laurence defines “fake news” as either the deliberate spreading of misinformation in a targeted and often sophisticated way,” or the selective use of information, known as “spin.” The result, he said, is a desperate need for what he called “slow news,” meaning news that takes the time to provide context, analysis and fact-checking. “There is plenty of good journalism out there,” he continued, “the problem is it’s not reaching everyone.” Too many people, he said, have stopped believing anything other than the media they like, and distrust the others.

The three public broadcasting systems analyzed by Laurence are by no means identical. They have different funding mechanisms and organizational structures, and their output varies. Japan’s NHK, for example, tends to be more conservative in its program choices and less inclined to challenge the status quo, said Laurence, while the BBC regards itself more as a government watchdog, holding politicians to account. In the US meanwhile, broadcasters like NPR and PBS are known for their innovative use of technology, reaching out to local communities and bringing the wider public back into broadcasting through the use of podcasts and the crowdsourcing of information.

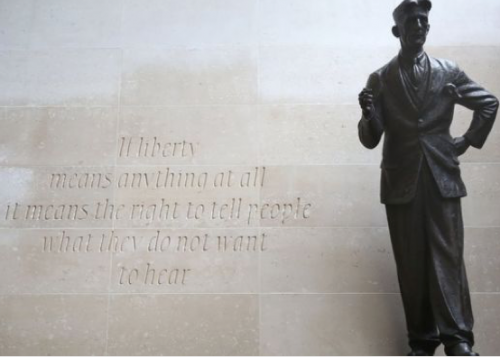

Nevertheless, Laurence continued, all these public broadcasters are bound by the common idea that media are for the public interest, and they all believe in “treating their audience as citizens rather than consumers, telling them what they need to hear rather than what they want to hear.” Public broadcasters are also required to be politically neutral, or at least fair, said Laurence, which has led to some debate over the years. He cited a watershed moment in the UK more than ninety years ago when the British Broadcasting Corporation refused to back the government side in the 1926 general strike, despite a request from Winston Churchill, a senior cabinet member at the time.

Today, concluded Laurence, public broadcasting is more important than ever and may represent some of the best hopes we have to repair some of the damage done to society by the media revolution. “[Public broadcasters] are uniquely placed to help our democracies in different ways,” he told the audience.

Laurence spoke to Harvard University’s US-Japan Relations Program on April 17, 2018. Click here to listen to the talk.