How Some (But Only Some) Church Leaders Helped Build Peace in Northern Ireland

By Tom Porter

It was an iconic image that seemed to encapsulate the senseless violence that engulfed Northern Ireland in the late 1980s. A kneeling Catholic priest gives the last rites to a dying British soldier, who had been set upon and beaten after being cornered by a mob at an IRA funeral. The priest’s face is streaked with blood where he had tried to resuscitate the man.

The clergyman was Father Alec Reid, one of a handful of church leaders in Northern Ireland who went on to help bring peace to the troubled province. The largely unsung role played by these religious leaders was the subject of “Religion and the Conflict in Northern Ireland – Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution?” —a recent lecture by Gladys Ganiel, Research Fellow in the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security, and Justice at Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Mitchell ’54, H’83 is known as the architect of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, bringing to an end thirty years of violence in Northern Ireland, during which more than three thousand people were killed. In the years prior to that agreement, said Ganiel, a few clerics on both sides of the political divide played a crucial role both in mediating discussions between the two sides, and in reaching out to their own communities to argue for peace.

Father Alec Reid

Efforts on the Catholic side were led by two priests at the Clonard Monastery in west Belfast—Reid, and Father Gerry Reynolds, about whom Ganiel is currently writing a biography. Reid’s major achievement was bringing about discussions between the extreme nationalist group Sinn Fein, the political wing of the Provisional IRA, and the more moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party, which was also nationalist but strongly opposed the violence of the IRA.

“Amidst the violence of the late 1980s,” said Ganiel, “when Northern Ireland seemed on the abyss, Alec Reid managed to persuade SDLP leader John Hume to meet in secret with Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams. The opening of this behind-the-scenes channel of communication was a crucial development in what seemed to many like Northern Ireland’s darkest hour.”

The subsequent meetings between Hume and Adams enabled Catholic nationalist leaders to develop an agenda for ending the violence which they were eventually able to present at peace talks with Protestant unionist leaders. The role of Father Reid, who died in 2013, was not revealed until many years later.

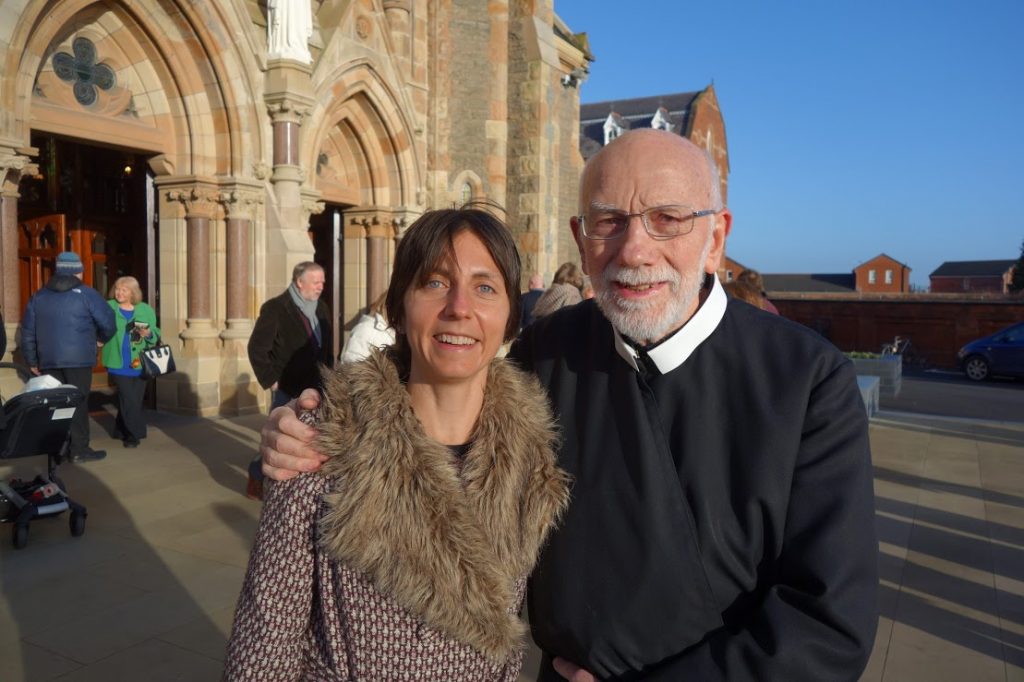

Father Gerry Reynolds

While Reid was involved in the political process, Reynolds was known for his efforts at the grassroots level, reaching out to the Protestant community, said Ganiel. “When he died in 2015, at his funeral it was said that he had visited more Protestant churches than any Catholic priest in the history of Ireland.”

Through various ecumenical initiatives, Reynolds worked tirelessly to build bridges between two historically divided communities. He established, for example, a partnership with the Fitzroy Presbyterian congregation in south Belfast, said Ganiel.

“Gerry built relationships with a number of Protestant ministers over the years, through involvement in clergy fellowships and the ecumenical Cornerstone Community. He was able to convince some of these Protestant ministers to attend secret talks with people from Sinn Fein and the IRA, which helped each side to understand the other better. As leaders in their communities, Protestant ministers were then able to prepare the wider Protestant community for compromise.

“In 1994 he built on this to start a group called the ‘unity pilgrims.’ This was a collection of Catholic worshippers who would come to Clonard monastery for mass early Sunday morning. Afterwards Reynolds would take them to visit Protestant churches and to worship there. Gerry saw the unity pilgrims as a sign of reconciliation between Catholics and Protestants, a beacon of hope to the wider community.”

Protestants for Peace

There were clergymen on the Protestant side who also fought for peace, said Ganiel. “Like some Catholics, many members of Northern Ireland’s Protestant community were political hardliners,” she said, “die-hard loyalists committed to remaining part of the United Kingdom and steadfastly opposed to the Roman Catholic Church and all it stood for. Fortunately though, they were not all like this.”

Much of Ganiel’s research concerns a group called ECONI, which stood for “evangelical contribution on Northern Ireland.” ECONI emerged during the troubles, and being evangelicals, its members quoted scripture from the bible to try and encourage people to reject violence.

“They used scripture to justify reconciliation rather than division,” said Ganiel, “and they had quite a far-reaching program. ECONI was led and staffed by laypeople, but they were also quite strategic in targeting Protestant ministers and community leaders with their magazine and educational workshops. They tried to be midwives to a process of identity change in the Protestant evangelical community.”

Does Religion Have a Role in Keeping the Peace?

There are some important lessons to be learned from the Northern Ireland experience about conflict resolution, said Ganiel. “One key point is that in situations where religion has played a role in the conflict, it also needs to play a part in the solution. Another key take-away is that you cannot make any progress until you’re prepared to talk to the practitioners of violence.”

These are not lessons that everyone has taken on board, she added. Although the peace has, by and large, held in Northern Ireland, the province remains a deeply segregated society, and the church on both sides of the divide shares some of the blame for this, said Ganiel.

“Religious leaders like those in ECONI and the Clonard Monastery played a crucial role in bringing peace to Northern Ireland, but they were outliers. It was left to individuals like Reid, Reynolds, and others, to do what the mainstream church leaders themselves should have been doing. Many say the churches lost legitimacy during the troubles, and they have a point.”

Gladys Ganiel’s lecture October 17, 2017, was sponsored by the department of Government and Legal Studies.