Borderlands: Ni de aquí ni de allá (neither here nor there)

By Students in Hispanic Studies 2306

On April 10, 2023, he visited the Spanish Nonfiction Writing Workshop class, taught by Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Carolyn Wolfenzon, to speak about some of his own short stories—“Parecetamol,” “Imagining Something Better: Rolas from my border Hi-Fi,” and “Lupe bajo las estrellas”—that often cross the border between reality and fiction.

The following day, Vaquera-Vásquez spoke to the wider Bowdoin community about his most recent book, Fieldnotes on Borderlands. Born in northern California, Vaquera-Vásquez challenges readers to reflect upon issues of identity that come with border crossing. To Vaquera-Vásquez, border crossing creates opportunities where urgent voices, a sense of belonging, art, and unique stories can intertwine to comment on the products of migration.

Other recent publications of his include Algún día te cuento las cosas que he visto (2012), Luego el silencio (2014), One Day I’ll Tell You the Things I’ve Seen (2015), and En el Lost y Found (2016).

In his work, Vaquera-Vásquez speaks to the idea of borders being multifaceted and beyond the tangible. In doing so, he refers to his own experience of feeling most at home in foreign places across the globe. He connects to the immigrant experience of often neither feeling at home in the host country nor identifying completely with their home country. He uses borderlands as a means to discuss the ni de aquí ni de allá (neither here nor there) sentiment.

Vaquera-Vásquez introduces artistic pieces that bring humanity to things that begin to feel like mere statistics—a mass migration here, an influx of immigrants there—art that brings personhood to the individual. For example, near the Tijuana International Airport, the artist Richard Lou installed a single door in the open desert where immigrants and refugees would typically make their way to the United States.

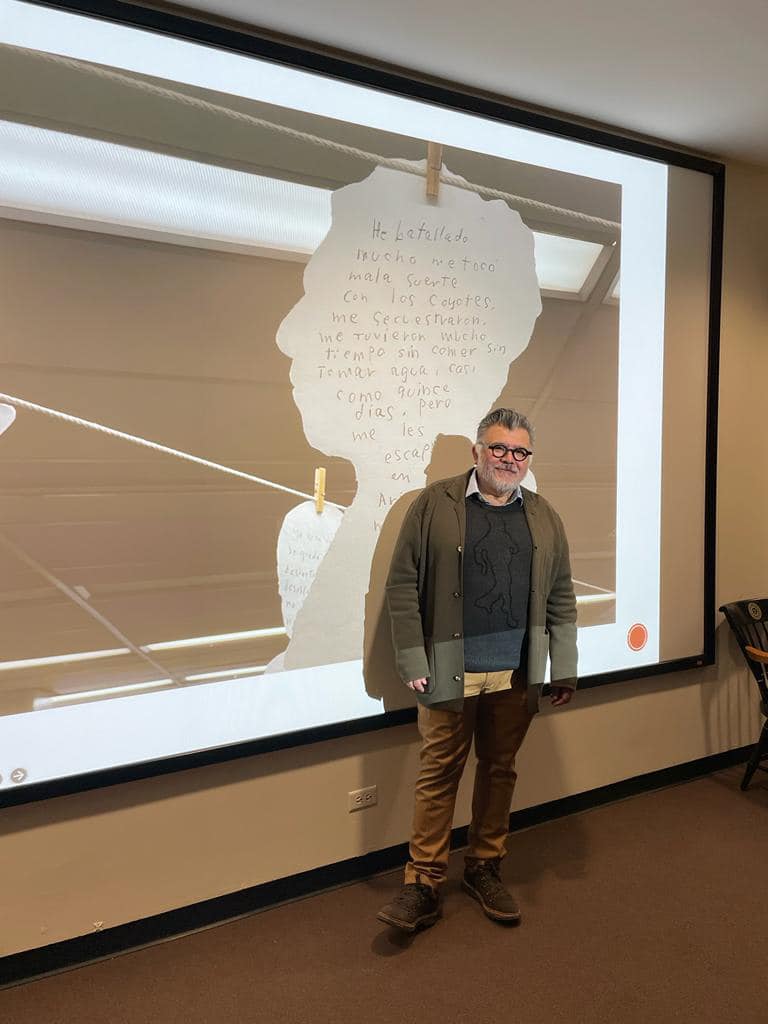

This exhibit gave an opportunity for migrants to cross with dignity. Derli Romero, another artist, put together an exhibit called Rostros Migrantes (Migrant Faces), a compilation of silhouettes with the thoughts and writings of actual migrants crossing recently from Central American countries like Guatemala and El Salvador. These silhouettes were hung on a clothesline and made from the clothes that the migrants had left behind. Written by hand and functioning almost as biographies, these give identities to the migrants, people who can be defined beyond where they have been and where they are going.

When you think of home, what comes to mind? Perhaps you imagine your childhood residence. Or maybe you associate Bowdoin with home? Maybe, like me, you are unsure. This uncertainty is a theme Vaquera-Vásquez further elaborates on with querencia. Briefly, querencia is the sense of belonging a person feels. To a person, this feeling can be brought on by the smallest of trinkets or by the largest pieces of land, evoking feelings of security, acceptance, or support. For Vaquera-Vásquez, one fragment of his querencia remains in a glass vial carrying sacred soil from Chimayo, New Mexico.

Vaquera-Vásquez also commented on being stereotyped as a foreigner at border crossings, recounting an experience where a security officer made a profane remark to him at a Turkish airport. Having traveled to various places throughout Latin America, Europe, and the United States, he had stamps in his passport from these visits, which a security officer took note of. With this observation, Vaquera-Vasquez pondered the stereotype that Mexicans are not usually seen traveling around the world.

During the lecture, I noticed his way of referring to others as Chicanos. This prompted me to ask—what are Chicanos? I have heard many definitions throughout my life: some people believe second- or third-generation descendants from Mexican migrants are Chicanos; others propose the migrants themselves are the Chicanos. I came to understand the borders in our identities and how there is no requirement to choose between sides or countries, that we can create our own space. This space Vaquera-Vásquez chooses to call the “middle ground,” which he finds on the road and in between the places he has been and the places he is going.

This talk resonated strongly with a class of students who are mostly of Latin American and Hispanic origin but who were raised in the United States, a group our professor Carolyn Wolfenzon refers to as “heritage speakers.” All our lives, we have had to grapple with the “middle ground” of coming from one culture but being immersed in another. We are sure that many can relate to this idea when we reflect on our experience at a small liberal arts college such as Bowdoin, with students coming together from a variety of different backgrounds to a small school far from home. We know now that it is possible to be both “ni de aquí ni de allá.”