Exhibition of Ancient Art to Open at Museum of Art

By Bowdoin College Museum of ArtThe exhibition explores the origins of Etruscan civilization with objects drawn from the permanent collection of the Museum.

Etruscan Gifts: Artifacts from Early Italy in the Bowdoin Collection opens to the public on February 1, 2024.

Drawn from works in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art collections, Etruscan Gifts offers a glimpse of this extraordinary culture and explores Etruscan origins, their contacts with the Greeks and contemporary cultures in ancient Italy, and their legacy that can still be felt today.

The Etruscans were an ancient people who lived in what is now central Italy between the 8th century BCE and the 1st century CE before being absorbed by the growing Roman state. In a 1st century BCE account of Rome, the historian Dionysius of Halikarnassos describes some of the mystique surrounding the ancient Etruscans and their culture.

"...the Tyrrhenoi (Etruscans) migrated from nowhere else, but were native (to Italy), since they are found to be a very ancient people and to be similar to no other in their language or in their manner of living."

Dionysius of Halikarnassos Roman Antiquities, I. 30

Where the Etruscans came from remains an unresolved mystery that continues to spark debate today. Their language does not derive from Indo-European roots and defies translation. What we do know of the Etruscans comes from ancient writers, who often were rivals and adversaries, and from the archaeological record. These sources together document a culture that emerged in central Italy at the end of the Bronze Age and became the dominant cultural and political force in ancient Italy. At their zenith in the sixth century BCE, the Etruscan city-states controlled much of the Italian peninsula from the Po River valley in the north to the Bay of Naples in the south, including the nascent city of Rome. Here, the Etruscans helped create the earliest urban structures, and established many religious and political institutions that the Romans would later acknowledge as a gift from the Etruscans.

By the first century CE, Etruscan culture had largely assimilated with the growing Roman state, and few could even speak the Etruscan language. Ancient attempts were made to preserve Etruscan history and culture for posterity, including twenty volumes of the Tyrrhenika composed by the emperor Claudius, but sadly this text does not survive. What does remain are the sites, monuments, and artifacts created by this remarkable society.

This exhibition begins with artifacts connected with the emergence of Etruscan culture during the 10th through 8th centuries BCE from a prehistoric people known as the proto-Etruscans or Villanovans, after the site of Villanova near Bologna where the early Etruscan roots were first recognized. It then turns to the arrival of the Greeks in southern Italy and Sicily and their contacts with the Etruscans. Direct contacts between the Etruscans and their new neighbors accelerated the cultural exchange but also led to increased tensions. For some, the Etruscans were viewed as unwelcome rivals and eventually threats.

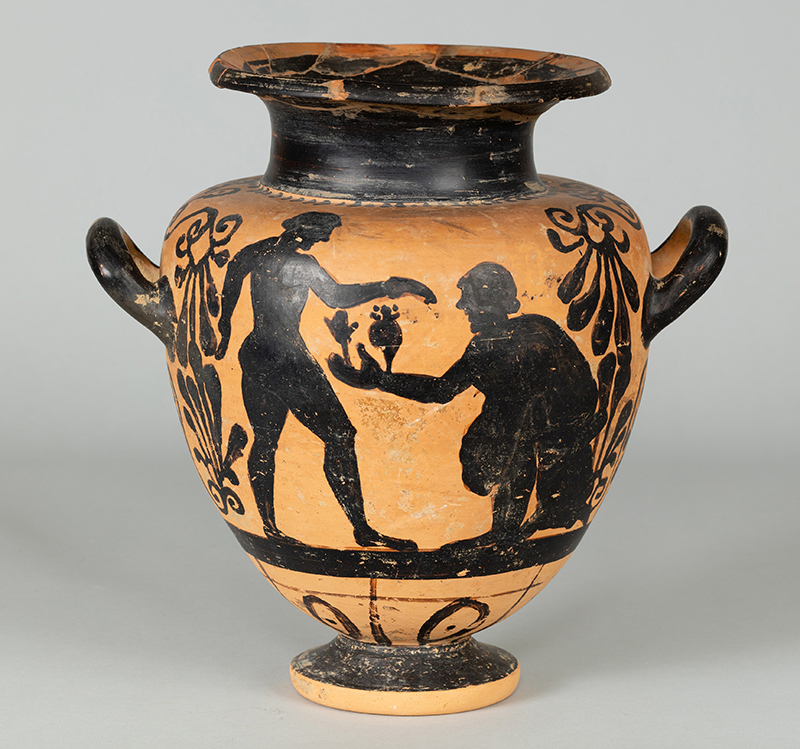

In particular, Etruscan Gifts highlights Greek figural pottery from the Etruscan tombs at Caere, modern Cerveteri. Being the southernmost Etruscan city and with access to the sea, Caere was the first to benefit from the vigorous trade for Etruscan natural resources. In return, the Caeretans received manufactured goods, luxury items in the form of metal vases, carved ivory, perfumes and particularly pottery. Vases from Corinth and Athens found a receptive market in Caere and other Etruscan cities where they served the growing popularity of banquets held in social settings and funerals.

The Etruscans were quick to learn the manufacturing processes from abroad and develop their own wares, such as bucchero, to compete with the imports. Bucchero, a black and glossy ceramic ware, is often regarded as the signature ceramic fabric of the Etruscans. While prominent in Etruscan contexts, bucchero was also exported, and examples have been found in southern France, Spain, the Aegean, North Africa, and Egypt.

With the decline in Etruscan power and influence during the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, the neighboring groups would flourish and some, like the Latins, would eventually succeed the Etruscans as the dominant power in ancient Italy.

The hilltop villages that would one day comprise the city of Rome came under Etruscan influence as early as the 7th century BCE. According to Roman tradition, Etruscan ‘kings’ ruled Rome during the 6th century BCE. It was during this latter period that Rome developed as an urban center, benefitting from new technologies and knowledge, much of which came from Etruria. The Etruscans brought their expertise in urban design, architecture, and hydraulic engineering to help create the space that would become the Roman Forum, to design Rome’s chief temple, the Capitolium, and even lay out the main sewer, the Cloaca Maxima.

The Etruscan relationship with Rome began to change in the 5th century BCE concurrent with Etruria’s general retreat in the Italian peninsula. Tables turned, and the eventual Roman conquest of Etruria did much to diminish and even extinguish parts of Etruscan culture, including their language. Still, many Etruscan gifts to Rome survived and the Romans would call them their own.

Please come and explore the world of the Etruscans at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art!

Jim Higginbotham

Curator for the Ancient Collection, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Chair, Department of Classics, Bowdoin College