Objects of the Month: Reliefs depicting scenes from "Uncle Tom’s Cabin," ca. 1870s, by Lot Torelli

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Little is known about precisely why sculptor Lot Torelli (1835–1896), based in Florence, Italy, decided to carve two high-relief marble panels depicting scenes from American author Harriet Beecher Stowe’s antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Members of the BCMA curatorial team first learned about the two panels last fall. Their excellent condition, highly skilled handling of the medium, and reference to a literary work with historic ties to Brunswick were among the reasons Torelli’s work resonated with BCMA staff. In turn, we here at the Museum were convinced that the sculptures would resonate with viewers and connect to a broad range of courses at the College.

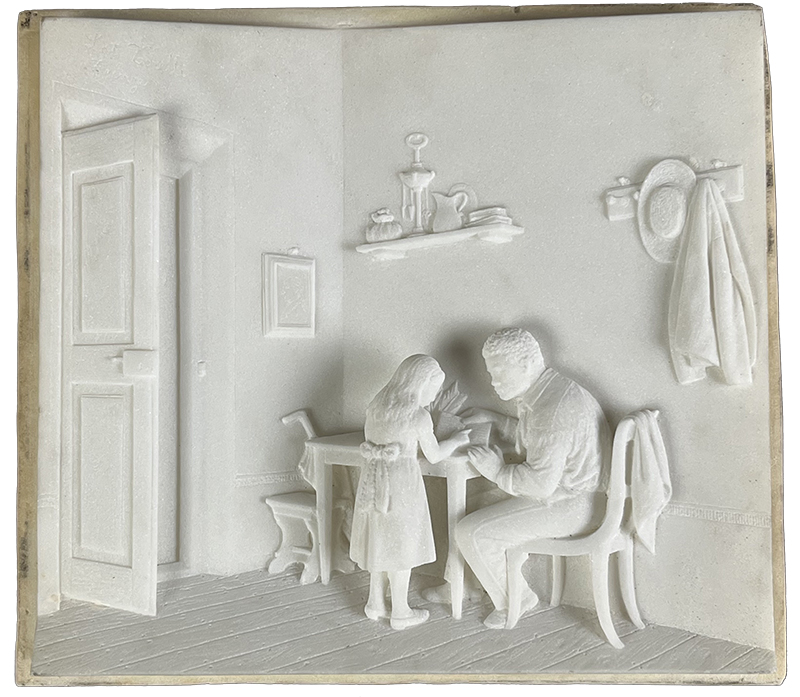

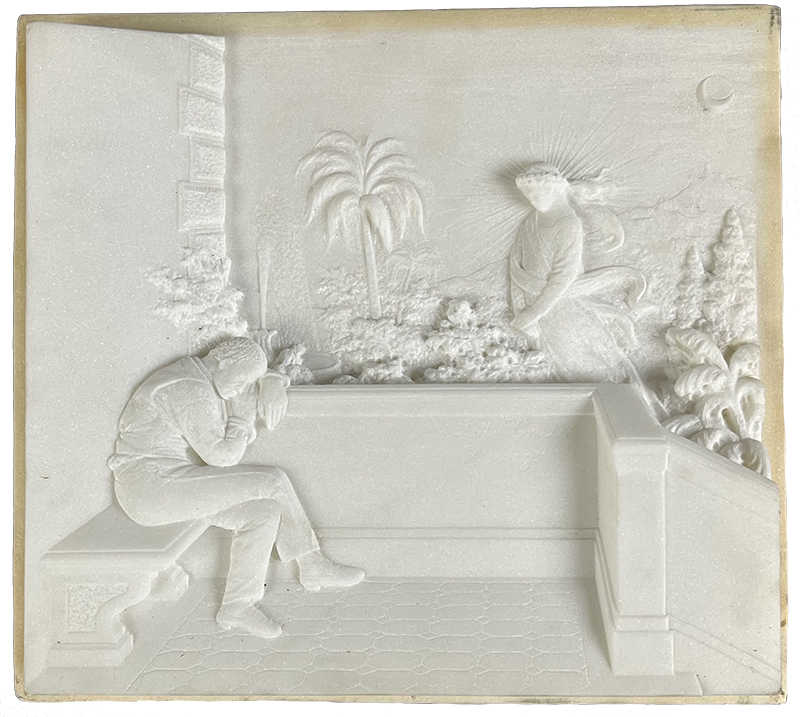

The two panels depict scenes taken from Stowe’s novel, both of which reference the friendship between two of its most frequently represented characters, “Little Eva” (Evangeline St. Claire) and Uncle Tom, the book’s eponymous protagonist. One panel visualizes a moment when the girl Eva helps Tom write a letter to his wife and children, from whom he had been separated after being sold by his former enslaver—the event that initiates the story. The second scene depicts Tom asleep and beholding a vision in which Eva appears to him as an angelic creature following her tragic death. Here, Eva appears much older and clad in classical flying drapery with a halo of light encircling her hair. The dramatic shift in her appearance signals her attainment of divine status. Together, the two panels suggest that Eva’s and Tom’s friendship transcends life and death. Torelli’s skill at sculpting reliefs pulls the viewer into three-dimensional space, as though they are participating in these two episodes, the terrestrial transpiring in a modestly appointed interior and the other—celestial— playing out on a terrace in a more ethereal setting.

The two panels depict scenes taken from Stowe’s novel, both of which reference the friendship between two of its most frequently represented characters, “Little Eva” (Evangeline St. Claire) and Uncle Tom, the book’s eponymous protagonist. One panel visualizes a moment when the girl Eva helps Tom write a letter to his wife and children, from whom he had been separated after being sold by his former enslaver—the event that initiates the story. The second scene depicts Tom asleep and beholding a vision in which Eva appears to him as an angelic creature following her tragic death. Here, Eva appears much older and clad in classical flying drapery with a halo of light encircling her hair. The dramatic shift in her appearance signals her attainment of divine status. Together, the two panels suggest that Eva’s and Tom’s friendship transcends life and death. Torelli’s skill at sculpting reliefs pulls the viewer into three-dimensional space, as though they are participating in these two episodes, the terrestrial transpiring in a modestly appointed interior and the other—celestial— playing out on a terrace in a more ethereal setting.

The 2007 Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, edited by scholars Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins, has contributed to a reevaluation of the novel and of Stowe’s legacy in recent decades, following their scorching condemnation by James Baldwin and other authors and activists during the second half of the twentieth century. As Gates and Robbins have suggested, depictions of the friendship between Eva and Tom point to nineteenth-century anxieties around forms of intimacy that crossed racial, class, and generational categories. For instance, Stowe’s description of Tom oscillates between a broad-shouldered and strong man—both husband and father—and a grandfatherly type. Visual representations of him from the nineteenth century sometimes heightened his sexuality and at other times downplayed it, especially in imagery that includes Eva. Both the hyper-virile and de-sexed renditions of Tom played into stereotypical notions of Black masculinity, which has generated some of the strongest criticisms of the novel. What is remarkable about Torelli’s sculpture is that both the carving and the material’s monochromatic light gray leave Tom’s age ambiguous. We infer that he is older than Eva mostly through his larger scale. What is more, because of the medium, the racial difference between the two figures is conveyed through indirect markers such as clothing and hairstyle rather than through the rendering of their anatomy. Viewers must rely to no small extent on background knowledge of Stowe’s narrative to understand the broader implications of the two scenes and the friendship they seek to convey.

Research into Lot Torelli’s conception and creation of these two panels is ongoing. The artist evidently had some interest in the subject: records indicate that one of the three sculptures he submitted to the 1876 Universal Exposition in Philadelphia depicted “Eva St. Clair [sic] – Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” An award-winning artist formally trained at the Art Academy of Florence, Torelli’s body of work encompassed religious and funerary sculpture, public monuments, and commissioned portraits. His use of marble, the high-relief technique, and the square format of these sculpted panels recall Italian artistic traditions such as the doors of the Florence Cathedral baptistery, crafted by Andrea Pisano and Lorenzo Ghiberti and long considered masterpieces of the early Italian Renaissance. Uncle Tom’s Cabin itself had become an international cultural phenomenon in the years following its first publication in 1852, polarizing audiences even as it inspired numerous translations, spin-offs, theatrical plays, songs, paintings, trading cards, and advertising campaigns.

These fascinating if enigmatic objects will feature in an upcoming exhibition at the BCMA, “The Book of Two Hemispheres:” Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the United States and Europe, which explores the dynamic visual culture that arose in response to what would become the most famous American antislavery novel of its era and arguably of all time. The exhibition, which will be on view from January 25 through July 21, 2024, highlights a wide array of imagery in different media, produced both in the United States and Europe, which testifies to the book’s powerful impact and to Stowe’s own international celebrity. These pictorial responses also reveal conflicting ideologies pertaining to racial difference, ideals of liberty, and Christian doctrine, which sometimes failed to translate across social and cultural contexts. The exhibition probes this complicated legacy, examining how the text and the visual interpretations it inspired reshaped conceptions of chattel slavery in the United States for publics on both sides of the Atlantic.

For Further Reading

Over the past twenty years, scholarship has been developing on the subject of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, including its major impact in the visual arts. The following suggestions for further reading are by no means an exhaustive list:

Henry Louis Gates Jr., and Hollis Robbins, eds., The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin (W.W. Norton & Co., 2007)

Catherine Hall, Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination, 1830–1867 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2002)

Jan Marsh, ed., Black Victorians: Black People in British Art 1800–1900 (Aldershot, U.K.: Lund Humphries, 2005)

Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010)

Julia Thomas, Pictorial Victorians: The Inscription of Values in Word and Image (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2004)

Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780–1865 (New York: Routledge, 2000)

Sean Kramer, Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

image: Relief depicting scene from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ca. 1870s, marble by Lot Torelli. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Laura T. and John H. Halford Jr. Art Acquisition Fund.