On the Road: BCMA’s Dirck Vellert drawing illuminates Tudor Splendor

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

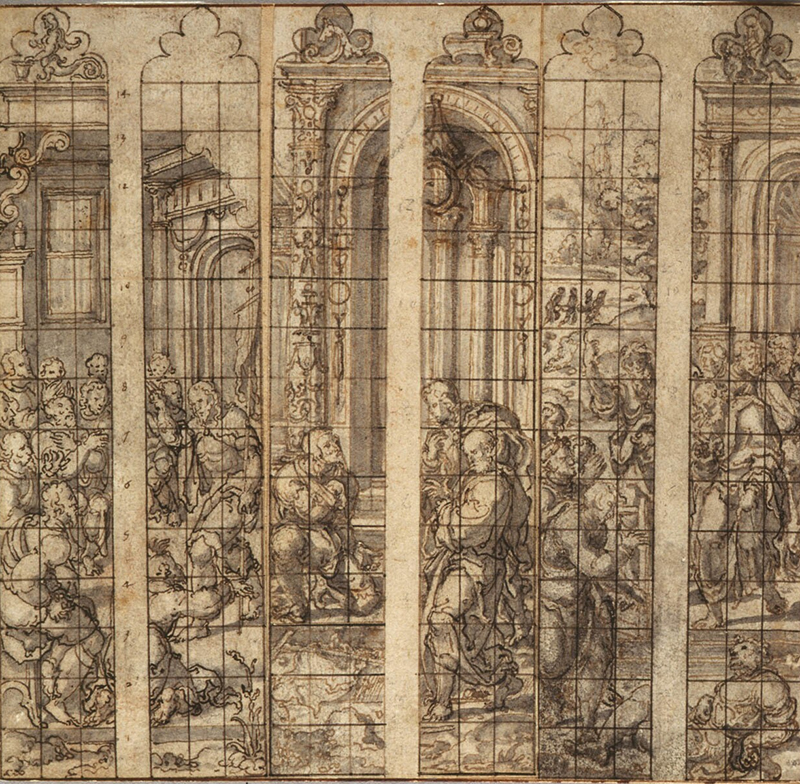

Three Designs for Stained Glass Windows, 1538, pen and brown ink, grey wash over black chalk by Dirck Vellert, Flemish, ca. 1480/85–ca. 1547. Bequest of the Honorable James Bowdoin III, Bowdoin College Museum of Art. 1811.109

Earlier last fall, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England. The exhibition, which is now on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art and which will travel to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in June, brings together a sumptuous array of figurative and decorative arts forged during a volatile and bustling dynasty. Included among the iconic paintings and grand tapestries is a beloved treasure from Bowdoin’s own collection—Dirck Vellert’s Three Designs for Stained-Glass Windows in King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, ca. 1528. Not only does the drawing represent a rare extant example by the most renowned stained glass artist of the period, it also serves as a testament to the Tudors’ political and cultural ambitions, as well as the transnational networks of production that defined the vibrant artistic traditions under the Tudor court.

Sabrina Lin '21 recently spoke to the exhibition’s co-curator, Elizabeth Cleland, Curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

SL: Could you describe how this exhibition came into being?

EC: My primary area of research and specialty as a curator is post-medieval European textiles, but my great love and main area of research has always been sixteenth-century tapestry. I come to the sixteenth century in Northern Europe very much aware of these splendid material cultures—the overwhelming impression of coming into a place like the Tudor court, and being enveloped by glorious monumental wall hangings, seeing the goldsmith’s work, the silver, the arms and armor, the manuscripts, the jewelry. But of course, above all, these extraordinary personalities captured in the great paintings of the period. That’s where all this really came together: you had the great paintings, but you also had all those sumptuous decorative arts.

One of the joys of working here at The Met is that we have all these different areas of curatorial expertise. I had done another loan show about eight years ago, which was primarily a French tapestry show. So, when that exhibition came down in 2015, I already started thinking about, “Well, what’s the next project going to be? And wouldn’t it be nice to maybe cross the Channel?” The Northern Renaissance tends quite rightly to focus in on the Burgundian territories and the Hapsburg lands. As for what’s happening in England, so many people have heard of the Tudors, but we tend to fixate on the tabloid headlines. Often the art gets less press, and there is this sense sometimes that England was somehow struggling to catch up with the rest of Europe, that the art wasn’t quite as good, they weren’t as interested, or they weren’t spending as much money, whereas actually nothing could be further from the truth. I worked with my colleague Adam Eaker, who is a curator in our European paintings department, to try and redress that balance a bit.

SL: How did you discover the BCMA’s Vellert drawing? Were you aware of it prior to your research on the show?

EC: I’ve known your drawing for quite a long time now. There was an exhibition back in London at the Victoria and Albert Museum called Gothic: Art for England, and that on viewe just as I was finishing my Ph.D. The drawing is small, but it’s so compelling and beautifully designed. It’s Dirck Vellert and has this lovely, sinuous line of a highly intelligent, sensitive draftsman and designer. It was also very rare, being one of the few drawings surviving associated with the great King’s College Chapel glass project. In terms of Tudor glass, that Vellert drawing is a superstar. It also speaks so much to one of the central themes of our show, which is about how art traveled. It wasn’t just artists crossing borders and coming into England to do their work, but sometimes the artists are remaining in their home countries—in this case, Vellert is staying in Flanders—but artists’ drawings and their works are the pieces are travelling, and it embodies that ability to send designs across the sea.

EC: I’ve known your drawing for quite a long time now. There was an exhibition back in London at the Victoria and Albert Museum called Gothic: Art for England, and that on viewe just as I was finishing my Ph.D. The drawing is small, but it’s so compelling and beautifully designed. It’s Dirck Vellert and has this lovely, sinuous line of a highly intelligent, sensitive draftsman and designer. It was also very rare, being one of the few drawings surviving associated with the great King’s College Chapel glass project. In terms of Tudor glass, that Vellert drawing is a superstar. It also speaks so much to one of the central themes of our show, which is about how art traveled. It wasn’t just artists crossing borders and coming into England to do their work, but sometimes the artists are remaining in their home countries—in this case, Vellert is staying in Flanders—but artists’ drawings and their works are the pieces are travelling, and it embodies that ability to send designs across the sea.

SL: Do you have any insights as to why surviving drawings of stained glass of this nature are so rare?

EC: It’s a bit of a parallel with my work on tapestries in that these drawings really are working tools. They’re not being made for some dilettante connoisseur collector to gaze upon and then paste into an album and keep safely. They’re made precisely to travel these great distances, to share an artistic vision in such a way that a whole team of other artists—in this case the cartoon painters of the stained glass panels—can translate them into the massive scale of the actual stained glass. They’re made to be used, to be handled, to be looked at, passed from one person to another. A piece like this we could maybe envisage might also have ended up in Henry VIII’s hand as a sort of vidimus for him as the ultimate patron, to get a sense of what he was going to see with the stained glass he commissioned. But I think, first and foremost, it was for use between Vellert and Antwerp and his compatriots based in London, who were going to be the ones actually executing it in glass.

SL: I find it fascinating that Vellert wasn’t widely credited with the design until further scholarship was discovered. Was that common in terms of the mode of workshops and stained glass production?

EC: When we’re looking at stained glass production in Antwerp in the mid-sixteenth century, which is the great center of what we used to call the Renaissance in the North, Vellert was celebrated as this incredibly talented, wealthy, successful designer and glass painter. When Albrecht Dürer visits Antwerp, he makes sure to note in his diary that he has dinner with Vellert. In that context, Vellert was associated with a project if we still have documentation. That’s a big if, because, of course, with intervening wars and so forth, we’d lost a lot. What’s happening in England at this period is complicated because we’ve got so much of this business of bringing in designs from elsewhere, and then having the journeymen who are based in London being the ones to translate it into the medium. A lot of scholars looking at the actual windows, which still survive in King’s College Chapel, have said stylistically this looks like Dirck Vellert, which would be great because he is the de facto, most celebrated glass artist of the period. But where we do have the documents, it’s people like Barnard Flower who are the ones actually named in the accounts. Therefore, the drawing is the key—that’s why it’s great to have it in the show.

SL: What was the process of physically installing the drawing and fitting it into the gallery space and overall design?

EC: In broad strokes, what Adam and I wanted to do was not just present to our visitors this lovely dialogue between decorative and painted arts, but we also didn’t want to just tell a history and illustrate it with works of art. Instead, we wanted to take a step back and present the material thematically. The first gallery was called “Inventing a Dynasty,” which introduces this idea of the Tudors’ precarious hold on the Crown, that they’re very much a parvenu, nouveau riche, up-and-coming family who didn’t really have terribly legitimate claims to the Crown. So that’s setting the tone and showing how one of the things they do is spend a lot of money on art in order to craft this sense of majesty around them. Then the second gallery, which is where your drawing was, we called “Splendor” and we really wanted to give our visitors a visceral sense of being in a Tudor palace, bringing together all the different media.

I really love that moment on the shorter wall of that gallery just dedicated to the stained glass, which is so important—this idea of sunlight filtering through colored glass on a massive scale, telling a figurative narrative that was really feeding into the Tudor propaganda machine, but also showing that the Tudors had such logistical pull and so much money that they could commission this massive project out there in Cambridge, which, at that date, was very much out in the provinces. To try and get a sense of that in the gallery was quite tricky, because obviously we’re not going to be able to bring in King’s College Chapel. What we didn’t want to do was use facsimiles or modern media to replicate. We wanted to stick to the sixteenth century art. Therefore, on that shorter wall we had your drawing, and then, set next to it in a recess, the Vellert window, not from the King’s project but from around the same date. The installation helps visitors who could stand eye to eye with the drawing and the window to interpret how you could see the designers’ hand in both media.

Sabrina Lin '21

Curatorial Assistant and Manager of Student Programs

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Illustration:Installation view of The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England on view October 10, 2022–January 8, 2023 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo by Anna Marie Kellen, courtesy of The Met.