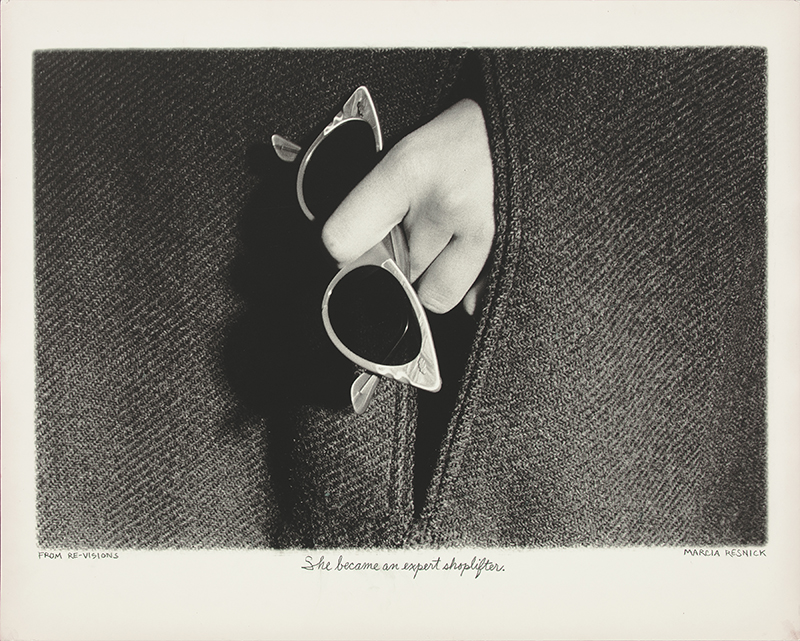

Marcia Resnick: As It Is or Could Be

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

She became an expert shoplifter, from Re-Visions, 1978, gelatin silver print inscribed with graphite, by Marcia Resnick, The Michael G. and C. Jane Wilson 2007 Trust.

Marcia Resnick (American, born 1950) was a significant figure in the extraordinary, now-mythic, creative community in downtown New York during the 1970s and early 1980s. Part of a new bohemianism born out of a rejection of the cultural establishment and sheer youthful exuberance, she embraced the camera as her primary expressive tool. Like other innovative artists of the period, she discarded the idea of what her chosen medium was supposed to do and proposed new ideas for what it might be. Applying paint and graphite directly on the photographic image, adding text elements, interjecting humor, and conceiving photography as a type of performance were some of the strategies she explored.

In the ten years between 1973, when Resnick graduated with an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts, to 1982, she was one of the most actively engaged photographers in New York, creating more than a dozen photographic series and earning a reputation among the city’s cultural cognoscenti for her irreverent wit and artistic originality. Needing to earn a paycheck, she contributed work to various magazines, became a staff photographer at the Soho Weekly News, and taught photography part-time at various schools. Her photographs were exhibited periodically and were beginning to be collected and reviewed.

And then, rather abruptly, this period of productivity ended. The closing of the Soho Weekly News in March 1982, together with several personal setbacks, led to a decline in her creative work. Only thirty-one years old at the time of the newspaper’s demise, Resnick found herself suddenly entering into a new phase of her career.

And then, rather abruptly, this period of productivity ended. The closing of the Soho Weekly News in March 1982, together with several personal setbacks, led to a decline in her creative work. Only thirty-one years old at the time of the newspaper’s demise, Resnick found herself suddenly entering into a new phase of her career.

In 2009, twenty-seven years later, on the recommendation of photographer Charles Gatewood, another friend from the 1970s, Resnick met gallerists Deborah Bell, Paul Hertzmann, and Susan Herzig. Recognizing the quality of her work, they decided to begin representing her. She had never had a gallerist before. It was shortly after Resnick’s inaugural exhibition with Bell that I learned about her work. Other museum curators and collectors also discovered her then as well, including Casey Riley at the Minneapolis Institute of Art and Lisa Hostetler, formerly of the George Eastman Museum. As no museum exhibitions nor retrospective catalogues had previously been developed, the three of us talked and decided to work together to change that.

From the beginning we appreciated Resnick’s commitment to rethinking what a photograph might be. She was on the scene in New York in every imaginable sense and had captured much of its texture while somehow remaining just beyond the notice of most people outside of New York’s avant-garde. Examining her work over the last several years has confirmed our belief that her unorthodox approach to nearly every facet of her artistic practice—including a distaste for self-promotion—made her both a vital innovator and an uneasy challenge to established narratives of photographic history. To paraphrase the song from The Sound of Music: How do you solve a problem like Marcia Resnick?

The answer, of course, was to dive into the extraordinary source material she had archived. In just over a decade, Resnick produced a body of work that spans experimental, conceptual, documentary, and editorial photographic practices, including four distinctive photographic artist’s books. Grappling with themes at once intimate and intellectual, feminist and anarchic, deploying both image and text to achieve her aims, her work from this period traces the arc of the political, social, and cultural realities that defined a pivotal era in American life. That she was at the center of so many consequential movements and social networks was no accident; she had an active role in shaping our understanding of that era, whether we knew it at the time or not. She was, and remains, an artist’s artist, operating with a high level of understanding about the priorities of the establishment and the need for radical, unapologetic intervention. She was from a generation born into a culture inundated with images and also suffused with skepticism.

In her artistic practice, she moves forward from the stripping away of imagery characteristic of Minimalism and Conceptual art towards a new type of art in which performance played a crucial role. Deployed as imp and devil’s advocate against mainstream culture’s unexamined assumptions about the medium of photography, she used the camera to probe the complex relationship between reality and representation, first in art, then in personal identity—particularly for women. Her work suggested that identity is not necessarily organic and innate, but negotiated within and around social constructions of gender, race, and sexuality. As such, “self” might be performed rather than possessed and playfully tailored for the camera—and the indeterminate audience who received its products.

The influence of television, as well as experimental theater, film, and performance is also vital to appreciating her artistic practice. To Resnick, the popularization of television in the 1970s had transformed the popular imagination in ways that she regarded as ominously anti-intellectual: “In a culture where the only book people read is the TV Guide and where Bibles are no longer made of paper and ink but are manufactured by SONY and Panasonic, the aesthetic experience can now be attained without suffering the arduous task of turning pages.” The result was a generation reared in a liminal zone of still and moving photographic images. Ever the educator, Resnick found meaning and clarity even in the apparent decline of book culture and in a new generation’s pursuits. As she suggested about punk rock in 1978, “what these kids are doing is appropriating the styles for making their statement that they see on television. You know, this is the TV generation. Ten years ago, the people that were in rock groups were not reared on television.”

Marcia Resnick’s art forged a path through the minefield of late twentieth-century image overload, finding hope, possibility, and humor in the social chaos it inaugurated. Neither the world photography nor that of contemporary art was quite ready for what she had to say, although many avant-garde artists took it to heart. Today, in an accelerated global culture dominated by pixels and wi-fi, her trenchant, eloquent work is even more powerful. We are delighted and grateful to pay tribute to her formidable contributions.

Frank Goodyear

Co-Director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Illustrations:

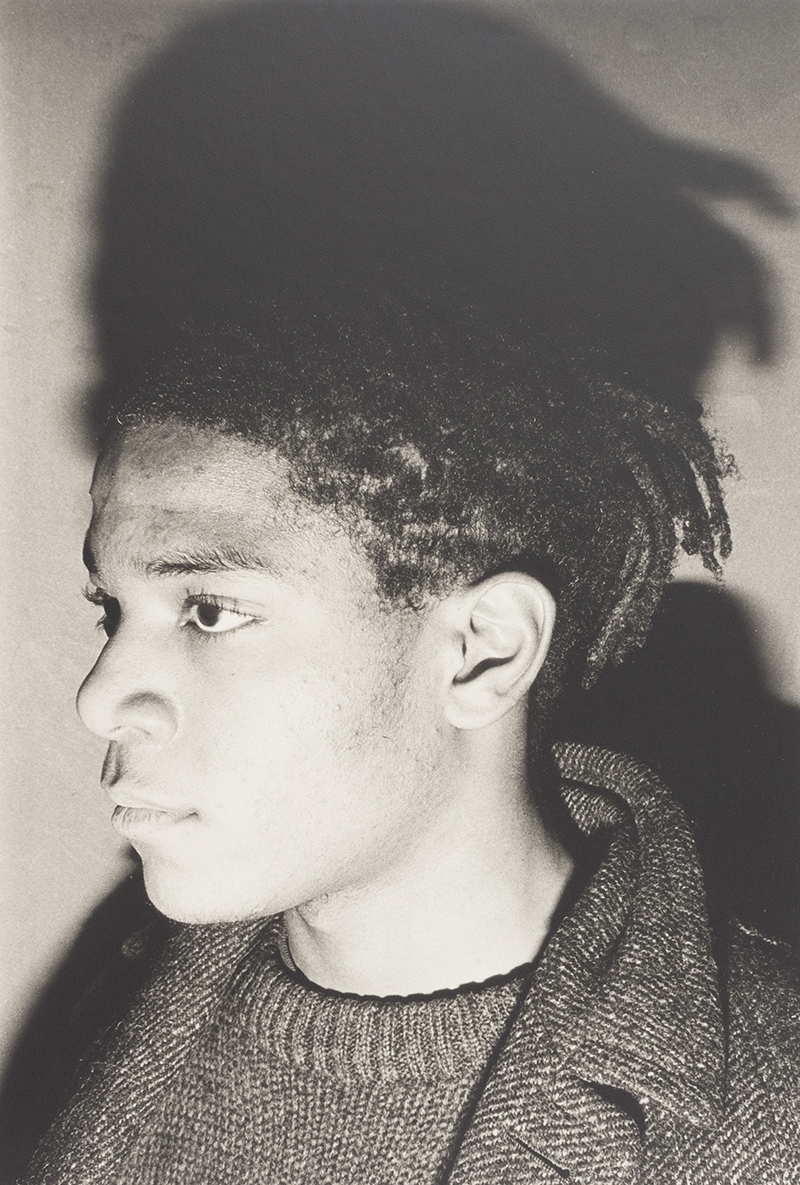

Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1979, gelatin silver print by Marcia Resnick. Museum Purchase, Gridley W. Tarbell II Fund. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

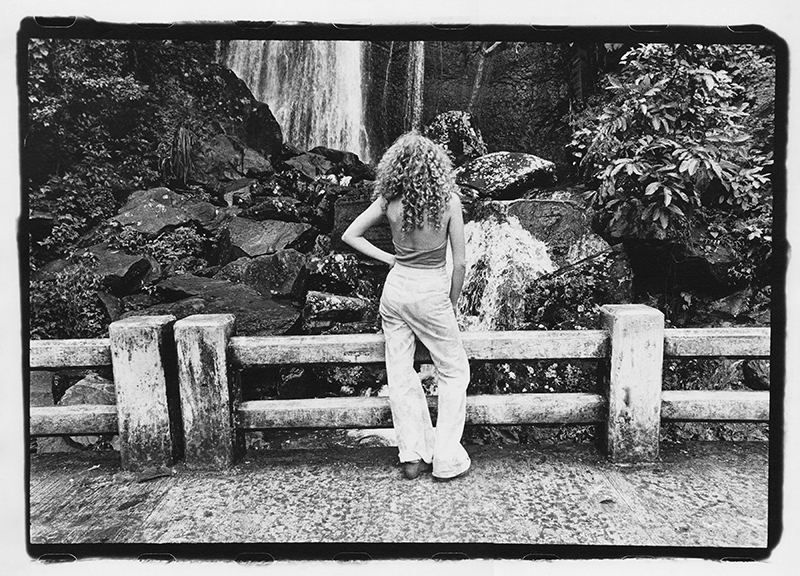

See #4, 1974, gelatin silver print by Marcia Resnick. Courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art.