Marcel Duchamp’s "The Green Box"

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box), 1934, by Marcel Duchamp, American, born France, 1878–1968. Gift of Anne d’Harnoncourt and Joseph Rishel. Bowdoin College Museum of Art. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Association Marcel Duchamp.

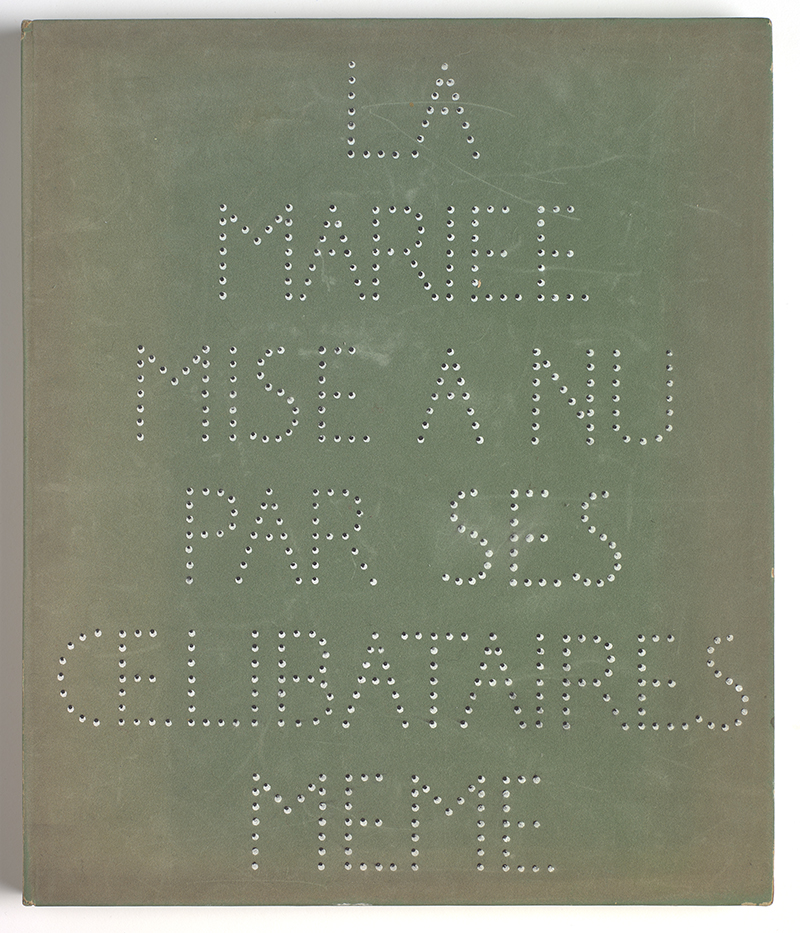

In September 1934, Marcel Duchamp published his compilation of notes, La mariée mis à nu par ses célibataires, même (La boîte verte), or The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box) through the offices of Edition Rrose Sélavy, named for Duchamp’s infamous female alter ego. Popularly known as The Green Box, refecting the color of the flocked cardboard container Duchamp used, the publication appeared in an edition of 300, complemented by twenty “deluxe” versions. The object served as a complement to or, as the artist would have it, a “guide” for a work that at the time lay in fragments in the Connecticut barn of his friend Katherine Dreier: The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). The two works, then, constitute two parts of a single whole. The union between them becomes even clearer when their full names are articulated in Duchamp’s native French: La mariée mis à nu par ses célibataires, même (La boîte verte) and La mariée mis à nu par ses célibataires, même (le grande verre). “Verte” quite literally took the place of “verre” in 1934 upon the publication of the Box, the color Green alluding to the Glass through a clever pun.

Known today through its installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the work is famous for the network of cracks that run through its upper and lower registers, a testimony to the painstaking work Duchamp did to repair the object after it shattered, presumably in transport following its first installation at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1926. But if Duchamp succeeded in repairing the object, the reconstructed work, while transparent, remains largely opaque, offering few cues in and of itself regarding the narrative embedded in it, aside from the playful title given to it by the artist. Readers of French may recognize in its title, which alludes to the disrobing of the bride by her suitors, a homophone in the final word “même,” which, read aloud, might also be “m’aime,” for “loves me,” suggesting the presence of yet another participant in the complex narrative involving the bride and her would be partners.

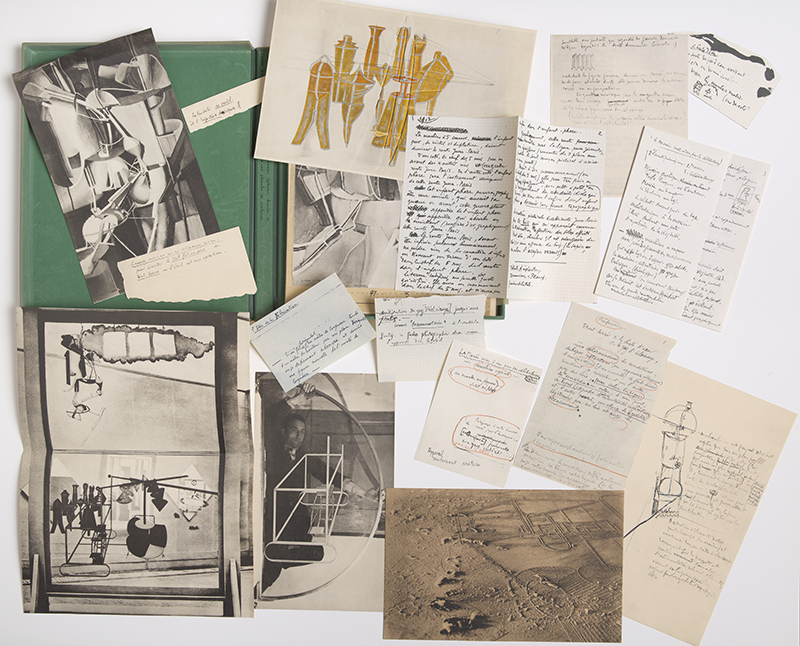

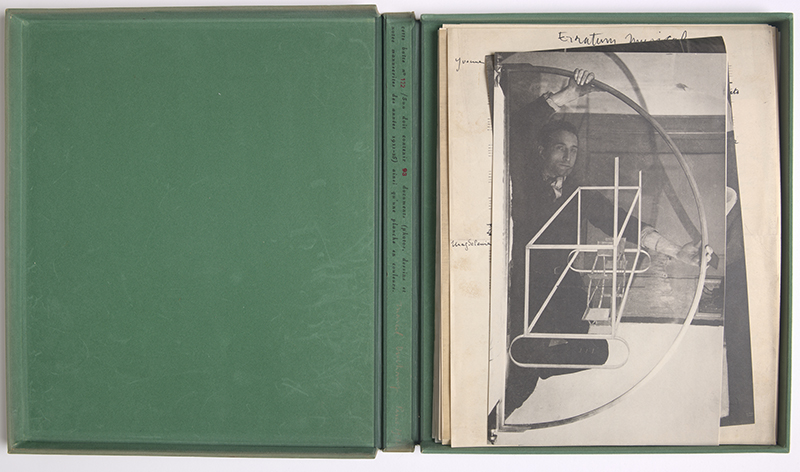

It is in fact to The Green Box that one must turn to discern the tale of unrequited love and frustrated desire that fills what Duchamp described as his “hilarious picture” with its abstract renditions of a group of nine “bachelors” who attempt, through the offices of a mechanized device, to seek union with the bride who floats above them with her garment unfurling in the firmament. The details of the narrative are recorded in the 93 notes that occupy Duchamp’s Box, apparent scraps of paper of varying lengths recording details about the object, the dynamics represented within and related thoughts. But what is most striking and surprising about the object is the extraordinary care that Duchamp relished on the production of his edition of the notes, each one of which features meticulous facsimiles of handwritten scraps of paper, preserving the torn edges of some and the inkblots left on others. If The Large Glass resists the appearance of the hand, The Green Box is intensely personal, with almost fetishistic attention to preserving the personal touch.

Intriguingly, Duchamp did not provide an order for the notes. While one note appears with the heading “Preface,” providing the preconditions for the operation of the mechanical device he has envisioned to connect the bride and the bachelors (“Given: First the Waterfall/ Second, the Illuminating Gas”), the scraps can be read in any sequence the reader pleases. The abundance of notations which suggest the rich array of metaphorical associations the artwork had for the artist has led to a remarkable volume of interpretations of the object.

But while The Large Glass remains a source of tremendous interest, it is to The Green Box itself that generations of artists and scholars have returned. It is within the box that Duchamp offers hints about the interpretation of his “readymades,” artworks created by transforming a manufactured object into something new through the addition of an apt phrase, and thus creating a new chain of associations with the object and thus transforming it into something new. It is through The Green Box that Duchamp’s interest in the construction of perspective and the implications of multi-dimensional geometry and other scientific thinking becomes clear, not to mention his sense of humor.

But while The Large Glass remains a source of tremendous interest, it is to The Green Box itself that generations of artists and scholars have returned. It is within the box that Duchamp offers hints about the interpretation of his “readymades,” artworks created by transforming a manufactured object into something new through the addition of an apt phrase, and thus creating a new chain of associations with the object and thus transforming it into something new. It is through The Green Box that Duchamp’s interest in the construction of perspective and the implications of multi-dimensional geometry and other scientific thinking becomes clear, not to mention his sense of humor.

Implicit within The Green Box is Duchamp’s own commitment to the power of ideas to shape and reshape the world around us by providing new contexts and new connections. It is also a tribute to Duchamp’s recognition of intellectual contributions to be made by artists and his commitment to an art that did not recognize only the tangible products of artistic labor, such as prints, photographs, paintings, or sculpture, but also the importance of its intellectual labor, and the fabrication of ideas.

The Green Box, while among the most celebrated of Duchamp’s “boxes” was not his only such project. His Box of 1914, which included early documentation of The Large Glass, and his À l’infinitif , or In the Infinitive, of 1966, also known as The White Box, included another host of observations about The Large Glass and related projects. His Boîte-en-Valise (De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy), or Box in a Valise (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy), 1935–1941, consisted of a miniature museum of his works to date. Such boxes, and particularly The Green Box, would go on to inspire many more generations of artistic “boxes.” As Jasper Johns noted in a 1960 review of the first English-language translation of The Green Box: “In reviewing this book, I searched for the cartoon whose caption was, ‘O.K., so he invented fire—but what did he do after that?’” Evidence of its widespread impact also includes include Andy Warhol’s “Time Capsules,” a variety of “boxes” created by Fluxus artists, and, perhaps most recently, the boxed Skowhegan Ephemera Collection, 2022, created by the artist Marc Swanson, on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and recently donated to the BCMA.

As we reflect upon the many artists whose practice Duchamp would help inform, a word is in order about the special provenance of the BCMA’s Green Box. The work, number 122 of 300, comes to the Museum through Joseph Rishel and Anne d’Harnoncourt. A highly regarded curator and director, respectively, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), the couple had a special connection to Duchamp. It was Anne d’Harnoncourt who would co-curate, with Kynaston McShine, the first posthumous retrospective of Duchamp’s art in 1972, and it was she who helped oversee the top-secret installation at the PMA in 1968 of Duchamp’s final art works: Etant donnés, 1. la chute d’eau/ 2. le gaz d’éclairage, or Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas. With a title drawn specifically from the “Preface” to The Large Glass, Duchamp’s Etant donnés, and unveiled only posthumously by request of the artist, Duchamp’s posthumously revealed masterwork testified to the critical role of The Green Box in the artist’s thinking throughout his career. At the same time, Duchamp demonstrated the pattern of revelation and concealment implicit with the notations contained within The Green Box. Both its provenance and its influence to date testifies to the important network of artistic practice and scholarship with which this special work of art interconnects the Museum. Its mysteries and its insights await further discernment though the ongoing engagement it invites with its entry in the collection of the BCMA.

Anne Collins Goodyear

Co-Director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Illustrations:

The cover of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box), 1934, by Marcel Duchamp, American, born France, 1878–1968. Gift of Anne d’Harnoncourt and Joseph Rishel. Bowdoin College Museum of Art. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Association Marcel Duchamp.

Detail of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box), 1934, by Marcel Duchamp, American, born France, 1878–1968. Gift of Anne d’Harnoncourt and Joseph Rishel. Bowdoin College Museum of Art. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Association Marcel Duchamp.