"There is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art" opens in September

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Opening September 16, 2021, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art will present There Is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art, a new exhibition examining the representation of Black women in the United States over the past two centuries. Drawing on more than sixty works of art, historical objects, and artist books both from the Museum’s collection and on loan, the show will confront the history of marginalization and make visible the presence of women of color in the history of American art. The show will feature works by a number of important twentieth- and twenty-first-century artists, including: Elizabeth Catlett, Alma Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems, Betye Saar, Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker, Mickalene Thomas, Ja’Tovia Gary, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Nyeema Morgan. Supporting these works are a selection of artifacts and ephemera, as well as nineteenth century works of art, that highlight the continuity of experiences of Black women in America.

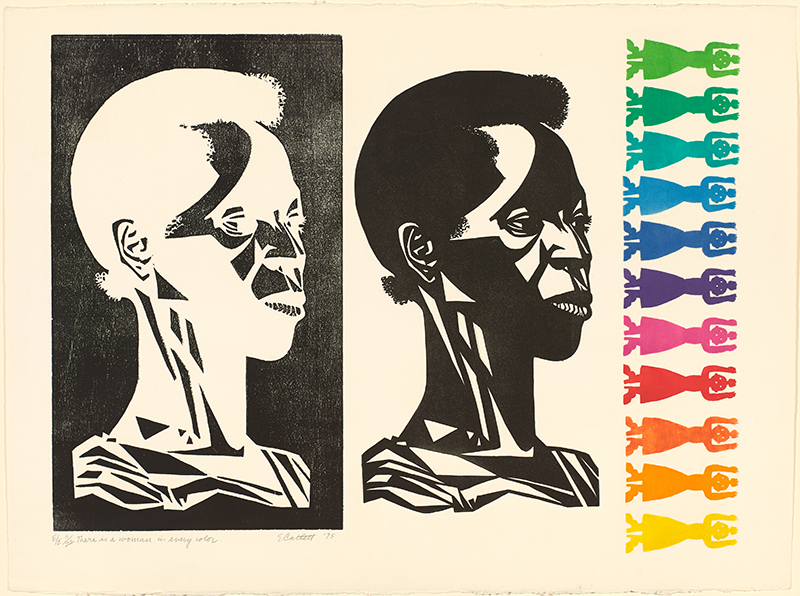

The title of the exhibition is inspired by African-American artist Elizabeth Catlett’s work There is a Woman in Every Color, 1975. Through its doubling of a Black woman and its inclusion of multicolored women, the work testifies to the multiplicity of women’s voices, which is one aim of this exhibition. Curated by Bowdoin College alum Elizabeth Humphrey, the Museum’s Curatorial Assistant and Manager of Student Programs, There Is a Woman in Every Color is constructed around six thematic sections: portraiture; the Black female nude; documented histories; labor; artistic exploration; and the influence of literature.

By beginning with portraits, viewers start with the foundational issue of visual representation of Black women from the nineteenth century and moving into the present. These works will also help audiences understand the ways in which Black women were categorized and assessed, as well how they chose to represent themselves, where and when they could. For example, the folk artist William Matthew Prior’s 1843 painting Mrs. Nancy Lawson–one half of a pair of portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Lawson—depicts her as the proper and prosperous wife that she was. However, the work also draws on the same conventions of dress, pose, and demeanor that Prior would likely have used with any sitter of the period—conventions defined by Lawson’s white peers. Moving into the modern and contemporary era, by contrast, Mickalene Thomas’s 2016 Tell Me What You’re Thinking takes the opposite approach, embracing and centering the personality of the Black woman in the photograph, with a distinctive style and setting.

By beginning with portraits, viewers start with the foundational issue of visual representation of Black women from the nineteenth century and moving into the present. These works will also help audiences understand the ways in which Black women were categorized and assessed, as well how they chose to represent themselves, where and when they could. For example, the folk artist William Matthew Prior’s 1843 painting Mrs. Nancy Lawson–one half of a pair of portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Lawson—depicts her as the proper and prosperous wife that she was. However, the work also draws on the same conventions of dress, pose, and demeanor that Prior would likely have used with any sitter of the period—conventions defined by Lawson’s white peers. Moving into the modern and contemporary era, by contrast, Mickalene Thomas’s 2016 Tell Me What You’re Thinking takes the opposite approach, embracing and centering the personality of the Black woman in the photograph, with a distinctive style and setting.

In the second section, on the Black female nude, the works explore the ways in which artists—especially male artists and, too commonly, white male artists—have fetishized the Black (female) body. Contrasting photographs by Bill Witt and Deana Lawson illustrate this dynamic clearly. Witt’s 1948 photo Black Nude and Radiator features a Black woman with her body in profile, leaning against a white painted radiator set between two white, shaded windows. Yet the woman is unnamed, and her face is turned away from the camera—perhaps from shame, or maybe because her identity was not considered relevant. Nearly six decades later, photographer Deana Lawson’s work Sharon (2007) might at first seem like a repetition of Witt’s earlier work: it features a Black woman standing nude against a radiator, in profile, in a room with white shaded windows. Yet Lawson’s work confidently upends the gaze-at-the-nude approach of Witt’s work: her model is named in the title of the piece, Sharon—and Sharon looks confidently back at the camera, an active participant in her own portrait.

The third section and fourth sections look at the lived experiences of Black women as captured in photography and material culture, and both historical and contemporary labor roles often occupied by Black women. A pair of items from the Bowdoin Special Collections & Archives address both the labor and representational issues at the heart of how Black women were often depicted. As one example, the Narrative of Phebe Ann Jacobs, Or “Happy Phebe,” written by Mrs. T.C. Upham in approximately 1850, tells the story of Ms. Jacobs (1785–1850), an enslaved person who was brought to Brunswick, Maine by the family of Bowdoin’s then-president. The title of the small booklet already conveys the author’s assertive assumptions about the status of this woman, who had been enslaved since birth—evoking stereotypes of Black people as “happy” with their subservient place in the world. This is compounded by the drawing on the same page of a small, fenced cottage, with the caption “My little house has become a palace.” Shifting from the narrative to the more tactile recall of Ms. Jacobs’ labor is the presentation of the thimble she used for her sewing work, for the benefit of the Allen family.

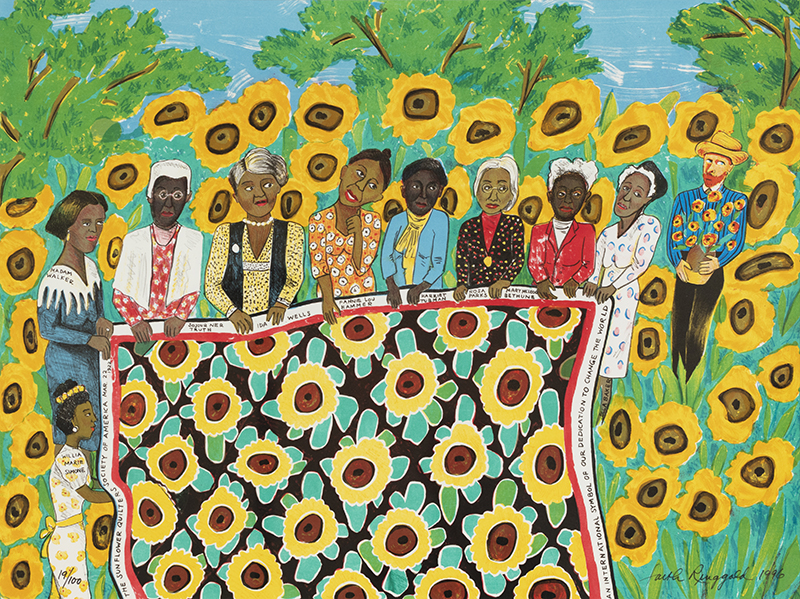

The last two sections focus on modern and contemporary art, and in particular works by Black women artists. In the fifth section, objects demonstrate how women artists approached their artistic practices, and underscores the importance of historical representation in this context. Works such as LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photograph Grandma Ruby and J.C. in Her Kitchen 2006 or Faith Ringgold’s 1996 lithograph The Sunflower Quilting Bee At Arles place Black women in images as in control of their situation, across a range of times, places, and contexts. The final section further highlights works by Black women artists who draw inspiration from literature in a variety of forms, whether from English poetry, nineteenth century American novels, short stories by Zora Neale Hurston, or major newspapers. Additionally, many artists in this section work in the art book tradition, bring their own perspective and creative approaches into this format.

The last two sections focus on modern and contemporary art, and in particular works by Black women artists. In the fifth section, objects demonstrate how women artists approached their artistic practices, and underscores the importance of historical representation in this context. Works such as LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photograph Grandma Ruby and J.C. in Her Kitchen 2006 or Faith Ringgold’s 1996 lithograph The Sunflower Quilting Bee At Arles place Black women in images as in control of their situation, across a range of times, places, and contexts. The final section further highlights works by Black women artists who draw inspiration from literature in a variety of forms, whether from English poetry, nineteenth century American novels, short stories by Zora Neale Hurston, or major newspapers. Additionally, many artists in this section work in the art book tradition, bring their own perspective and creative approaches into this format.

“It is my hope that this exhibition will encourage audiences to engage with artists often overlooked in the canon of American art, providing space for their works to stand on the equal footing they so deserve” said Elizabeth Humphrey ’14, the exhibition’s curator. “In developing this exhibition, the Museum has recently acquired several works to address gaps in our collection that this exhibition made visible. I am pleased that this exhibition will travel with the support of Art Bridges. Sharing this exhibition with communities outside of Maine helps broaden the reach of the artists represented and allows other audiences to engage in discourse around Black women’s experiences in the arts.”

There Is a Woman in Every Color will run through January 30, 2022. After premiering at Bowdoin, a condensed version of the exhibition will travel to three additional venues, with support provided by the Art Bridges Foundation, which is dedicated to expanding access to American art across the country.

Illustrations: Mrs. Nancy Lawson, 1843, oil on canvas by William Matthew Prior (American, 1806–1873). Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont.