Letters between Winslow Homer’s Parents Gifted to the BCMA

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

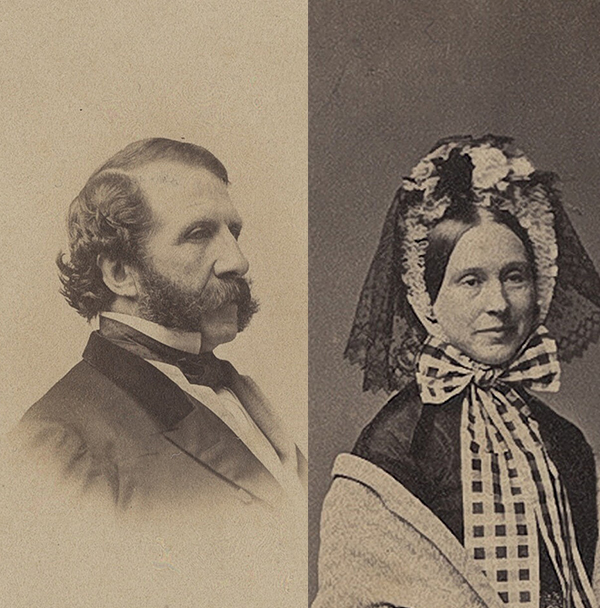

Photograph of Charles Savage Homer Sr., Winslow Homer’s Father and Photograph of Henrietta Benson Homer, gifts of the Homer Family. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

Earlier this spring Brad Willauer, a descendant of artist Winslow Homer from Prouts Neck, Maine, presented the BCMA with a collection of twenty letters between Henrietta Benson Homer (1809–1884) and Charles Savage Homer (1809–1898). The letters have never been published, nor studied before by scholars. In fact, they may not have been read by anyone since the time when they were written in the 1830s and 1840s. The BCMA is deeply appreciative of this generous gift by Willauer and his family.

This group of letters joins the BCMA’s Winslow Homer Collection, the largest archive of primary source materials related to the life of the artist. This collection was begun in 1964 with a gift of materials from Doris Homer and has continued to grow over the past six decades. Now fully digitized, the collection is often studied by Homer scholars.

Over the last two months, BCMA student assistant Kate McKee ’22 and BCMA co-director Frank H. Goodyear have worked to transcribe the twenty letters and to research their contents. In the following essay, McKee describes the collection and writes about the excitement and challenges associated with working on this group of letters.

Henrietta Benson Homer was born in 1809 as one of the nine children of Sarah Buck (1785–1826) and John Benson (1776–1862) of Bucksport, Maine. Charles Savage Homer was also born in 1809 as one of the eleven children of Eleazer Homer (1761–1847) and Mary Bartlett (1770–1844) of Boston. Henrietta and Charles married on June 6, 1833, and the couple had their first child, Charles Jr., a year later in 1834. Their second son, Winslow, was born in 1836, and their third and final child, Arthur, was born in 1841. Even as young parents, Henrietta and Charles were often apart. While Charles attended to business in Boston, Henrietta often stayed in Bucksport with her family. As described in the letters, she had ample support from her many siblings and area friends to help care for herself and the young children.

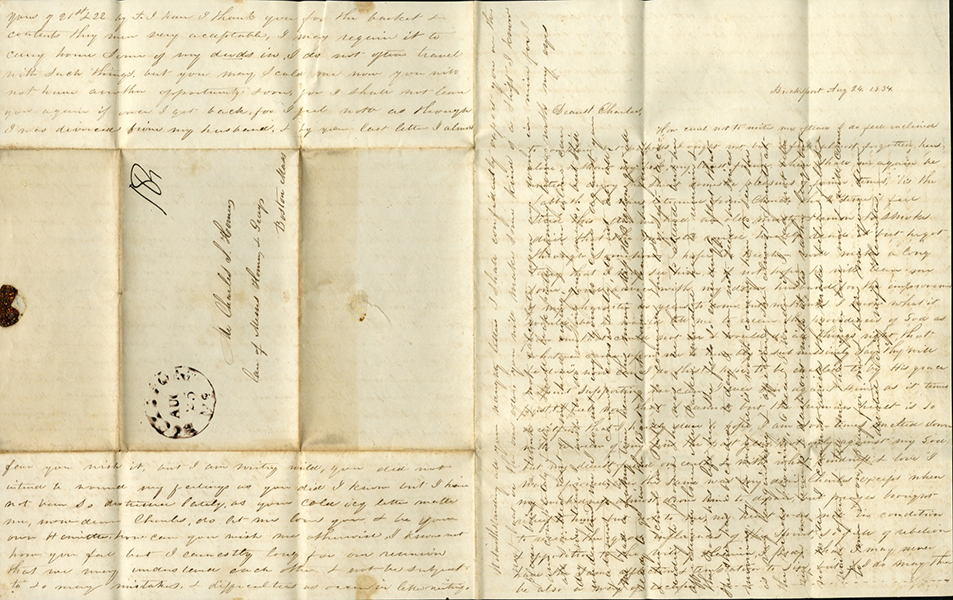

The twenty letters span fifteen years: the first letter from Henrietta to Charles is dated July 21, 1834 and the last letter is dated November 24, 1849. Fourteen of the letters are from the summer of 1834, two years before Winslow’s birth. All but one of these letters were written by Henrietta to Charles, and most were written in Maine. The letters are all written on a single sheet of paper, often on both sides. To fit even more on the sheet, Henrietta would write vertically on top of the horizontal script. The letter addressed to Henrietta was a group letter penned just after New Year’s festivities in Brooklyn, New York, in 1844 by multiple members of her family, including Charles Homer, Maria Benson, Philomela Rollo Benson, and perhaps others.

The twenty letters span fifteen years: the first letter from Henrietta to Charles is dated July 21, 1834 and the last letter is dated November 24, 1849. Fourteen of the letters are from the summer of 1834, two years before Winslow’s birth. All but one of these letters were written by Henrietta to Charles, and most were written in Maine. The letters are all written on a single sheet of paper, often on both sides. To fit even more on the sheet, Henrietta would write vertically on top of the horizontal script. The letter addressed to Henrietta was a group letter penned just after New Year’s festivities in Brooklyn, New York, in 1844 by multiple members of her family, including Charles Homer, Maria Benson, Philomela Rollo Benson, and perhaps others.

Details of Henrietta’s early life appear in the letters, including previously unknown information about her schooling. In one letter, Henrietta recalls her time “at Bradford,” revealing that Henrietta spent time in Massachusetts at the Bradford Academy, a co-educational school that prepared young people for Christian missionary work. Henrietta enjoyed a lifelong interest in painting and drawing, and many examples of her watercolors are represented in the BCMA’s collection. Unfortunately, there is no mention of her artistic interest, perhaps because she was raising three young children during the period when she penned these letters.

Henrietta writes about various people, and while Frank and I have been able to identify some of these individuals, many questions about with whom Henrietta spent her time are left unanswered. Some of the names are easy to trace as members of the Benson family. Henrietta mentions her brother Frederick and her sister Clara on multiple occasions. Others, however, are equivocal. An “Aunt Peggy” comes up recurrently, a woman who tends to the new mother Henrietta with cabbage leaves and grass oil during a period when she was sick; a month later Henrietta buys her a “lady-like” hat from town. Another mysterious character is “Margarite,” perhaps a household servant, whom Henrietta contemplates dismissing on multiple occasions. Other people from Bucksport, such as “Dr. Beecher” and “Ms. H. Bigelow,” are mentioned intermittently, attesting to Henrietta’s presence and involvement in not only her family’s affairs but also in the wider Bucksport community. Unfortunately, Winslow is only mentioned once, which was disappointing, as we had hoped at the outset of the transcription project to learn more about Henrietta’s influence on her son’s artistic work.

I have immersed myself in the study of these letters, giving careful attention to both the major and minor events in the letters. Henrietta’s writing style is by no means concise; she writes in a stream-of-consciousness style, reflecting her often-scattered thoughts. Reading each sentence is a dive into her mind, from a full-page passage demonstrating her devotion to religion to quips about a dearth of letters from Charles. Henrietta’s loose, casual, and adoring writing paints a portrait of a dedicated mother and wife who possessed a witty sense of humor, everyday grievances, a wide social circle, and incredible strength in the absence of her husband. These letters are important not only because Henrietta was the mother of three successful men, but also because they give us an intimate view into the life of a woman in the early days of Maine’s statehood. Henrietta’s writings give her a distinct voice independent of her sons.

Transcribing each letter was like stepping back into Henrietta’s world, and the close connection I feel to Henrietta has grown out of reading her unfiltered musings. I clung to each and every word of the small, cursive script, which was often difficult to decode. Working with the letters was like attentively listening to the stories of an old friend. Each sentence describing Charles’s absence made my body wrench with anger towards him, and I felt joy when I read about the health of her newborn son. I felt worried when she reported her poor health, and I was intrigued to learn of Henrietta’s support of Henry Clay’s Whig party. Henrietta has become more than a passing acquaintance; she has become a close friend, albeit nearly two centuries later.

Kate McKee ’22

Student Curatorial Assistant, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

and

Frank Goodyear

Co-Director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art