A Hope Guy: R. Luke DuBois’s "32 Questions for DeRay McKesson"

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

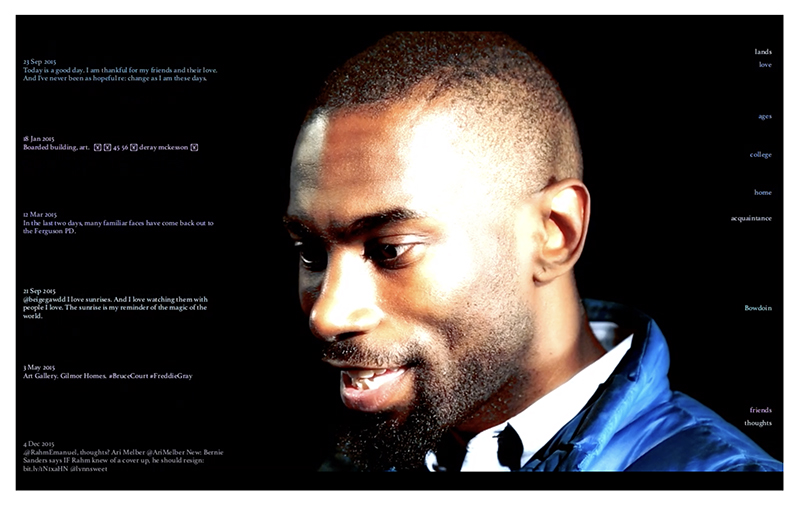

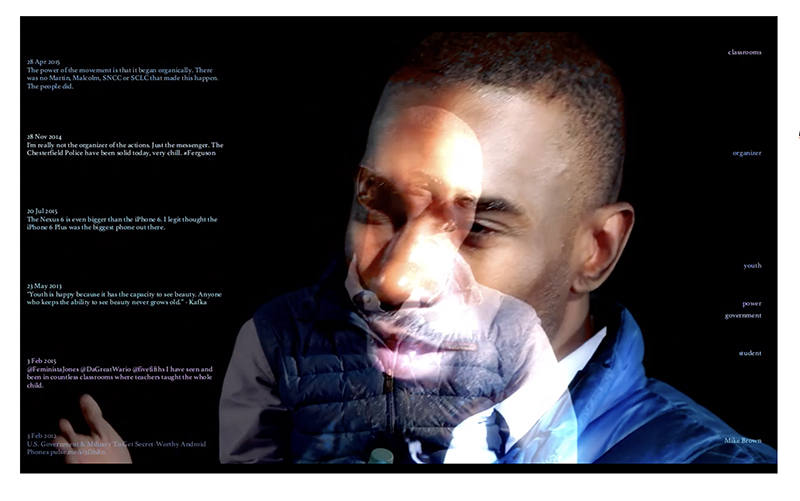

32 Questions for DeRay Mckesson, created for the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2016, generative digital media work on computer, with custom software, by R. Luke DuBois. Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund.

In March 2016, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art unveiled 32 Questions for DeRay Mckesson, a work of time-based media art created by R. Luke DuBois in 2016 in tandem with the exhibition R. Luke DuBois—Now (March 31 until September 4, 2016). Provocative and engaging at the time, the portrait’s power has only continued to grow, especially in tandem with the ongoing work of its subject, DeRay Mckesson, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, who will receive an honorary doctorate from his alma mater in May.

As suggested by the title of the work, the portrait takes the form of a conversation with Mckesson based upon questions. Determined to ensure the work was firmly rooted within the culture of the College that had nurtured Mckesson’s own intellectual development, DuBois worked with the Museum to consult with student leaders about the project. In response, Ashley Bomboka, ’16, President, Bowdoin African American Society, and Daniel Mejia-Cruz ‘16, President, Bowdoin Student Government, who had themselves publicly interviewed Mckesson at Bowdoin in September 2015, generously reached out to fellow students and collected suggested questions from them representing each of the classes then in residence at Bowdoin.

In 32 Questions for DeRay Mckesson, the activist describes his alma mater as the place where he “fell in love with [his] mind” and credits his work in student government with helping him to develop critical skills on which he would come to rely as an activist. The innovative structure of the portrait reflects Mckesson’s own forward-thinking and strategic use of new social media to frame, communicate, and inspire support for the campaign to end systemic racism and police violence. As he noted in the September 2015 presentation he made at Bowdoin: “I fundamentally believe that the digital space has allowed us to think about what it means to organize to create relationships that we can leverage to be power in new and fundamental ways. … What does that mean? How do we continue to explore these new frontiers of what this social media space has allowed us to do? I have a large reach with Twitter—[today he reaches over 1 million followers] … How do we use that to bring people together in new and powerful ways? That’s a question that we are still exploring.” Mckesson offered this insight as part of his reflection on a new way of organizing. Indeed, part of Mckesson’s influence is no doubt due to his ability to operate at the intersection of many disciplines: politics, education, activism, and organizing. Indeed, we might describe his successful career as quintessentially hybrid.

In 32 Questions for DeRay Mckesson, the activist describes his alma mater as the place where he “fell in love with [his] mind” and credits his work in student government with helping him to develop critical skills on which he would come to rely as an activist. The innovative structure of the portrait reflects Mckesson’s own forward-thinking and strategic use of new social media to frame, communicate, and inspire support for the campaign to end systemic racism and police violence. As he noted in the September 2015 presentation he made at Bowdoin: “I fundamentally believe that the digital space has allowed us to think about what it means to organize to create relationships that we can leverage to be power in new and fundamental ways. … What does that mean? How do we continue to explore these new frontiers of what this social media space has allowed us to do? I have a large reach with Twitter—[today he reaches over 1 million followers] … How do we use that to bring people together in new and powerful ways? That’s a question that we are still exploring.” Mckesson offered this insight as part of his reflection on a new way of organizing. Indeed, part of Mckesson’s influence is no doubt due to his ability to operate at the intersection of many disciplines: politics, education, activism, and organizing. Indeed, we might describe his successful career as quintessentially hybrid.

The same might be said of the artist R. Luke DuBois. Like many contemporary visual artists, DuBois’ work resists easy categorization, encompassing filmmaking, printmaking, collaborative performance, computer programming, and data mining. But, perhaps somewhat unusual among visual artists, DuBois teaches engineering at NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering, where he directs the Brooklyn Experimental Media Center. Keenly aware of our relationship to the numerous data streams that surround us, DuBois considers how we make sense of it, and how, in the process, we make sense of ourselves. He muses about his work: “What I am ultimately trying to do is bring the data back down to where it belongs, which is language, which is human, which is connection.”

DuBois’s attention to the importance of connection echoes that of Mckesson himself. And, appropriately, this commitment is mirrored in the way in which the portrait is constructed. Building upon the format of the interview, each of the thirty-two questions is silently projected on the screen. The portrait captures Mckesson’s thoughtful replies to each query. But, as Mckesson speaks, the viewer notices something atypical of traditional documentary formats. On the right appear tags developed by the artist after digitally segmenting the interview. The tags provide an index of subjects discussed by Mckesson and, through custom software written by DuBois, prompt the scroll of tweets on related topics at the left, connecting his self-reflective comments with issues addressed in real time by his Twitter feed.

The portrait, then, not only captures Mckesson visually in his signature blue Patagonia vest, and shares his words, allowing him to reveal something about his background and personal and political commitments, it also reflects the link between words and actions in real-time by interconnecting the interview with the activist’s own tool for connecting with followers. Perhaps most significantly, the portrait is generative, which is to say that the portrait does not form a repetitive loop, but instead, when installed, continues to link to new tweets by Mckesson. The portrait, then, will continue to take on new “life,” as it were, as long as Mckesson continues to tweet, revealing new connections between his current activities and advocacy and the words he used to describe himself in 2016.

Perhaps most important, 32 Questions for DeRay Mckesson creates a framework for capturing, sharing, and reflecting upon Mckesson’s goals and the insights that motivate his work. “People tend to lose hope … what do you say to those people,” reads one of the final questions in the interview. Mckesson’s reply not only reflects upon the source of his own resilience, but offers enduring encouragement that testifies to the influential impact of his vision: “I think of hope as the belief that our tomorrows can be better than our todays … I just won’t accept that this is the best it can be. I just won’t accept that. … I’ve seen people fall in love with their minds, those same minds that they didn’t think were worth anything. So I’m a hope guy, because I’ve seen its power.”

Anne Collins Goodyear

Co-Director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Illustration: 32 Questions for DeRay Mckesson, created for the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 2016, generative digital media work on computer, with custom software, by R. Luke DuBois. Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund.