Recent Acquisitions: The Art of Chuzo Tamotzu

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Still Life with Newspaper, 1931, oil on canvas, by Chuzo Tamotzu. Gift of Helena L. Katz, MD, in honor of her aunt and uncle, Louise and Chuzo Tamotzu

In 2021, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art welcomed a remarkable donation of seventeen works created by Chuzo Tamotzu (1888–1975), thanks to the generosity of Helena Katz, a niece of the artist. As readers of the E-Bulletin will recall, the Museum had an opportunity to exhibit a small selection of works by Tamotzu in 2017 in conjunction with Perspectives from Postwar Hiroshima: Chuzo Tamotzu, Children’s Drawings, and the Art of Resolution (January 10–April 16, 2017). The exhibition focused on an exchange that he organized in 1953 of children’s drawings made in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where Tamotzu lived, and Hiroshima, Japan, the country of his birth. An online version of the show is now available.

Cognizant of the importance of nurturing and encouraging the young in developing ties between Japan and the United States, Tamotzu was a highly accomplished artist in his own right. This gift provides an exciting opportunity to reexamine his legacy and his many contributions to American modernism.

Born in Japan in 1888, Tamotzu arrived in 1920 in New York, where he became a vital part of modernist circles. Settling in Greenwich Village, Tamotzu built friendships with artists such as Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Hideo Benjamin Noda, Philip Evergood, and John Sloan. Tamotzu’s style, which he would later describe as “expressionistic realism,” reflected an interest in contemporary urban life as well as a concern for social justice. Even his seemingly traditional genre paintings reflected his sense of social responsibility—and his sly sense of humor. His 1931 Still Life with Newspaper, for example, featured assorted items lying upon the Daily Worker, playfully alluding to his affiliation with the John Reed Club and the American Communist Party. The artist, who wished to alleviate the suffering of vulnerable communities, was supportive of a political philosophy that he believed could improve working and living conditions for the poor.

Espousing convictions common among artists of the era, Tamotzu did not consider his politics incompatible with the promise of American democracy. In 1931 he co-founded An American Group to create opportunities for “younger, less well known artists,” and in 1935 he was invited to serve on the Federal Art Project. His involvement, however, was cut short in 1937 by a change in policy which denied positions to non-citizens. This created an unresolvable dilemma, for although the artist had resided in the United States for over a decade and a half, his Japanese heritage made him ineligible for naturalization.

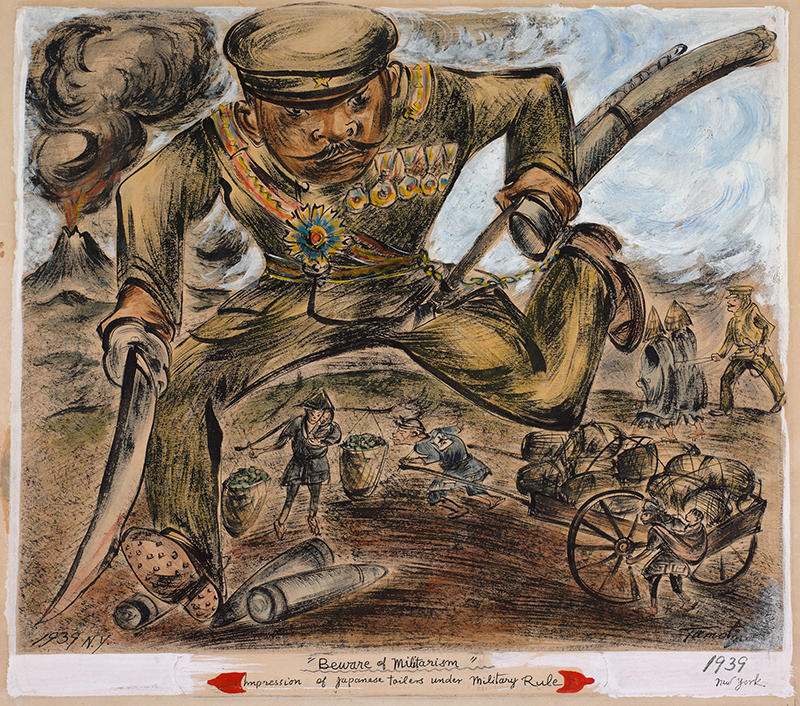

Despite such discrimination, Tamotzu continued to position himself enthusiastically as an American artist. His 1939 painting, Beware of Militarism was done, as he later told a journalist, not only as a protest against the bellicose policies of the Japanese government, but, even more importantly, “to prove that not all Japanese wanted war.” When war did come, Tamotzu immediately proclaimed his allegiance to the United States, joining other members of the “Committee of Japanese Artists Resident in New York City,” to sign a public declaration on December 12, 1941 condemning Japanese aggression. Fulfilling his pledge to support the United States, Tamotzu volunteered with the Army’s Office of Strategic Service, serving both in the United States and abroad. Yet despite this service, the artist found himself the target of politically motivated persecution following World War II. In 1948, Tamotzu left New York with his new bride Louise Kates and settled in Santa Fe, where his friend and mentor John Sloan provided the artist with the use of his home and studio. Tamotzu would remain there for the duration of his career.

Despite such discrimination, Tamotzu continued to position himself enthusiastically as an American artist. His 1939 painting, Beware of Militarism was done, as he later told a journalist, not only as a protest against the bellicose policies of the Japanese government, but, even more importantly, “to prove that not all Japanese wanted war.” When war did come, Tamotzu immediately proclaimed his allegiance to the United States, joining other members of the “Committee of Japanese Artists Resident in New York City,” to sign a public declaration on December 12, 1941 condemning Japanese aggression. Fulfilling his pledge to support the United States, Tamotzu volunteered with the Army’s Office of Strategic Service, serving both in the United States and abroad. Yet despite this service, the artist found himself the target of politically motivated persecution following World War II. In 1948, Tamotzu left New York with his new bride Louise Kates and settled in Santa Fe, where his friend and mentor John Sloan provided the artist with the use of his home and studio. Tamotzu would remain there for the duration of his career.

Anguished by the destructive conclusion of World War II, Chuzo, as noted earlier, worked to build bridges between the US and Japan. This included the aforementioned children’s art exchange, which received national attention. It also extended to the creation of paintings that critiqued warfare, such as Helena’s Imaginary Air Shelter (1955). The painting features Tamotzu’s niece, Helena Katz, hiding in what appears to be a trench hastily constructed in a garden, a shovel still visible. Observing her upturned face and expectant expression, the viewer of the painting cannot help but wonder what has captured the girl’s attention. Just what lies outside the frame, whether real or imaginary, that has prompted her protective embrace of a doll in Japanese dress and caused her to drop her ribboned hat and book? Leaving open these questions, Tamotzu prompts his audience to consider the nature of childhood aspirations and concerns: just what responsibility do we have to protect the young and the world they will inherit? Concerned above all with the cause of peace, Tamotzu would continue to work until his death in 1975.

Anguished by the destructive conclusion of World War II, Chuzo, as noted earlier, worked to build bridges between the US and Japan. This included the aforementioned children’s art exchange, which received national attention. It also extended to the creation of paintings that critiqued warfare, such as Helena’s Imaginary Air Shelter (1955). The painting features Tamotzu’s niece, Helena Katz, hiding in what appears to be a trench hastily constructed in a garden, a shovel still visible. Observing her upturned face and expectant expression, the viewer of the painting cannot help but wonder what has captured the girl’s attention. Just what lies outside the frame, whether real or imaginary, that has prompted her protective embrace of a doll in Japanese dress and caused her to drop her ribboned hat and book? Leaving open these questions, Tamotzu prompts his audience to consider the nature of childhood aspirations and concerns: just what responsibility do we have to protect the young and the world they will inherit? Concerned above all with the cause of peace, Tamotzu would continue to work until his death in 1975.

Anne Collins Goodyear

Co-Director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Illustrations:

Beware of Militarism, 1939, Sumi brush, watercolor, and pen, by Chuzo Tamotzu. Gift of Helena L. Katz, MD, in honor of her aunt and uncle, Louise and Chuzo Tamotzu

Helena’s Imaginary Air Shelter, 1955, oil on canvas, by Chuzo Tamotzu. Gift of Helena L. Katz, MD, in honor of her aunt and uncle, Louise and Chuzo Tamotzu