Object of the Month: Cameron Keith Gainer’s "Forest Through the the Trees"

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

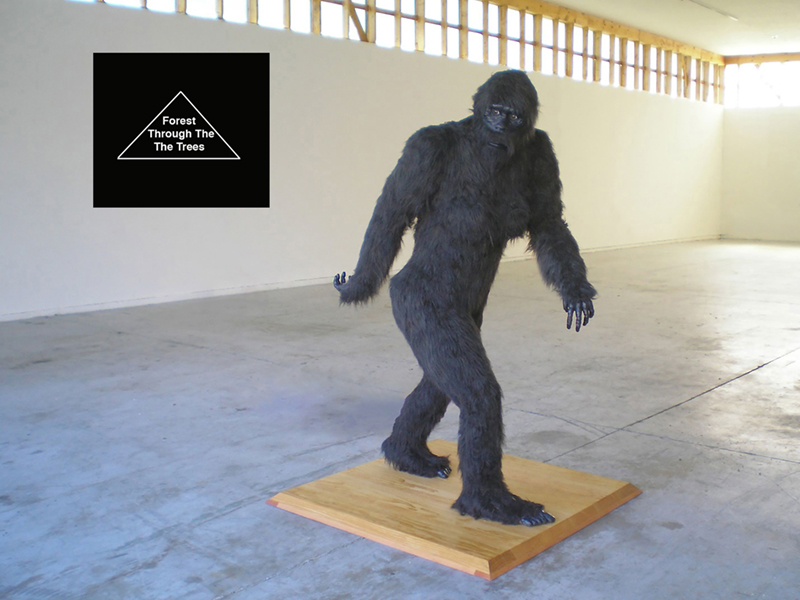

Forest Through the the Trees, 2008, steel, fiberglass, faux fur, modeling compound, glass eyes, by Cameron Gainer. 75 x 48 x 32 in. (190.5 x 121.92 x 81.28 cm) Archival Collection of Marion Boulton Stroud and Acadia Summer Arts Program, Mt. Desert Island. Gift from the Marion Boulton “Kippy” Stroud Foundation. Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

What do you notice first about Cameron Keith Gainer’s startling artwork? Is it the bold striding gorilla? Or is it the title, formatted in its pyramid arrangement?1 Is the triangle intended to reinforce the notion of “treeness” in a fashion akin to a conifer? Do we discern a tree from the forest? Or is something else going on? Just what is the title of this work? Look again. It is easy to miss the second “the” in the work’s title. The Bouma shape of the triangle affects the brain’s ability to immediately recognize the word’s repetition. As the psychologist Alan Castel puts it: “Sometimes we only know how our mind works by noticing when it fails.”2 Gainer’s work playfully challenges the viewer to consider the relationship between what we see and what we know, to discern illusion from reality and to question our ability to do so at all.

Gainer’s Forest Through the the Trees represents a life-size rendition of Bigfoot appropriated from the well-known Patterson-Gimlin Film of that title in 1967. His sculpture captures the creature in iconic fashion: mid-stride and looking at the camera. Carefully mimicking the famous frame 352 of the film, the sculpture is covered in lifelike brown-black faux fur and has a pair of piercing glass eyes. The work was originally shown at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, New York in 2006 as a part of the exhibition “EAF06: 2006 Emerging Artist Fellowship Exhibition.” It is one of three public commissions by Gainer that explore the theme of myth and urban legend. The other two works include the 2008 _[ (a glyph, which is the proper title of a work), also known as “Minne the Lake Creature,” that represents the Loch Ness monster based on a famous 1934 photograph, most recently exhibited by the Minneapolis Parks Foundation; and the 2008 Impact Sight, depicting the effect of a meteor strike against the University of South Florida Museum in Tampa.

Forest Through the the Trees plays with our perceptions of photography, documentation, and reality. The work was made during the U.S. war in Iraq and offers a serious reflection on photography and its use for manipulating public perception. While photography is often relied upon by the public as credible witness of reality, it can be easily staged. When a photo is widely circulated and recognized among the public, it may come to take on the status of “truth,” even if the image has been doctored to manipulate its representation of specific events. Through such a mechanism, fiction may become fact. Among Gainer’s inspirations for this work is Robert Capa’s war photography, including his well-known image The Falling Soldier, the authenticity of which has been widely questioned. Another inspiration for Gainer is Colin Powell’s 2003 United Nations speech, which relied upon faulty intelligence—including the misinterpretation of surveillance photography—which was later discredited, to justify the American invasion of Iraq.3 Taking the question of how the public “reads” images a step further, Gainer played with the deceptiveness of strategies for representing “truth” during the work’s installation at Socrates Sculpture Park, when the public sculpture became a “photo-op,” allowing viewers to pose with the work and perpetuate the “hoax” on social media.4

As noted at the outset of this reflection, the work’s title echoes concerns about representation and perception. The title “Forest Through the the Trees” brings to mind the problem of “seeing the forest for the trees,” a phrase used to describe people who focus too much on the details of a problem and miss the big picture. If puns are indeed connected with the work, might Gainer also be hinting at “the 800-pound gorilla” we often try to suppress in ignoring inconvenient realities? Sometimes, as the sculptor notes, such “gorillas” may even take the form of public sculpture, which can reinforce political repression in full sight. In recent years, around the world, members of the public have begun to demand the removal of such works.5

Forest Through the the Trees has uncanny resonance with our own reliance on social and news media, which seem to have an increasingly tenuous relationship to the “real.” Just how is information being presented, and what are some of the “tricks” that might instantaneously transform it into something else in our minds? Today, in an era where virtually everyone absorbs news from some combination of mass media and social media, the risk of “cognitive blindness”—which leads us to discard intellectually what we are not prepared to “see” or to understand—deserves our full attention.6 As we attempt to search for truth today, especially in the midst of a global pandemic, the risk of misrepresentation and misperception is rife. How can we train ourselves to discern facts from illusions? The need to do so has never seemed more urgent.

Gainer’s sculpture is part of the BCMA’s Archival Collection of Marion Boulton Stroud and the Acadia Summer Arts Program, Mt. Desert Island, Maine, donated in 2018 by the Marion Boulton “Kippy” Stroud Foundation. Gainer describes himself as a conceptual artist, stating that “the gesture of the idea can be manifested in many forms.” In addition to his work as a visual artist, Gainer is also the publisher and editor of The Third Rail, a quarterly journal on addressing art, politics, philosophy, and culture.

Notes

1 Cameron Keith Gainer’s attention to titles is also evident in his _[ [a glyph], the proper title of a work, also known as “Minne the Lake Creature,” which plays off a 1934 photograph said to picture the Loch Ness monster, see “Minne,” Minneapolis Parks Foundation at: https://mplsparksfoundation.org/projects/minne/. We thank Cameron Keith Gainer for this information and for his generous response to our interest in this work. His insights have been invaluable.

2 Alan Castel, “Why we Stop Noticing the World Around Us,” Psychology Today, June 26, 2018; https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/metacognition-and-the-mind/201806/why-we-stop-noticing-the-world-around-us, last referenced May 18, 2020. We thank Cameron Gainer for bringing this article to my attention.

3 “Cameron Gainer,” Socrates Sculpture Park, https://socratessculpturepark.org/artist/cameron-gainer/

4 “Forest Through The The Trees at The Fabric Workshop and Museum,” Art Daily, January 2008; https://artdaily.cc/news/23052/Forest-Through-The-The-Trees-at-The-Fabric-Workshop-and-Museum#.Xqy-ThNKg_M (accessed May 25, 2020)

5 See, for example, Tyler Stiem, “Statue Wars: What Should We Do with Troublesome Monuments,” The Guardian, September 26, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/sep/26/statue-wars-what-should-we-do-with-troublesome-monuments; accessed May 18, 2020. We thank Cameron Keith Gainer for sharing this article.

6 See, for example, Institute for the Future, “Building a Healthy Cognitive Immunity: Defending Democracy in the Disinformation Age,” released Jan. 10, 2020. We thank Cameron Keith Gainer for bringing this to our attention.

Yvonne Fang, Bowdoin Class of 2020

and

Anne Collins Goodyear

Co-Director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art