A Fascinating "Fountain" and "The Blind Man" (nos. 1 and 2) Enter the BCMA Collection

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

On or about Friday, April 6, 1917, one Richard Mutt submitted Fountain to the Grand Central Palace in New York, to take its place in the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, scheduled to debut four days later. Having paid six dollars to cover the cost both of membership in the society and his entry fee, the artist had every right to expect that his artwork would find its way into the installation. Pledging “no jury” and “no prizes,” the newly formed Society, which had gained over 600 members within two weeks of its launch in early 1917, had promised to install all works alphabetically, by the name of the artist. But what ensued, instead, was an uproar, witnessed and reported on by the young artist Beatrice Wood. This contest pitted the infuriated artist George Bellows, who claimed the work was “indecent,” against the cool-headed patron Walter Arensberg who studiously upheld the bylaws of the Independents, insisting that, “if [it] is an artist’s expression of beauty, we can do nothing but accept his choice.”

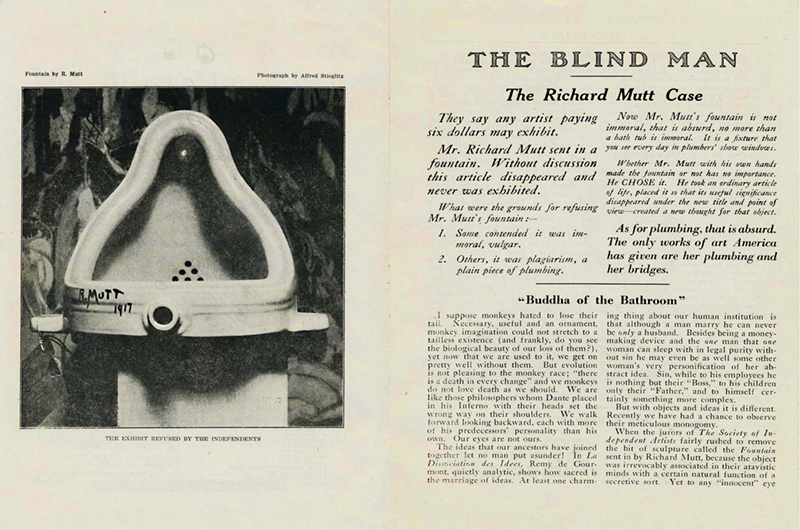

The scandalous reception reflected the shocking nature of the piece: Fountain consisted of a men’s urinal, rotated 90 degrees onto its back. The unconventional positioning of the implement was confirmed by the artist’s signature, boldly affixed to the object, which had been manufactured by Mott Iron Works, a well-known manufacturer of bathroom fixtures. In the ensuing debate, playing out until virtually the opening moment of the exhibition, a majority of the directors of the Society of Independent artists voted to exclude the work, with the Board’s majority going on record to assert that Fountain was “by no definition, a work of art.”

The debate, and, most likely, its outcome, had been anticipated by the artist behind the pseudonym of Richard Mutt: Marcel Duchamp. As the recent émigré from France recognized, in its very rejection of Fountain, the Society’s Board of Directors pointed to the central question raised by the object: just what is a work of art? That powerful query is what has vaulted the work into the canon of art history, raising it well above the level of a mere provocation. The Bowdoin College Museum of Art is proud to have recently added to its collection both numbers of the famous publication, The Blind Man, co-edited by Marcel Duchamp, Henri-Pierre Roché, and Beatrice Wood, that transformed this “piece of plumbing,” created in the spirit of Dada’s disruption of the conventions of western art and culture, into one of the most important works in the history of art.

The decision to reject Mutt’s submission led to the prompt resignation of Marcel Duchamp and Walter Arensberg from the Board of the Society of Independent Artists, and Fountain was soon transported to Alfred Stieglitz’s famous 291 Gallery. For a short period, Stieglitz put it on view, the only public exhibition of the 1917 object. (It was subsequently discarded and later recreated, most famously in a 1964 edition by Duchamp and Arturo Schwarz.) While installed at 291, Fountain was photographed by Stieglitz in collaboration with Duchamp, producing an image that would come to serve as the object’s official pictorial documentation.

The photograph, of which the original too has disappeared, was published in The Blind Man, no. 2, together with an editorial and related articles that provided a scathing response to censorship imposed by the Society in barring Fountain from the exhibition. This turn of events suggests that Duchamp and his collaborators understood that the publication itself had a critical role to play in documenting and disseminating new ways of understanding the very nature of art in the early twentieth century. While each of the articles published in The Blind Man, no. 2, is important in its own right, perhaps none has proved more influential than the unsigned editorial, “The Richard Mutt Case,” published opposite Stieglitz’s photograph, and anonymously penned by Duchamp, Roché, and Wood. The article concludes with an assertion that has proved foundational to subsequent generations of modern and contemporary artists, paving the way for overtly conceptual approaches to art-making. The three editors emphasized: “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.”

Fountain has come to be seen as one of the most important works of art of the twentieth century, voted by art experts in 2004 as “the world’s most influential work of modern art,” as Charlotte Higgins reported for The Guardian.

In its pioneering articulation of principles that are still deeply relevant to art-making today, then, and particularly in its coverage of both the lead up and response to the submission of Fountain, The Blind Man has thus become a document essential to the history of modern and contemporary art. The deliberate disposal of the object itself by its makers and its relegation to the pages of The Blind Man further points up the special status of this journal as an art work in itself, representing through its pages the inaugural example of conceptual art, a movement that has now become ubiquitous.

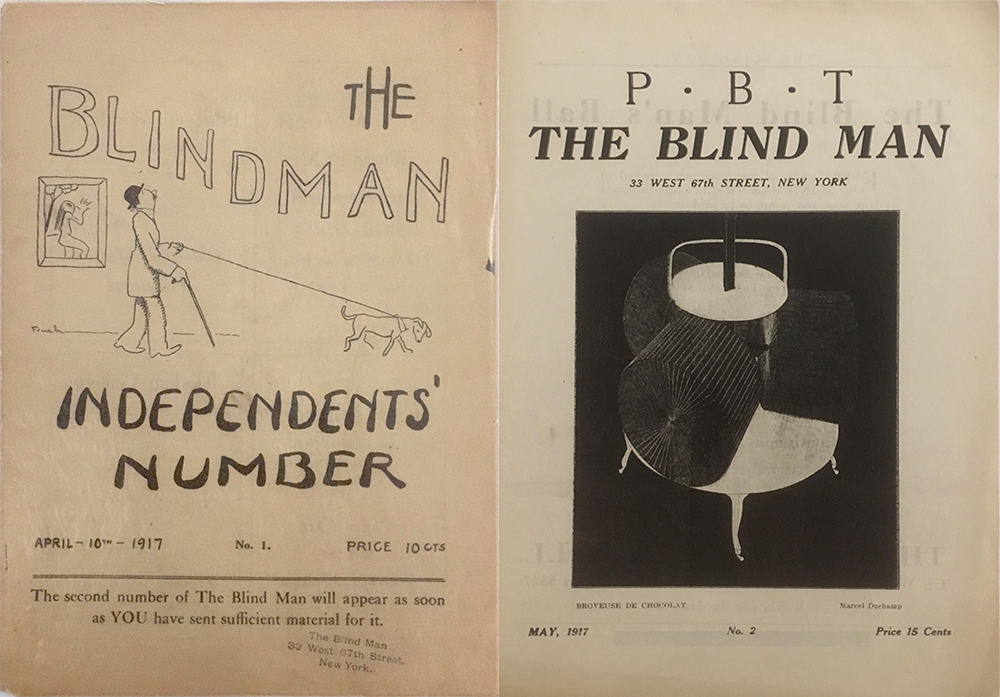

In many ways, the establishment of the short-lived journal The Blind Man, launched in 1917 after the establishment of the Society of Independent Artists, was as important a contribution to the history of modern and contemporary art as Fountain, which it documented. The Blind Man featured images and text of celebrated modern artists, providing a platform for artists to speak about critical issues in modern art, especially the Dada art movement. While The Blind Man was a short-lived magazine that published only two issues (no. 1 in April and no. 2 in May), it made a significant contribution to ongoing debates on modern art. The Blind Man, no. 1, includes written contributions from Roché, Wood, and Mina Loy that address the foundation of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, based upon the model of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in France, and the importance of its spring 1917 exhibition, open to all members of the society paying the entry fee. Roché’s opening essay also outlines the editorial aims for The Blind Man, stating, “The Blind Man will be the link between the pictures and the public—and even between the painters themselves.”

The Bowdoin College Museum of Art acquired its full set of The Blind Man from a private collector. Issue number 1 of this set has a notable provenance, and the Museum is only its fourth owner: it was originally owned by Henri-Pierre Roché, The Blind Man’s co-editor, and then by the scholar Michel Sanouillet, who published the first collection of Duchamp’s writings, before being privately held. We look forward to sharing both volumes of this important publication with artists and historians and hope that they will take inspiration from the pioneering publication, as they in turn consider art’s important role in transforming the way in which we see the world.

The covers of The Blind Man, Nos. 1 & 2, (1917), Marcel Duchamp, Henri-Pierre Roché, and Beatrice Wood (publishers)

The Museum is grateful for support for this acquisition provided by our colleagues in George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, and for funding made possible by these BCMA endowments: Barbara Cooney Porter Fund, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund, and The Philip Conway Beam Endowment Fund; as well as from The Stones-Pickard Special Editions Book Fund, George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library.

Anne Collins Goodyear

Co-Director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

I thank Allison Martino, formerly Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at the BCMA and now Laura and Raymond Wielgus Curator of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Art of the Americas at the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University, for her valuable contributions to research on The Blind Man, nos. 1 and 2.