A Tribute to Dr. David C. Driskell H’89

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

(Left to right) Rodney Moore, Dr. Driskell’s nephew; David C. Driskell H’89; Alvin Hall ’74; and Julie McGee ’82, on November 9, 2019.

A celebrated visual artist, a leading historian in the field of African American art, and a dedicated educator, Dr. David C. Driskell H’89 left an important mark with every institution and individual with whom he was connected, including here at Bowdoin and the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Having first come to Maine as a student at the Skowhegan School of Art and Design in 1953, Driskell established a permanent foothold in the state in 1961 when he purchased a property in Falmouth, where he would establish a home and studio. In the spring semester of 1973, while on sabbatical leave from Fisk University, Driskell taught art and art history at Bowdoin, becoming one of the first teachers in the Department of Africana Studies. Among his students were Geoffrey Canada ’74, Ken Chenault ’73, and Alvin Hall ’74. Driskell’s passionate commitment to education was evident in a 2018 interview with Miles Brautigam ’19 and Anne Collins Goodyear: “I always wanted to be a teacher,” he explained. “That’s my ministry.” Driskell’s important contributions to the early history of Africana Studies at Bowdoin formed the basis of his conversation with Julie L. McGee ’82 last fall during the 50th anniversary celebration of the foundation of Africana Studies, the African American Society, and the John Brown Russworm African American Center. In connection with that event, the Museum of Art hosted a pop-up exhibition, The Art of David C. Driskell, H’89 and the Art that Inspires Him.

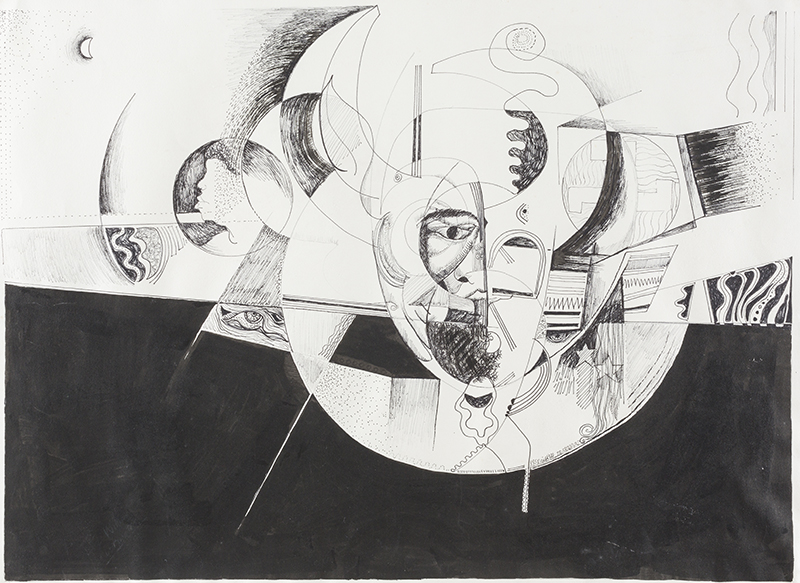

Shortly before Driskell arrived to teach at Bowdoin, he created Masking Myself, a 1972 self-portrait acquired by the Museum last spring. The complex imagery of the work reflects the artist’s interest in the western idiom of Cubism, as well as that of African art, itself an inspiration for the emergence of Cubism. Indeed, the artist had made his first trip to Africa in 1969, returning in 1970 and in 1972, when he undertook a multi-nation lecture tour about African American art under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. Driskell’s interest in the multifaceted nature of identity finds reflection in this self-portrait drawing that is explicitly concerned with masking, a theme explored extensively in historic and contemporary African American literature by such authors as W. E. B. DuBois, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Maya Angelou, and Toni Morrison. How an artist presents oneself to the world and the attendant questions Driskell poses regarding his own relationship to society reveal an awareness of personal vulnerability emblematic of tremendous courage. In the fall of 1973, the Museum of Art hosted one of the first solo exhibitions of his work. Driskell noted in the accompanying catalogue: “There are times when I would like to set the whole world right by making images that speak out my convictions. In recent years, I have turned my attention to images that reflect the exciting expression that is based in the iconography of African art. In so doing, I am not attempting to create African art. Instead, I am interested in keeping alive some of the potent symbols that have significant meaning for me as a person of African descent.”

Born in Georgia, the son of a father who served as a Baptist (initially African Methodist Episcopal) minister and a mother who was deeply knowledgeable about the medicinal properties of herbs and other flora, Driskell’s father introduced him to the Scriptures and the foundations of Western philosophy, while his mother acquainted him with the natural world, inculcating a love for forests and gardens. Driskell’s strong commitment to using art to explore and share aspects of his personal history and his interest in the link between cultures became important aspects of his work.This is reflected in works by him that the Museum of Art has collected, including Let the Church Roll On (1995–96) and Shaker Chair and Quilt (1988).

Driskell’s contributions to American art and letters have been recognized by thirteen honorary degrees, including one from Bowdoin in 1989. As a testament to his pioneering achievements, the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the African Diaspora was founded in 1989 at the University of Maryland, and in 2000 President Bill Clinton awarded him the National Humanities Medal. Driskell was elected in 2018 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, of which James Bowdoin II was a founder and the first president. These honors provide some indication of Driskell’s generosity with his numerous intellectual, organizational, and creative gifts during his lifetime. Of equal importance is the powerful legacy he leaves behind. As he observed late in his career: “The most important thing I think is our creative spirit. Our love for one another. And how we see above and beyond all of the barriers that we put up like race, or gender. All these things that separate us. Art is that one universal language that helps to clear up and seems to give us hope if we only listen, believe, and move forward in that sense of spirit.”

Masking Myself, 1972, ink and marker, by David Driskell. Museum Purchase, Barbara Cooney Porter Fund, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

A Remembrance of Dr. David C. Driskell appeared in the Bowdoin Orient on April 10, 2020.

Watch “Africana Studies and the Visual Arts: A Conversation with David C. Driskell and Julie McGee” a “Fireside Chat” recorded on Saturday, November 9, 2019. The discussion was part of the AF/AM/50 weekend at Bowdoin College.

Unless otherwise noted, quotations from the artist come from an interview conducted by Anne Collins Goodyear, Co-Director, and Miles Brautigam ’19, on July 19, 2018.