"Emerging Modernisms" and "The Blind Man"

By Bowdoin College Museum of Art

With the opening of Emerging Modernisms: American and European Art, 1900-1950 (June 29, 2019 –January 5, 2020) comes an opportunity to explore the emergence of new artistic idioms during the first half of the twentieth century. This period was characterized in the West by the rapid transformative influence of new technologies such as wide-spread electrification, the telephone, X-ray, and industrialization. Artists developed ground-breaking modes of expression, including cubism and abstraction, and the photograph came into its own as a mode of aesthetic expression. Somewhat less celebrated has been the advent of publications about such experimentation. Alfred Stieglitz played a leading role as editor and publisher of Camera Work and was the inspiration behind the pioneering 291, co-published by Stieglitz, Marius de Zayas, Paul Haviland, and Agnes Meyer. Examples of each of these publications are now on view.

Inspired by these avant-garde journals, perhaps no other “little magazine” of the era had such long reach of The Blind Man, an experimental review launched in 1917 by Marcel Duchamp, Henri Pierre Roché, and Beatrice Wood. Thanks to a generous loan both issues of this short-lived publication will be included through early September.

In many ways, The Blind Man exemplified the spirit of “Dadaism.” The Dada movement, which roared into being in Europe and the United States immediately following the outbreak of World War I, boldly questioned the legitimacy of traditional political hierarchies by undermining traditional aesthetic categories of taste with seemingly “absurd” artistic gestures. While the association of a sightless individual with the title for visual arts magazine—a connection played up by the caricaturist Al Frueh in the drawing used on the first issue’s cover—was typically “Dada” in its seeming unsuitability, the title both raised the question of just who might be considered “blind,” as well as the privileged perception of a “second sight” that renders apparent truths obfuscated by the distractions of the physical world.

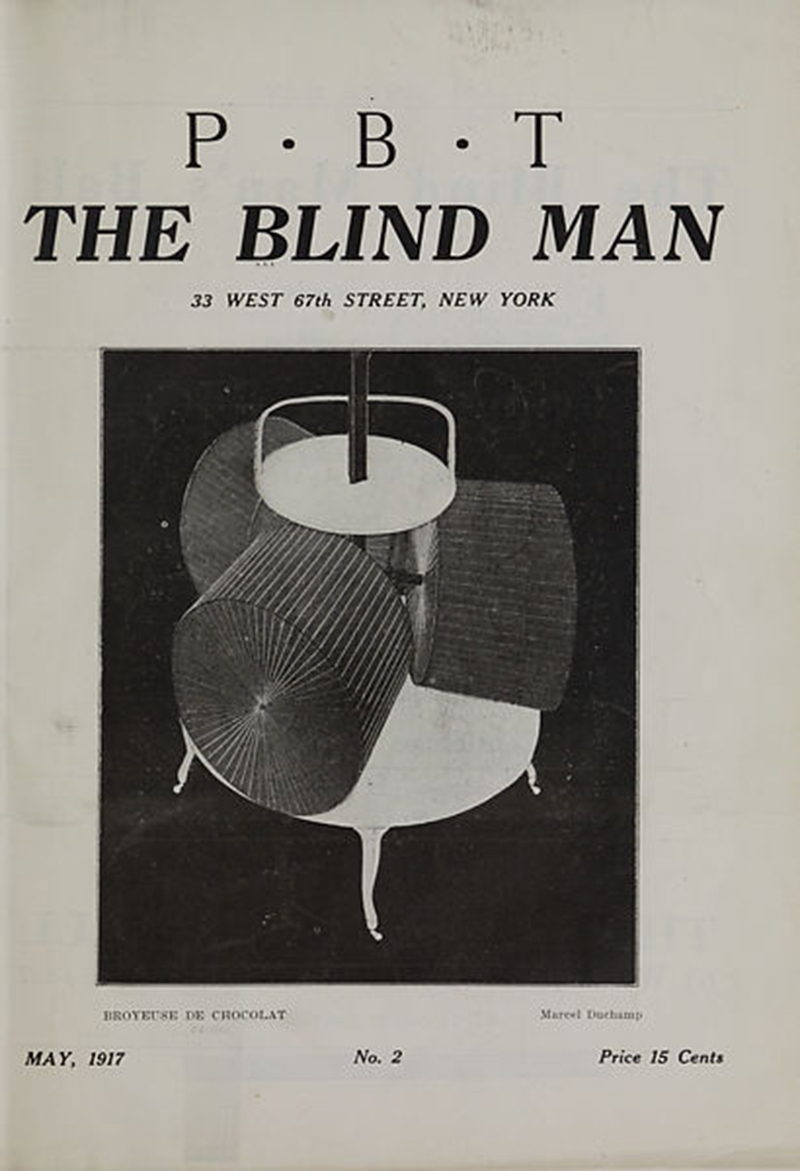

The Blind Man proved extremely important, disseminating both the voices and the artwork of international avant-garde artists active in New York. Its first volume appeared on the eve of the opening of the recently formed Society of Independent Artist’s inaugural, non-juried exhibition, with Henri Pierre Roché declaring in its opening article: “The Blind Man celebrates today the birth of the Independence of Art in America.” The organization emulated the French Société des artistes indépendants and sought to encourage the development of avant-garde art in the United States. The second issue—featuring Marcel Duchamp’s Chocolate Grinder (1914) on the cover—far from proclaiming the success of this endeavor, however, protested the exclusion from that exhibition of Duchamp’s revolutionary artwork, Fountain (1917), which had been submitted anonymously under the pseudonym of “R. Mutt.” In refusing to show the work, members of the Society, from which Duchamp immediately resigned, failed to honor the exhibition’s premise: that everything submitted with the appropriate entry fee would be shown.

Fountain, which represented one of Duchamp’s first “readymades,” a form of art relying upon the appropriation of a mass-produced object, publicly introduced Duchamp’s influential conviction that the idea behind the work was more important than the technical skill manifested in its creation, a principle now embraced by many contemporary artists. Indeed, to this end, the original urinal itself, later recreated and editioned, no longer exists. The photograph published by Stieglitz in The Blind Man, no. 2 represents its only official pictorial record. To create the infamous sculpture, Duchamp purchased a urinal and placed it on a pedestal on its back, and signed it with the pseudonym, “R. Mutt.” In response to the uproar the art work produced, and its resulting rejection from the 1917 Independents exhibition, the co-editors of The Blind Man—Duchamp, Roché and Wood—penned an accompanying article that detailed the artist’s intent (attributed at the time to Duchamp’s “alter ego,” Richard Mutt). “The Richard Mutt Case” emphatically declared: “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has not importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.”

With its combination of photographic documentation and artistic statement of intent, then, the second issue of The Blind Man represents, in itself, the inception of conceptual art. The revolutionary implications of Duchamp’s radical gesture have continued to reveal themselves in the century since the work appeared. In the 1960s, the artist became a guiding figure for many emerging artists eager to break free of the legacy of Abstract Expressionism, including Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Sturtevant. Many contemporary artists, including John Baldessari, Joseph Kosuth, Sherrie Levine, and Ai Weiwei, continue to demonstrate the strong echoes of Duchamp’s Fountain in art today.

Anne Collins Goodyear

Co-director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art