Uncovering Complicit Narratives

By Norell Sherman ’21

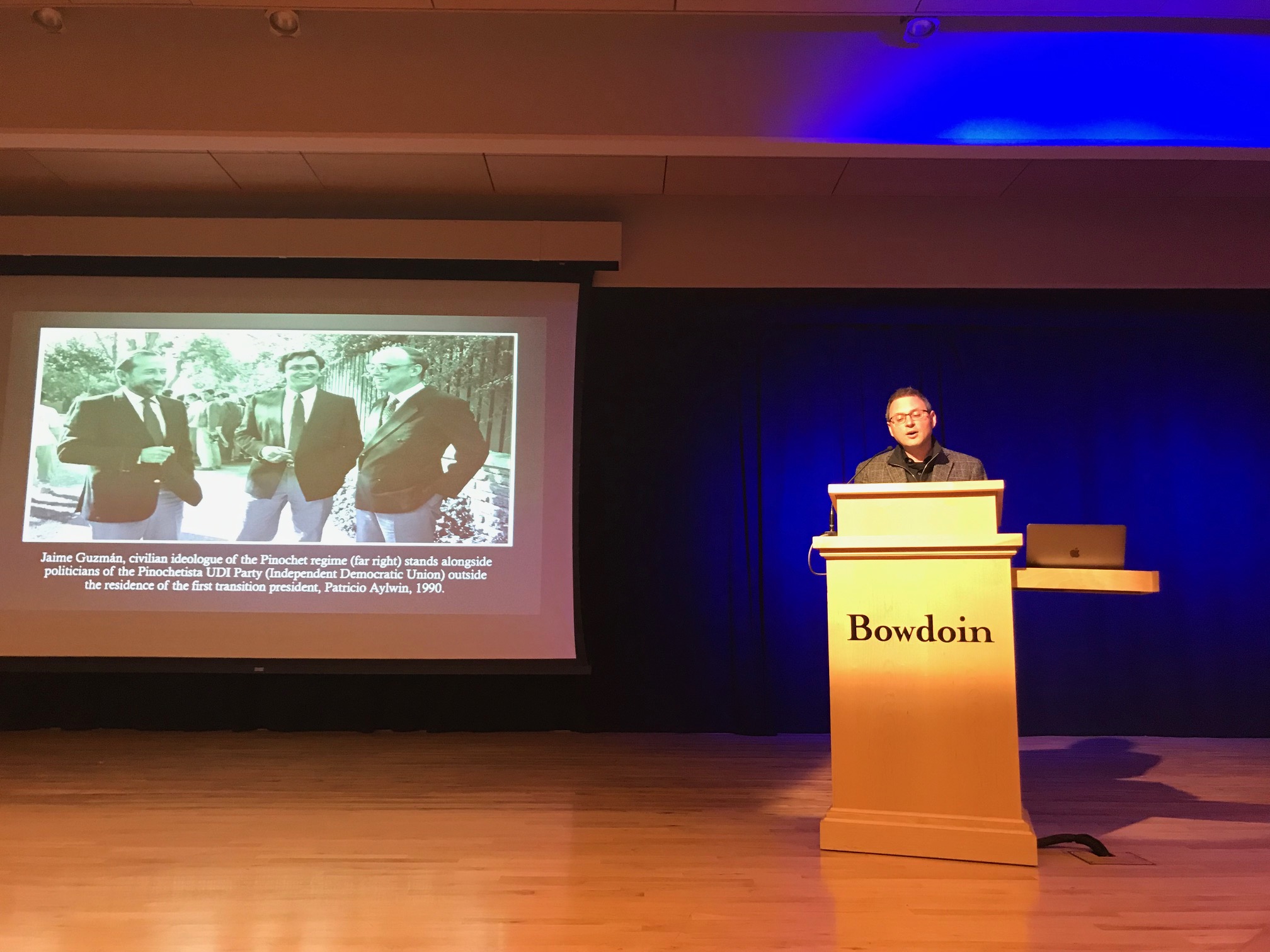

Guest speaker Michael Lazzara shares his presentation of the complicity of actors during the Truth, Memory, and Justice Colloquium.

While convicting those who committed atrocities and caused harm to others represents a path to the truth, often times, in the context of armed conflict, the public thinks mostly about military perpetrators as the targets of these prosecutions. Complicit citizens, however, often less visible, also perpetuate violence. As a speaker for the symposium put on by the Latin American Studies program “Memory, Truth and Justice: Lessons from the Peace Processes in South America,” Michael Lazzara, professor of Spanish and Human Rights at University of California Davis illuminated the importance of understanding the accomplice narrative for a heightened state of justice in post-dictatorial societies. In his presentation, “Memories of the General’s Butler: Civilian Complicity since Pinochet,” Lazzara concentrated on the role of civilian accomplices during the Pinochet regime in order to widen the scope of the conversation about violent actors during the dictatorship.

Declaring that civilian complicity is an area that has generally been ignored in official state memory, Lazzara explained that complicit actors were imperative to the consolidation and institutionalization of Pinochet’s repressive regime and reign of terror. Many accomplices however, have refused to take responsibility for their actions and several of these actors still maintain positions of power in roles such as government ministers and journalists.

To bring attention to the nuances of the complicit citizen experience and the representation of these actors by others, Lazzara seeks to highlight four multi-genre artistic and media interpretations—a documentary film, a novel and two public news interviews—of the same accomplice figure, Jorgelino Vergara, or the “Young Butler.” Under Pinochet, Jorgelino Vergara had been cast as a servant to the head of the secret police of Pinochet, he carried out atrocious tasks in many torture centers and he worked for intelligence agencies. In 2010, several interpretations of this figure entered the public sphere after Vergara had been wrongly accused of killing a communist leader and thus went to court to testify. For each popular representation of Vergara, Lazzara analyzes how the authors used rhetorical devices to frame the Young Butler, illuminating the ways in which representational mediums color the accomplice narrative.

Beginning with an analysis of the documentary El Mocito, directed by Marcela Said and Jean deCerteau, Lazzara illustrated how the directors sought to explore Vergara’s ambiguous characterization as both a victim and a victimizer, believing that he was a “victim of his circumstance”—of poverty and a lack of education. Lazzara highlighted cinematographic techniques that enabled the audience to empathize with Vergara ranging from the inclusion of interviews that portray Vergara as an involuntary actor and prisoner to the, to the manipulation of camera angles that create distance from and then closeness to Vergara in order to reflect his humanization. Yet, warning about the effects of enabling viewers to empathize with an accomplice, Lazzara dictates that spectators lose sight of the reality of accomplice’s agency and his active decisions to support the Pinochet regime.

Unlike the documentary, in La danza de los cuervos, author Fransisco Rebolledo rejects framing Vergara as a victim of his own circumstance and, instead, emphasizes his agency. By exposing the fact that Vergara had fantasized about joining the military and yearns for military power, Rebolledo demonstrates that Vergara actively made the decision to participate in the dictatorial state; he wasn’t an involuntary actor. At the end of the book, Rebolledo probes Vergara’s status as a victim and victimizer and ends the book with what Vergara “continues to hide.”

By analyzing interviews with Vergara for CNN Chile and on the show “Mentiras Verdaderas”, Lazzara illuminated the ways in which popular media sensationalizes testimony, as media outlets focus on upholding a performative quality. While the first interview privileged spectacle through interview questions that lacked substance, but evoked the shocking and jarring details of torture in the detention centers, the second interview demonstrated how popular media completely transformed Vergara’s public persona and enabled him to internalize the narrative that the media created for him: the interviewee introduces Vergara as “the man who changed the course of human rights in our country.” How could a civilian accomplice involved in so many of the violent atrocities under Pinochet adopt a label as a human rights hero?

In our course, “Attesting to Violence: Aesthetic of War and Peace in Contemporary Colombia”, in a conversation with author and professor Elvira Sanchez-Blake, we discussed the ways in which art cultivates empathy; this sense of understanding is crucial for being able to see conflict from varying angles. Especially in a context of war, people tend to write identities upon others based upon surface assumptions, instead of seeking to genuinely access another point of view. Yet, there are limits to this empathy, Lazzara demonstrated. “The post dictatorship period has had a tendency to produce a generalized notion of victimhood that can dangerously morph to encompass just about any subject position,” Lazzara said. “This is one key danger that lurks behind a vision of Jorgelino Vergara that deemphasizes his personal desires and ideological commitment to a violent counterrevolutionary state. It’s by contention that we must never forget about his agency. We must never forget that some people did the killing while other people were killed.”