On Remote Kent Island, Bowdoin Scientists Uncover Clues to Pollinator Intelligence

By Rebecca Goldfine

Assistant Professor of Biology Patricia Jones and five Bowdoin students recently published their findings on bee and wasp cognition in The Royal Society's Biology Letters.

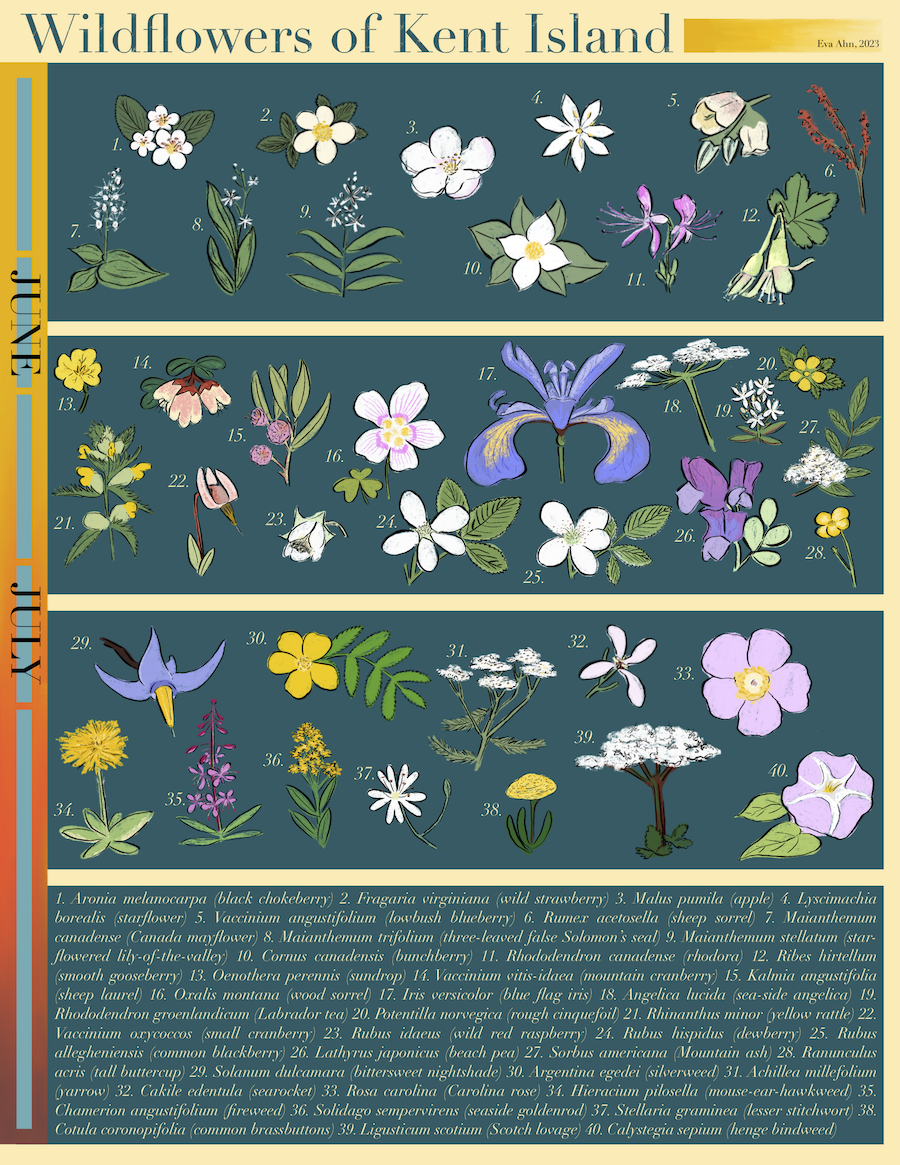

Their paper, "Pollinator cognition in a plant network" is based on research they conducted over three summers on the island. The students—Eric Diaz ’23, Neena Goldthwaite ’24, Hannah Scotch ’22, Sejal Prachand ’24, and Eva R. Ahn ’26—were supported by Kent Island summer fellowships.

The team first set out in 2019 to determine the ability of six pollinator species—four kinds of bees and two varieties of wasps—to learn plant colors and what effect this had on their nectar-seeking habits. All pollinating insects are “under similar pressures to forage efficiently in a mixed floral community,” the paper notes.

After conducting lab experiments on more than 200 pollinators and making more than 3,000 fieldwork observations, the researchers discovered that the more specialist pollinators that visit a select group of flowers are better at learning colors than the more generalist insects, which visit a broader range of flowers. Both behaviors are equally good but represent different foraging strategies.

In the paper, the researchers propose that being adept at color learning helps specialist insects forage more efficiently and be more selective, so they don't waste energy visiting the wrong flowers. “If [their preferred] plants are of distinct colors, this may...strengthen selection for color learning abilities,” they write.

In contrast, insects that aren’t as good at color learning stick to flowers with similar colors, reducing their need for advanced cognitive skills.

Building on this knowledge, scientists can continue to hone their understanding of what drives pollinator behavior. With insects in decline around the world, including the pollinators that ensure our food supply, studies like this one of plant-pollinator networks are critical. “Any dataset on which pollinators are visiting which plants is really useful for bee conservation work,” Jones said.

The special nature of Kent Island

The research team took advantage of Kent Island's unique site in the Bay of Fundy to undertake their study. “Islands are so useful for biology and ecology because of their isolation and containment,” Jones said.

Especially for pollinator research, she added. “The island provides us the opportunity to nail down the plant-pollinator network because we’re surrounded by cold ocean on all sides.”

“There is a knowable, manageable diversity here, so we can look at who are the insects and who are the plants with a level of confidence that is hard to do in mainland sites,” Jones said.

The island is also a productive place for students to learn fieldwork skills. Eva Ahn ’26, a coauthor of the pollinator paper and the artist who created its illustrations, said her summer on the island “opened my eyes to what research could be. Before it was a very mysterious thing.”

As an environmental studies and biology major, Ahn is interested in a career in ecology or marine biology. Her summer on Kent Island was special, she said, because she was able to spend lots of time outside and observe the natural world more closely. “It was a great opportunity to incorporate my interest in art into research, which helped me understand more deeply.”

What do bees know?

To gather data for their recently published study on color learning, the Kent Island researchers first had to discern how their pollinators perceive color. Bee and wasp vision, and their perception of color, differs greatly from humans.

Ahn said this aspect of the study was particularly important, both for the research and for conservation. “In the whole scheme of conservation and protecting these insect species, it's important to understand how they perceive the world. It's very different from us,” she said. “It's important to take into account their sensory perspectives when we’re trying to inform policies and methods of conserving these very important species that provide a lot of ecological benefits.”

To get a better sense of what the pollinators see, the team used Bowdoin's spectrometer to measure light wavelengths reflected by flower petals. “We took these objective measurements of colors and then we plotted them subjectively into the way a bee sees them, to think about flower colors from a bee’s perspective,” Jones said. “Combining that with color learning hasn’t been done before.”

After making observations of pollinator behavior in the field, the students and Jones tested their ability to learn color in the lab by tempting them with either sucrose- and water-dipped paper strips of different colors.

This summer, and for summers to come, Jones is continuing this work with Kent Island students to better understand the complex dynamics of a pollinator-plant community. She hopes to one day be able to look at the totality of flower traits—their color, scent, size, amount of nectar, and nectar chemistry—and deduce how bees decide which blossoms to visit.

“The nice thing about this project in particular is it generates lots of data and a huge amount of questions,” Jones said. “I challenge each student to come up with their own question to ask.”

In addition to the pollinator publication, Jones is the senior author of another recently published paper on Leach's storm-petrels, “Adult survival in a small seabird, Hydrobates leucorhous, covaries with the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation over the past six decades.”

The small, endangered seabird nests each summer on Kent Island, in underground burrows. The paper's researchers took advantage of a multidecade dataset on the island's petrel population started in the 1950s by Charles Huntington (1919-2017), a Bowdoin biology professor and Kent Island director from 1953 to 1986.

“Long-term biological datasets are rare because of how labor- and resource-expensive they are to sustain, but they are critical to understanding the impact of global climate change on population demographics,” the paper explains.