Bowdoin Plans New Pollinator Gardens for Campus

By Rebecca Goldfine

A landscaping crew—with help from willing ecology students—will begin the process next fall of converting small patches of lawn into pollinator habitat. Once the gardens mature, they'll burst into a palette of colorful, nectar-rich blossoms every spring and summer.

The first area to be transformed is the strip of Coe Quad that runs along the brick wall of Studzinski Recital Hall. This past year, Sharon Ames, Bowdoin’s capital projects manager, consulted with campus stakeholders, including the biology department and Student Activities, about the future of the space following the removal of the Dudley Coe building.

“We need a lawn for food trucks and tabling activities, so the central portion is going to stay a lawn, but what should happen at the edge?” Ames said, recalling preliminary planning discussions. “We started to look at locations where we could add more texture and more color.”

With help from landscape architect STIMSON, Bowdoin has a plan—including a delightful hand-drawn map of flowers (shown above)—for a garden that will be “99.9 percent” filled with native plants. Cloutier's Landscaping, in Topsham, will do the construction.

The flowers and shrubs to be planted at the edges of Coe Quad will include a motley crew of natives, such as summersweet, buttonbush, columbine, serviceberry, Joy-Pye weed, and mountain mint. (The one plant not native to Maine, although native to North America, will be echinacea.)

The flowers and shrubs to be planted at the edges of Coe Quad will include a motley crew of natives, such as summersweet, buttonbush, columbine, serviceberry, Joy-Pye weed, and mountain mint. (The one plant not native to Maine, although native to North America, will be echinacea.)

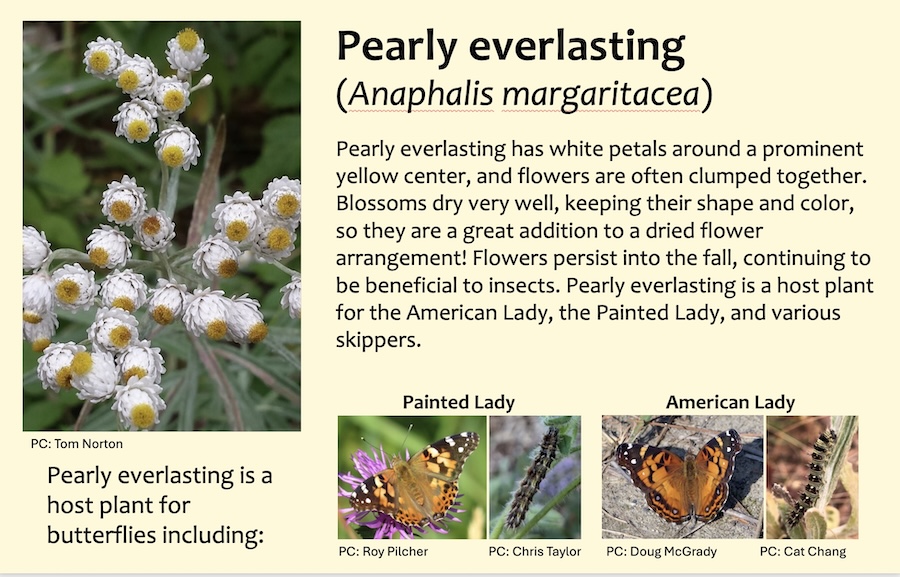

This spring, Ashwini Sahasrabudhe ’25 helped identify possible plants for the gardens and created a prototype for labels that could be included with the plants, like the one shown here.

“I am excited for some of Bowdoin's lawn to be changed into a more ecologically productive garden and to hopefully see it flourish over the next few years for the Bowdoin community and its ecosystem to enjoy!” she said.

Additionally, a small area near Moulton’s outdoor eating area will be turned into a native garden, with more outdoor seating.

“We’re calling them pocket seating areas, with smaller pathways that would have a bench or a table and chairs,” Ames said. “They’d be blended with some trees and some shrubbery.”

The new gardens will help support wasps, bees, butterflies, flies, beetles, and other insects that are lured to scented flower petals and sweet nectar. As the insects drink the sugary compound, they kickstart the life-sustaining process of pollination that fertilizes new seeds.

Assistant Professor of Biology Patricia Jones, an expert on pollination, said that once the gardens get established—which can take a couple of years, requiring patience from the gardener—she’ll bring her students by to identify bees and discuss bee ecology and diversity.

Though Jones lives with bees day in and day out in her Druckenmiller lab, on Kent Island where she does field research with students, and in her own backyard pollinator garden, a note of awe tends to enter her voice when she talks about bees and bee diversity.

There are 278 species of bees in Maine—including 270 native ones—with “many colors, stripes, patterns, and levels of fuzziness,” she said. “Which is as many breeding bird species as we have in the state.”

These include European honeybees, which, though introduced to the US, are critical for the pollination of many important agricultural crops; mining bees that live in underground holes; sweat bees who might sip the perspiration from your skin; cuckoo bees, which lay eggs in other bees’ nests; mason bees, and seventeen species of bumblebees.

Bumblebees and mason bees are buzz pollinators, meaning their small vibrating movements—producing that telltale sound of summer—help retrieve pollen from important native plants.

“Some crops, like blueberries, have to be buzz pollinated because their pollen is locked up in structures like a pepper shaker. And if they don’t get shaken, the pollen doesn’t come loose,” Jones said. Blueberry farms across Downeast Maine set out boxes of bumblebees in the spring to pollinate their fields.

While honeybees are generalists that will visit nonnative and native species alike, many native bees are more specialized. “They really need these native plants,” Jones said. “Some are specialized on just one or two species.”

“In this moment, where a lot of things feel hopeless climate change wise, all this data shows that re-wilding little bits of lawn does have an impact. And it’s something that is pleasurable, aesthetic, relaxing, therapeutic, and ecologically beneficial.”

—Patricia Jones, assistant professor of biology

In a time of “unprecedented insect decline” all around the world—due to habitat loss, pesticides, and parasitic infections—Jones said pollinator gardens offer a way to help. “The thing I think is exciting is that two percent of the United States is lawn, amounting to forty million acres, as large as all the national parkland,” she added. “We could turn that into bee habitat.”

Building pollinator gardens is “feasible, and lovely to live with while serving a bunch of ecological roles. The plants provide nectar to insects in spring, summer, and fall, seeds for birds in the winter, and food for caterpillars.”

The gardens at Bowdoin might even inspire more people to transform their grassy yards. “If we can carve out these kinds of places, my hope is that not just students, but also parents will like the aesthetic,” she said. “It’s a little bit wild, but you can have a different experience of being outside. You can imagine a parent saying, 'Why don’t we do this at home!'”