A Private Collection Burnishes the Bowdoin Museum of Art

By Rebecca GoldfineSince the Bowdoin College Museum of Art received 100 extraordinary objects from the Wyvern Collection as a long-term loan, the artworks have become "an integral part of the day-to-day life of the Museum," staff say. Because the Museum is so closely entwined with Bowdoin's academic program, the collection has also become a meaningful part of the College curriculum.

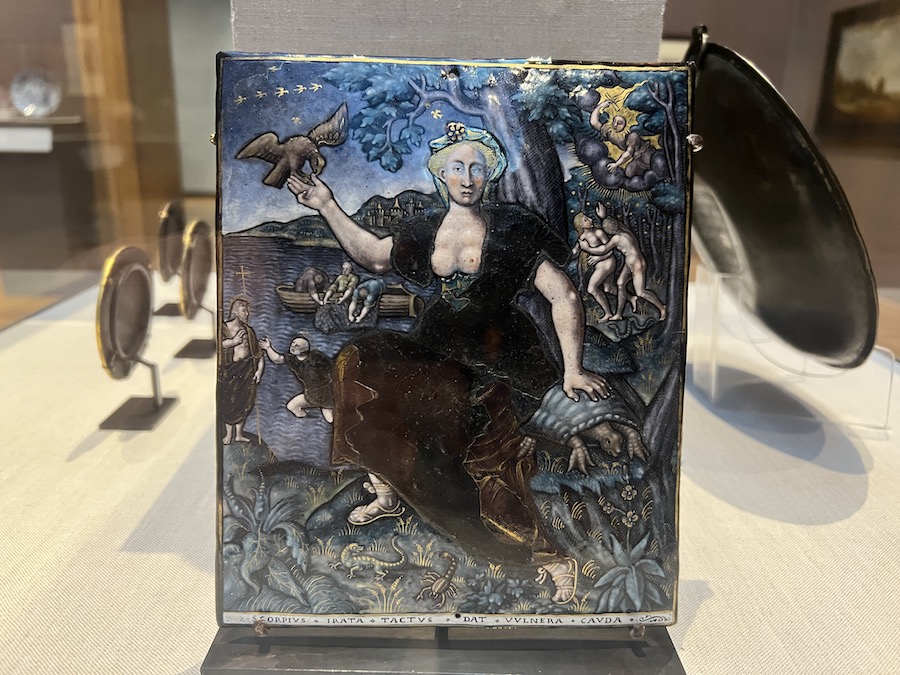

Medieval and Renaissance enamels from Limoges in the Bowdoin Gallery. They are part of the private Wyvern Collection on loan at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA). Museum Co-director Anne Collins Goodyear calls the collection "an extraordinary cultural resource."

In the center of the Bowdoin Gallery, which currently features selections from the Museum's permanent collection of European and American art, is a gleaming case of small, eye-catching medieval and Renaissance enamels drawn from the Wyvern Collection. Their vivid colors glisten under the museum lights, immediately drawing a visitor's attention.

The gallery's exhibition, "Re|Framing the Collection: New Considerations in European and American Art, 1475–1875,” explores the period leading up to and following the foundation of the College. The show questions and complicates the ways in which Europeans and their descendants viewed themselves and the territories they occupied in North America.

While the majority of enamels on view fall within the historical framework of the exhibition, some date to the late twelfth to early-thirteenth centuries, providing something of a prehistory for other objects in the exhibition.

Kate Gerry, a visiting assistant professor of art history, saw that a meaningful link could be made between the enamels and the themes covered by the show. She curated a small array of objects from the Wyvern Collection this summer, adding another layer to "Re|Framing the Collection."

"Those who reinstalled that room weren't thinking specifically about medieval art," Gerry acknowledged, "but the Wyvern pieces help to demonstrate the pre-American cultural context."

Early Americans brought with them ideas and norms from Europe, flavoring life in the colonies and young country. One of their predilections was for art or ornamental objects that depicted classical forms with biblical references, as the Wyvern objects demonstrate. "These are the ideas circulating in Europe about what is fashionable and how you decorate a domestic space, and you can see that playing out in America," Gerry said.

More expansively, the Middle Ages, which roughly span the years between 500 and 1500, "contained the seeds of many societal structures and cultural and scientific achievements that we consider so fundamental to our modern lives, although we may often overlook these important relationships between past and present," Gerry has written.

Since a donor in 2019 lent the Museum 100 objects from the extensive Wyvern Collection, one of the most important private collections in the world, particularly of medieval art, the Museum has broadened its scholarship and teaching, often in creative ways, such as with the current mini-exhibition of enamels.

In the past three years, the Museum has also—despite the pandemic—staged four other exhibitions with Wyvern objects. The largest was Gerry's major show, from August 2020 to February 2022, called "New Views of the Middle Ages: Highlights from the Wyvern Collection." Her students assisted with researching and writing labels, as well as contributed to the show's catalog. They also created online content to help the public access the works during and after the pandemic, long past the actual dates of the show.

Additionally, thirty-two classes have so far engaged with the objects from a range of disciplines: Africana studies, anthropology, art history, computer science, digital and computational studies, English, Francophone studies, history, and religion. (This refers to special visits faculty arrange with the Museum to show their students specific objects from the collections.)

Gerry said this type of intimate viewing "collapses the distance between art and viewer," and, as Bowdoin professor of art history Steve Perkinson has said, results in students "dwelling on specific pieces, noticing things that emerge slowly."

Often these visits spark student essays and projects. Gerry said she teaches with Wyvern objects in every class, and just this semester, ten students in her fall course Sacred: The Art of Devotion in the Middle Ages are writing papers about Wyvern objects.

Epic Travels and a "Global Middle Ages"

One of the most intriguing aspects of the medieval portion of the loaned collection (about three quarters of it) is that it includes works from Europe, Asia, and Africa. In response, faculty and students have been spurred to do research and teach on the important networks that linked the continents much more closely than many had long thought.

"The collection confounds our assumptions that medieval Europe was an insular place," Museum Curator Casey Braun said. She is especially excited by a couple of devotional objects from Ethiopia that reflect the rise of orthodox Christianity in the region, "challenging assumptions about African art and African belief systems."

Perkinson, a specialist in medieval and Renaissance art who helped select the loaned objects, said the transcontinental nature of the collection is "allowing us to convey to our students and museum visitors the ways in which current understandings of the history of art are changing."

He added, "The most recent scholarship is challenging old notions of artistic 'schools' or traditions that are defined along lines suggested by the boundaries of present-day nations (e.g., 'French painting' and so on). Instead we are able—again, in keeping with current trends in scholarship—to display the ways in which the different regions of the world have been interconnected over the course of millennia."

For these reasons and more, Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the Museum, said the long-term loan of the Wyvern objects, which not only represents a broad geographical reach but a vast stretch of time, "is one of the most important the Museum has ever had."

"The Wyvern collection highlights the Museum's commitment to opening up the Museum, to making it a site of research and exploration and the study of cultures and areas of the world that are far removed from our own," she said.

Faculty members and museum staff took advantage of the twenty-four African objects in the Wyvern Collection, which are mainly from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, to put together a unique show called "The Presence of the Past: Art from Central and Western Africa." Open from August 2020 to December 2021, the exhibition examined how the arts of Central and West Africa represent social themes across time. It was curated by David Gordon, Bowdoin's Roger Howell Jr. Professor of History, and Allison Martino, a former BCMA and Africana Studies postdoctoral fellow who is now a curator at the Eskenazi Museum of Art. They worked with students in Gordon's course Sacred Icons and Museum Pieces: The Powers of Central African Art. Female initiation mask made by a Mende artist from present-day Sierra Leone. Date unidentified. Height: 16 in. Wyvern Collection

Faculty members and museum staff took advantage of the twenty-four African objects in the Wyvern Collection, which are mainly from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, to put together a unique show called "The Presence of the Past: Art from Central and Western Africa." Open from August 2020 to December 2021, the exhibition examined how the arts of Central and West Africa represent social themes across time. It was curated by David Gordon, Bowdoin's Roger Howell Jr. Professor of History, and Allison Martino, a former BCMA and Africana Studies postdoctoral fellow who is now a curator at the Eskenazi Museum of Art. They worked with students in Gordon's course Sacred Icons and Museum Pieces: The Powers of Central African Art. Female initiation mask made by a Mende artist from present-day Sierra Leone. Date unidentified. Height: 16 in. Wyvern Collection

How the Wyvern Collection Came to Bowdoin

When the owners of the Wyvern Collection signaled their interest in lending art to Bowdoin's museum, Perkinson worked with museum co-directors Anne Collins Goodyear and Frank Goodyear and other faculty to select the 100 pieces now on loan.

"The loan fills significant gaps in our collection—European medieval art and African sculpture, for instance— both of which are crucial artistic traditions that had been rather sparsely represented in our holdings," Perkinson explained.

Their careful selection is likely the biggest reason the collection has been so popular with professors and students, Braun said. "This group of objects was selected very intentionally by faculty in different disciplines, so the collection we requested was aligned with research and teaching interests." She paused and then added another factor driving the high interest: "But they are also stunning objects."

While classes will continue to study the Wyvern objects in the semesters ahead, the Museum is also planning more public displays of them in its galleries, coinciding with talks and other programming.

"This infusion of medieval art transforms what we can teach and how we could teach it, and if it is here in the long term and people have the ability to plan, they can think about ways this could invigorate both art history and a broader medieval program here," Gerry said.

Perkinson agreed that the collection elevates the Museum and the college curriculum. "This material helps us further distinguish the BCMA from just about any other art museum in northern New England," he said. "There are other excellent collections in this area and in Maine, but none can display the products of human artistic creativity with the range that the BCMA can. Our collection has long been strong and deep, but this enhances that characteristic even further."

As the Museum's Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow, Sean Kramer assists many of the classes that incorporate museum art into their lessons.

As the Museum's Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow, Sean Kramer assists many of the classes that incorporate museum art into their lessons.

He shared an anecdote from a visit this semester by Professor of Art History Pamela Fletcher's class Becoming a Modern Artist: Matisse, Picasso, Valadon. Fletcher was teaching her students about the influence of African art on cubism, and to illustrate this, asked museum staff to bring out one of the very works that had impressed Pablo Picasso and George Braque, who actually owned the piece at one time.

"How often does that happen?" Kramer marveled. "You're talking about the legendary Picasso and Braque being inspired by African art and sculpture and then you can show the actual sculpture they were looking at?" Male power figure (nkisi) made by a Songye artist in present-day Democratic Republic of Congo. Date unidentified. Height: 13 7/16 in. Wyvern Collection